A major part of the strategy of Can't

Stop is when to stop

rolling. The point at

which one should stop depends on the three numbers marked and the

amount of progress

already made in the current turn (measured in fractions of the total

distance needed to

win a column). The ideal stopping point can be calculated from the

probability of a

successful roll, and the average progress value of a successful roll.

The ideal strategy

would consist of a table of 165 entries, one for each combination of

three numbers, each

entry showing the level of progress at which to stop for that

combination.

Such a table would, of course, be impractical to use in an actual game.

What we really

need is a rule of thumb that is simple to use and reasonably accurate.

The following rule,

called the Rule of 28, should prove helpful. Add the following values

for each number

marked or advanced in each column during the current turn (note that

each column counts

double when a marker is placed).

Column

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Spaces

3 5 7 9 11 13 9 7 5 3 1

Value

When Marked 12 10 8 6 4

2 4 6 8 10 12

Value

When Advanced 6 5 4 3 2

1 2 3 4 5 6

Note

that each column counts double when a

marker is placed. Add two points if all three columns marked are odd;

subtract two points

if all three columns are even. Add four points if all three columns are

less than eight,

or if all three are greater than six. When the total for the current

turn reaches 28 or

more, stop rolling (but do not stop before all three markers are

placed).

A few turns of a sample game:

(1) 1-1-3-4 Mark 2 and 7. Neither has been marked this turn, so

count 12 plus 2, or

14.

1-1-4-6 Advance marker 2, mark

column 10. Add 6 and 8

for a total count of 28. This is the total at which to stop.

(2) 1-2-5-6 Mark and advance 7. Count 2 plus 1 for a total of 3.

1-1-3-6 Mark 2 and 9. Add 12 plus

6 for a total of

21. Continue.

1-5-5-6 Advance 7. The total is

now 22. Continue.

1-2-4-5 Advance 9. The total is

now 25. Continue.

1-3-3-5 Miss. Bad luck!

(3) 2-2-3-3 Mark and advance 5. Count 6 plus 3 for 9.

1-2-2-4 Mark 3 and 6. Add 10 plus 4 for

23, plus 4 (because

3, 5, and 6 are all less than 7) for 27. Roll once more.

2-4-6-6 Advance 6. Add 2 for a total of

29, and stop.

The Rule of 28 will tell you within one roll the correct point at which

to stop in 75

percent of all cases (and within two rolls in 92 percent of all cases).

This is a fairly

good result for a simple, practical rule. However, since you are

playing against

opponents, do not follow the rule slavishly. Use your judgment as to

where you stand in

the game when making decisions on when to stop. In particular, when you

are behind in the

game, or are close to winning a closely contested battle for a column,

it is a good idea

to take extra chances (thus you would continue to roll even when your

turn total exceeds

28).

Thanks to Robert Abbott for introducing me to this

excellent game, and for

calculating the table of success probabilities which led to this study.

Can't Stop was developed from an earlier Sid Sackson game, Sid Sackson's Solitaire Dice, which appeared in A Gamut Of Games. This was designed as a solitaire game, but can also be played competitively. This is also an interesting dice game, giving wide scope for players to exercise skill in choosing what combinations to try for and how to score each roll. Briefly described, the player rolls five dice, and divides the roll into two pairs and a single die. The scoresheet is labeled with the two-dice totals from 2 to 12, and the single die rolls 1 to 6. The two pair totals from each roll are tallied off on the 2 to 12 section, and the single die on the 1 to 6 section. The player continues rolling and scoring, but can mark off only three different numbers as singles. The game ends when he has marked off a number as a single eight times. He then scores for each two-dice total he has marked off more than five times: 100 points per extra 2 or 12, 70 for each extra 3 or 11, 60 for each extra 4 or 10, 50 for each extra 5 or 9, 40 for each extra 6 or 8, and 30 for each extra 7. He loses 200 points for each two-dice total he has used between one and four times. This game is an excellent one for a duplicate format because there are no rethrows.

A sample three-handed game of 'Duplicate

Solitaire' Dice (The three numbers under each player indicate the two

two-dice totals and the single die left over):

Roll

Alpha Beta

Gamma

22244

8 4 2 6 6 2

6 6 2

15566

10 12 1 11 11 1 10 7

6

11234

6 4 1 5 5

1 7 3 1

12344

8 4 2 5 5

4 7 6 1

13456

10 8 1 11 7 1 7

6 6

12456

8 6 4 11 6 1 10

7 1

11112

2 2 2 2 2

2 3 2 1

11236

9 2 2 9 2

2 9 3 1

12356

9 6 2 11 5 1

9 6 2

12256

8 7 1 7 7

2 7 3 6

23456

8 8 4 9 7 4

9 9 2

13666

12 9 1 12 9 1 9 7 6

14445

8 6 4 9 5 4 6 3 1

23446

9 6 4 9 6 4

out

14466

10 10 1 12 5 4 ---

11233

4 4 2 6 2

2

11234

7 2 2 7 2

2

23456

8 8 4 11 5 4

14566

12 6 4 11 7 4

11223

4 4 1 5 2 2

12346

8 4 4 9 6 1

22334

6 4 4 5 5 4

Alpha scored 360 for his 4's, 6's, and 8's, but took 1000 points in penalties (2's, 7's, 9's, 10's, and 12's) for -640. Beta played an excellent game, scoring 560 for his 2's, 5's, 6's, 7's, 9's, and 11's, and took only 200 points in penalties (12's) to finish +360 and win. Gamma was runner-up at -420 (180 for 6's, 7's and 9's, 600 penalty points for 2's, 8's and 10's).

Solitaire Dice has been published several times

commercially: as Choice/Einstein (1989, Hexagames), Extra! (2011,

Schmidt Spiele), Can't Stop Express (2017, Eagle-Gryphon Games; this had a terrible rule change which was later reversed)

Another version appeared in Games Magazine (Jan/Feb 1978) under the title Great Races. This was previously published in 1974 as part of The 6 Pack of Paper & Pencil Games (Gamut of Games), and later as Mother Road (2022, Eagle-Gryphon Games).

Ten Thousand

Games to Play

with Dice

One of the most popular groups of dice games are point-scoring

games in which players have the

option to end their turn at a given point, or risk the score

already achieved on the turn by throwing further. Perhaps the

best-known of these is the French game of Dix Mille (Ten Thousand), so

called because the object of the game is to score 10,000 points.

This is a folk game, spread

mostly by word of mouth, with many variants and many different

names. I originally learned the game as Sparkle,

under which name I wrote about it in WGR4 and WGR5.

It appears in relatively few games compendia, even those

devoted to dice games (see the Bibliography for some written

references). The appendix (Short Reviews of

Games in Print) to the 1969 edition of Sid Sackson's A Gamut of Games

lists a version by Parker Brothers under the name Five Thousand, a name

sometimes used in English-language sources for a version of the folk

game with a shorter goal of 5,000 points.

Scoring in Ten Thousand

1

= 100

points

1-1-1 = 1000

points 4-4-4 = 400 points

5

= 50

points

2-2-2 = 200

points 5-5-5 = 500 points

1-2-3-4-5-6 = 1500 points 3-3-3 =

300 points 6-6-6 = 600 points

Let's look at the basic rules, and some statistical

strategy,

before examining some commercial variants. Ten Thousand is played

with six dice. The dice

are rolled and various combinations of dice score (summarized

above): Every one

thrown scores 100 points; every five scores 50

points; every triplet scores 100 times the value of the number

thrown (222 = 200, 333 = 300, etc.) except that 111 =

1000; and the sequence 123456 scores 1500.

After each throw, a player may stop and score all of the points

accumulated on that turn (turn score) to her permanent score (game

score). Or she may roll any non-scoring dice again to

try to score more points; any throw with no scoring combinations

(zilch) ends the turn and wipes out her turn score, with nothing added

to her permanent

score on that turn. If all of the remaining

dice score, she may roll all six dice again and continue to add to her

score. The game

is usually played in rounds; when one player reaches 10,000 points,

every other player who has not rolled in that round gets one more

chance to pass the leader. This is a

very interesting game which can be

played solitaire or competitively, and which contains a

fair amount of skill. Here are a few sample turns:

Roll

Score Turn Score Total Score

Comments

124556

200

200 0

Must continue

rolling; rethrow 246.

124

100 300

35

50 350

5

50

400

Rethrow all six dice.

135666

750

1150 1150

Puts the score

well over 500. A good

place to end the turn.

233566

50 50

33455

100 150

124

100

250

1400 Let's stop again.

123566

150 150

2556

100

250

Let's try for more this time.

16

100

350

Take another chance.

6

0 0

1400 Oops -- not as

lucky this time.

Many variants of the game require a

minimum game score (typically 500) before a player is allowed to stop

voluntarily; some even require a minimum turn score on every turn

before a player is allowed to stop. I dislike both rules: the skill of the game

is in deciding when to stop;

anything which reduces the number of decisions increases the luck

factor. The minimum game score requirement also may put players

hopelessly ahead or behind (if one player gets 500 on the first turn,

and everyone else misses for two turns, she has such an advantage she

may

never be caught). An excellent variant rule is described by Peter

Arnold in The Book of Games

(under the game's original name, Dix

Mille): a player reduced to one die has two throws to score (and

a 500

point bonus for succeeding), increasing the chance of a rollover and

rewarding more aggressive play.

Technical Analysis -- Ten Thousand

[Originally published in WGR5]

From an analysis of the various dice

combinations, we can compile the following tables of

probabilities and scores:

Number

Number of

combinations

Total scores for each

of dice for each number of dice

thrown

number of combinations

left 6

5 4 3 2

1

6 5

4

3 2 1

6 1548 192 48

12 4

2 1714950 112800 24450

8700 600 150

5 7200

0 0 0 0

0 540000

0

0 0 0 0

4 11520 2040 0

0 0 0 1728000 153000

0

0 0 0

3 12132 2400 480

0 0 0 4369500 360000

36000 0

0 0

2 8928 1704 384

96 0

0 4701600 615000

87600 7200 0 0

1 3888 840 180

48 16 0 2329200

435000 65100 7200 1200

0

0 1440 600 204

60 16

4

0 0

0 0 0 0

Total 46656 7776 1296 216 36 6

For example, when throwing four

dice, 480 out of the 1296 possible throws will leave you with

three dice, and these 480 throws score a total of 720

points. These tables were used to derive a basic strategy, which

boils down to the question of what score is enough to stop

and take a profit on the turn (keeping in mind that continuing to roll

risks missing and losing your score for the turn).

The score with which you should stop depends on how many dice you are

about to throw. So our basic strategy will consist of a set of six

stopping numbers.

The stopping numbers for the general strategy (derived from

formulas balancing potential adding gain from

continuing against the risk of losing your total for the turn) are:

Number

of dice to throw 6

5 4

3 2 1

Score

on which to stop 10400 2950 850

250 150 150

For example, when you are left with four dice to throw, you

will throw again if your turn score is less than 850, and

stop if it is 850 or more.

Notice two important things about these numbers. First of all,

you will never throw one or two dice (except when required to

make an initial score of 500). By the time you reach one or two

dice, your turn score will always be at least 200 (four fives).

Also, you will probably never stop with six dice to

throw, and infrequently stop on five (a score a high as 2950

for a turn is very high, and the odds against ever reaching 10400 are

astronomical). You will stop on three dice only

when you throw 111, 333, 444, 555, or 666 on the first throw,

when you throw three sixes in two or three throws, or when you

have scored on all six dice (in one or more throws) and are on your

second (or more) cycle (you will throw six dice a second time on about

6.6 percent of your turns).

This strategy gives the best average score per turn, and is suitable

for use when playing solitaire or when playing competitively in

many situations. It requires patience,

however; you will stop after a single throw over 35 percent

of the time. There are two situations where this basic strategy

might be modified, however. The first is when you have not

scored the necessary 500 points on a turn to begin accumulating

points. Should you stop the moment you reach 500? The second

situation is in a competitive game when you are trailing by a wide

margin. How wide a margin requires a change in strategy?

Let's look at a few statistics

obtained from a combination of probablility calculations, plus a

computer program which played 100000 turns following

the basic strategy, and 100000 turns trying to score 500 points.

The approximate probablity of scoring 500

points in a turn is 46.7%. The

computer scored 500 or more points in 46718 out of

100000 turns. The total score in the 46718 scoring turns was

3,438,8150, an average of 736.08 points per success, or

343.88 points per overall turn. The computer scored in 86264 out

of

100000 turns when stopping according to the basic

stopping numbers, fairly close to the calculated probability

of 84.1%. The total score for

100000 turns was 41,942,700 (419.427 per turn).

The results of this Monte Carlo simulation paint a clear picture

of the risk you take if you decide to risk another throw after you

have scored your first 10 points. Since

slightly less than half of all turns needing a score of 500 are

successful, you do not risk much by

continuing to follow the stopping numbers on a

turn in which you have reached your initial 500 points. Naturally

this means you will stop if you have three or fewer dice

to roll, and you will essentially always roll five or six

dice. Perhaps you might wish to play it safe and stop on

four dice -- unless all or most of your opponents have scored their

first 500 points and you are willing to take a risk to try

and catch up. Strategy in situations where you

are way behind is extremely difficult to quantify, and this is

perhaps where the judgment of the player should take

over. There may even be situations where you want to roll one die

in attempt to close the gap between you

and the frontrunner. Ten Thousand can provide some exciting play

in a competitive game between a number of players.

Commercial

versions of Five or Ten Thousand

Ten Thousand is perhaps the most popular dice

game ever in commercial

adaptations: even Yacht does not appear in as many different

commercial versions (looking through flyers from Toy Fair and

elsewhere, I see versions called Bupkis, Bummer, Farkle, etc).

In

WGR8 we panned a variant called Fill or Bust! (Bowman, 1981); to my

surprise this reappeared in a very similar vein a few years ago as

Volle Lotte! from the German company Abacus, and unaccountably has

received some positive press. Many other versions

have appeared since under different names, many with gimmicks such as

jokers or special bonuses for reaching certain scoring totals

exactly. Some games add bonuses for three pairs or double triplets.

Bone Didley, n.d., Carjulin Corporation, Calgary

Cosmic Wimpout, designed by W. W. Swilling and the Boston Logical

Society, published 1984 by Cosmic Wimpout, $3.50 for basic set, up to

$16 for deluxe set in carrying pouch

Fill or Bust, inventor uncredited, published by

Bowman Enterprises, 1981, $4.95

Gold Train, designed by Jeffrey L. Strunk, published 1995 by Strunk

Games, $24

Greed$, published 1980 by the Great American Greed Company, distributed

1986 by Avalon Hill, $14.95 in tube

High Rollers, published 1992 by El Rancho Escondido Enterprises, $7.95

postpaid

Six Cubes, published 1994 by Fun and Games, $9.95 retail

Volle Lotte!, published 1994 by Abacus, about $12 as import

Zilch, published 1980 by Twinson Company, $6.50 from Miles Kimball gift

catalog

Cosmic Wimpout is the most

popular of the commercial Five Thousand

variants; it even has its own Internet newsgroup and several World Wide

Web pages devoted to the game. It is unusual in using only

five (special) dice instead of six -- it also has a joker and several

special rolls (e.g. the equivalent of 5-5-5-5-5 wins automatically,

while 1-1-1-1-1 loses automatically). I don't find it

an improvement on the standard Five Thousand myself -- there are too

many rules limiting players' actions.

For players of Cosmic Wimpout (does anyone know anything

concrete

about the origin of Cosmic Wimpout?) who wish

to adopt an analogous strategy, many of the above comments are

applicable. Two major differences are the use of only five dice and the

presence of a black die which contains a wild

card. This requires the use of separate stopping numbers for dice

totals with and without the wild card die

(W indicates dice totals with the wild card). Also, a total

of only 7 points is needed to begin

accumulating a score. Certain rules, such as the

Reroll Clause, have been disregarded, as they produce

extreme complications in the calculations. The

basic strategy for Cosmic Wimpout is (using the scoring table

where the basic score is 5):

Number

of dice 5

4W 4

3W 3

2W 2

1W 1

Stopping

number 390 110

80 35 20

15 10 15 5

Fill or Bust! adds chance cards

to Five Thousand, which adds a

great deal of luck, reduces the number of options the player has,

and makes many of the remaining decisions trivial -- the

little skill remaining is overwhelmed by the chance

element. It was republished in 1994 as Volle Lotte!

High Rollers uses a set of dice

in which every number (1-6) has

different colored pips on each die. The scoring system gives

extra value to a straight (1-2-3-4-5-6) in which the six numbers are

the same color or six different colors, but the dice were misdesigned

so that a six-colored straight is impossible! The dice

don't add much to the basic game of Five Thousand, but they can be used

to design highly interesting versions of Yacht, using four rolls per

turn instead of three, and adding color-based categories (e.g.

six-color throw) as well as number-based ones.

The standard version of Zilch

is essentially the same game as Five

Thousand, but the variant games add extra scoring throws (e.g. three

pairs or two triplets) and extend the goal to 10,000 or 15,000 points

-- this improves the game a bit by making the average throw (especially

of six dice) more valuable and encouraging longer turns.

There is also a version in which throws of less than six dice can be

combined with saved dice to increase the score. Greed$,

by Avalon Hill, uses specially marked dice but is

essentially a straightforward version of Five Thousand.

Six Cubes, a recent board game

version of Ten Thousand, uses four white

dice plus a red die and a green die. Rolling a six on the red die

(except as part of a scoring combination) ends your turn with no score;

a green six doubles your points for the entire turn. The board

has a 10,000 point track with three Incentive Squares: ending your turn

on one earns a 1000 point bonus. I like those, but not the

colored dice, which increase the luck factor of the game.

The nicest physical production of the game is Strunk Games' new version

Gold Train, which comes with a

train-shaped wooden scoreboard (similar

to a cribbage board) with a compartment to hold the dice and

pegs. Gold Train is another five-dice variant (though using

standard dice, unlike Cosmic Wimpout), adding bonuses for four and five

of a kind and four and five dice straights, plus a rule which rewards

aggressive play: a player who stops after surpassing the score of

another player may attempt a Train Robbery (essentially a free turn

with the points from the turn subtracted from the overtaken

player). There are also a few money bags on the

pegboard, similar to the Incentive Squares in Six Cubes.

Two rules in Gold Train I dislike are Train Wreck: a 500 point penalty

for a non-scoring throw with five dice, which encourages passive play,

and End of the Line: you must reach 10,000 points by exact count, which

adds too much luck to the finish of a close game.

Pig is one of the simplest games of the jeopardy (push your luck) dice games. A single die is used. The object is to reach a total score of 100. On each turn a player rolls the die, keeping a running total of the rolls, and may stop at any time and add the total for that turn to her permanent score. Throwing a 1 ends the turn and wipes out the total for the turn.

Liar's DiceLiar's (or Liar) Dice is a well-known dice game

which is described in detail in

various editions of Hoyle.

Shut The Box and Tric-Trac are two of several

names for a simple dice

game which can be played solitaire or competitively. It has

appeared commercially as Snake Eyes. In its most common form, it

consists of a box with markers numbered 1 through 9, which are flipped

over to indicate that they are out of play. Two dice are thrown, and

the player flips one or more numbers which add to the sum of the dice;

e.g. on a throw of 10 (i.e., 5-5 or 6-4 -- the individual dice do not

matter), combinations which can be flipped are 9&1, 8&2,

7&3, 6&4, 7&2&1, 6&3&1, 5&3&2,

5&4&1, or 4&3&2&1. The object is to flip as

many numbers as possible before throwing a total which cannot be

covered. A win is achieved by flipping all nine numbers.

Whenever

desired (usually when all numbers larger than 6 are flipped), one die

may be discarded for the rest of the game. A quick sample (*

throw of

one die):

Throw

6-1 6-2

5-2 6-4 4-4 1*

Flip

7 8

4,3 9,1 6,2 --

Left

98654321 9654321 96521 652

5 (5)

Several scoring systems are possible -- e.g., you may count how many

flippers are left or the total of their numbers. The chance of

winning

with best play is about 8 percent. A 1000-game trial

produced 85 wins,

leaving an average of 2.3 flippers, totalling 11.43 points.

The worst

score was 8 flippers left for a score of 43. The game is

occasionally

seen with more than 9 flippers. A ten-flipper game is

playable (6

percent chance of a win), but the eleven- (1 percent) and

twelve-flipper (1/2 percent) games are far too difficult to

win. I have played many games of a giant version with 8

dice and flippers numbered 1 to 30. More dice and flippers give more

scope for

skillful play.

The Simpsons "Don't Have A Cow" Dice

Game (Milton Bradley, 1990)

Most commercial games named for T.V. shows, movies,

musical groups, and

the like are simple race games or other games of chance, not intended

for serious (or even semi-serious) players. It was nice to see that

this neat little dice game, based on the popular animated T.V. program,

has some interesting strategic features. It's an easy game to

learn, and can be played as a family game: older players can help

younger players select their bets

carefully. Basically it is a betting game --

the player whose turn it is to roll selects one of eight pictures

(containing one or more of the Simpson family members), then decides

how many dice to roll to try to match the picture, and how many chips

to bet. If he is successful, he wins the same number of chips from the

bank; if not, he loses his bet to the bank. Each of the other players

bets either for or against the roller, winning or losing in the same

manner. But the most important point is that if the roller is

successful, he wins the chips from players who bet against him. This

makes betting against the roller more dangerous, and encourages the

roller to take greater chances to encourage players to bet against him.

Another important rule is that the game ends when the bank or any

player runs out of chips (the player with the most chips wins).

The roller has three main choices to make (as outlined above), and each

non-roller has two choices (how many chips to bet, and whether to bet

for or against). Several factors need to be considered when making

selections, including the number of chips each player has, and the

number of chips left in the bank. A player in the lead wants to try to

maintain her lead while bringing about the end of the game, while

trailing players want to prolong the game while attacking the leader.

When the leader is on roll, it will often be a good idea to bet for her to avoid giving her extra

chips; conversely, it may be wise to bet against a player in danger of

running out of chips, to keep him from running out.

In order to play well, it is useful to know what the probabilities of

each roll are. The table below gives the five essentially different

pictures, and the probability of achieving each picture with the

allowable numbers of dice, rounded to three decimal places.

Number

of People Number of Dice Thrown

in

Picture

1 2 3 4

5 6 7 8

1

.333 .556 .704

2

.194 .407 .584

3

.157 .363 .549

4

.036 .115 .224 .344 .463

5

.199 .423 .607 .740

Gemstones (Mayfair Games, 1987, $3)

Gemstones is a 'free' game given away with a reasonably priced package

of 5 polyhedral dice (4-, 8-, 10-, 12-, and 20-sided). In each

round

each player has five throws and must save exactly one die on each

throw; the object being to get the highest total of the five dice (plus

bonuses for pairs or better, straights, etc.). The strategy is

too

clear-cut; a better rule would be to take five throws, saving as many

or as few dice each round as desired, Yacht-style; dice thrown a

fifth time must be kept. This leaves more room for decision

making and

increases the chance of bonuses. The bonuses themselves are

too small, in comparison to both the main scores and the difficulty of

achieving them. For example, a 5-point bonus is given for

throwing five

1's on the first throw. This should happen once in 76800 throws, and

the 5-point bonus is small compared to an average score of slightly

over 41 points per round which can be achieved with a simple

strategy.

Worse yet, the bonuses which can be usefully pursued (pairs, all odd,

all even) will not help produce high scores. The answer may be to

greatly

increase the bonuses for pairs.

Basic strategy table for Gemstones

Keep a die

after a particular throw if its value is at least that shown on the

table. For example, keep the 10-sided die after the third throw if 8 or

higher is thrown.

Throw

Die

1 2 3 4

4 4 4 3 3

8 7 7 6 5

10 9 8 8 6

12 11 10 9 7

20 17 16 15 11

Uno Cubes

Don't

Go to Jail (Parker Brothers, 1991) (invented by Garrett J. Donner

and Michael Steer)

Dice Deck

The following table of dice probabilities may be useful in a

variety of dice games in which dice totals, rather than combinations,

are the important factor. John Scarne's book has similar tables

going up to five dice, but it contains two incorrect figures for four

dice totals.

Numbers of

Combinations Of Various Totals With Two To Six Normal Dice

(Numbers in

parentheses indicate the total number of combinations)

Two Dice (36) Three Dice (216) Four

(1296) Five (7776) Six (46656)

2, 12 1 3,

18 1 4,

24 1 5, 30

1 6, 36 1

3, 11 2 4,

17 3 5,

23 4 6, 29

5 7, 35 6

4, 10 3 5,

16 6 6,

22 10 7, 28

15 8, 34 21

5, 9 4 6,

15 10 7, 21

20 8, 27 35 9,

33 56

6, 8 5 7,

14 15 8, 20

35 9, 26 70 10,

32 126

7 6 8,

13 21 9, 19

56 10, 25 126 11, 31 252

9, 12 25 10, 18

80 11, 24 205 12, 30 456

10, 11 27 11, 17

104 12, 23 305 13, 29 756

12, 16 125 13, 22 420 14, 28

1161

13, 14 140 14, 21 540 15, 27

1666

15 146 15, 20 651 16, 26 2247

16, 19 735 17, 25 2856

17, 18 780 18, 24 3431

19, 23 3906

20, 22 4221

21 4332

Widely used in fantasy games like Dungeons &

Dragons, dice are now being widely manufactured with the following

numbers of sides: 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 20, 24, 30, and 60. Other numbers have been made but are much less common

(except for two sided dice, which are usually coins). Dice

with 4, 6, 8, 12, and 20 sides use the five Platonic solids

(tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and

icosahedron). Dice with a number of sides twice a prime can

be made by joining two pyramids with a regular polygonal base (10-sided

dice

use two pentagonal pyramids, sometimes offset by half a side to produce

kite-shaped faces).

Attaching a shallow square pyramid to each side of a cube produces a

24-sided die. Prime-numbered

dice can be made as long prisms, or by repeating numbers on a larger

die (a game which needs results from 1-5 could use an icosahedron with

each number repeated four times). Photos of many

different dice can be found on Wikimedia Commons.

The first game I saw with 12-sided

(dodecahedral) dice was a simple dice baseball game called Dodeca,

which used six special dice labeled with outcomes for various baseball

events (including three different dice to represent three levels of

hitting ability). The popular baseball simulation Strat-O-Matic,

which for years used a Split Card deck of 20 numbered cards to produce

fielding and other subsidiary results, switched over to 20-sided

icosahedral dice when they became widely available.

Although 100-sided dice have been made (e.g. Lou

Zocchi's Zocchihedron,

which resembles a golf ball with 100 tiny round sides), some sports and

fantasy games use a special pair of ten-sided dice, one die labelled by

tens (0-10-20-30-40-50-60-70-80-90) and the other

by ones (0-1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9) to produce a set of possible outcomes

from 0-99 (or 1-100 if 00/0 is read as 100).

Dice other than the standard 6-sided ones can be

used to create variants of well-known dice games. For example, craps

could be played with other pairs of dice. However, in order to keep the

odds of winning approximately 50-50, it is necessary to change the

numbers which win at once (7 and 11 in standard craps), lose at once

(2, 3, 12), and point numbers (4-6, 8-10). Interesting variants

of

Yacht, Five Thousand, and Solitaire Dice or Can't Stop could also be

played with dice other

than the standard ones. For example, 8-sided Solitaire Dice could

be played, allowing four instead of three single numbers to be used,

and using the following scoring values:

100

80 70 60 50 40 30 20

2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9

16

15 14 13 12 11 10

Chase -- invented by Tom Kruszewski (reviewed in WGR7, p23)

Duell -- Lakeside, 1976

Freez! -- Judith Lahore, Freez Games, 1993

Genius Attack -- Invicta

6-Dice -- invented by Jr. A.N. Verveen, 1988, Leiden, The Netherlands

10x10 board, 10 dice per side (2-handed), 6 dice per side

(4-handed)

Tonobeb -- invented by Bruce Hollock, published in Gameplay magazine,

1:1, Feb 1983

Moonstar -- invented by Alex Randolph, published 1981 by Avalon Hill

(based on the earlier Corona, published 1974 by Kosmos; later published

under other names)

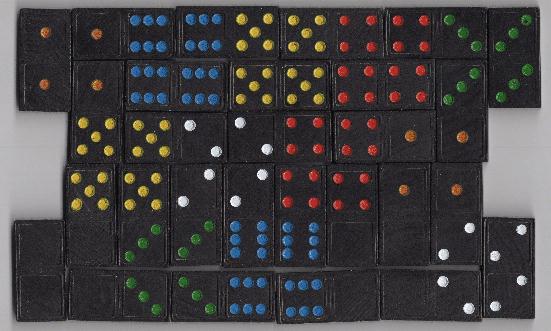

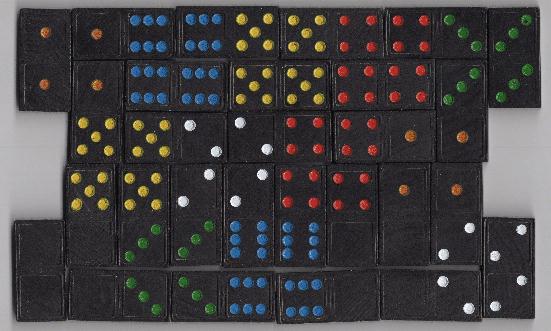

Domino Puzzles

Quadrilles -- Édouard Lucas

Multiplication Problems

This is a multiplication problem rendered in dominoes. So far I have not been able

to find a 5x5 solution.

The Mechanisms of Domino Games

There are hundreds of recorded variants of dominoes, most of which are folk games, so the rules (and names) vary somewhat from source to source. The majority of games are in the large family of block and draw games (including point games), where players start with a hand of tiles, and the main objective is to get rid of all of your tiles by matching ends to open ends on the board. A detailed taxonomy originally devised by Joe Celko can be found on John McLeod's Pagat website: this includes novel features of newly invented games which break away from the standard games. We summarize the main elements of traditional games here.Initial distribution of tiles

Most games are for two to four players, either

individually (round) or in two partnerships. The tiles are

placed face down on the table and mixed. Players initially

draw an equal number of tiles, depending on the game, with remaining

tiles, if any, forming a boneyard (equivalent to a stock in card

games). In block games, there is

no boneyard; either all of the tiles are distributed, or those not drawn are out of play for the whole deal.

Objective

The normal objective in the large family of block and draw games is to go out (play all your tiles before the opponents, also called going domino). In point games,

another objective is to score points by creating certain patterns on

the board (e.g. in Muggins/Fives, to make a play that makes the sum of

the free ends a multiple of 5, or in Bergen, to match two or more free

ends).

Initial Play

Usually the first play (e.g. Block or Fortress) is made by the

player holding the highest double; less often the tile with the largest

pip count (referred to as heaviest).

Some games instead draw for first play at the start (each player draws

one tile: the heaviest goes first, and the drawn tiles are returned and

remixed before players draw their initial tiles), and the first player

can start with any tile. In some games the largest double in the

set is

played (by anyone) before players select tiles. Play is

almost always in clockwise rotation (to the left).

Scoring

In the most common scoring system, the player who goes out first

scores the total of all the pips on the tiles still held by the

opponents. If all players are blocked, the player holding the

lightest hand (fewest total pips, or lighest individual tile in the

case of a tie) scores the total of all opponents minus their own

total. A game may be played to a target score, or for a fixed

number of deals (rounds).

See the description of All Fives and Bergen below, the two most common point games, in which points can be scored in play, as well as at the end of each deal.

Tricktaking Games

The tiles are divided into suits, with doubles belonging

to one suit and non-doubles belonging to two.

The

most popular is Texas 42, a four-handed partnership bidding game: this is a complex tricktaking game

in which 6-4 and 5-5 score ten points each; 5-0, 4-1, and 3-2 score

five points each, and each trick taken scores 1 point, for a total of

42 points per deal. See the Bibliography for several books

on the strategy of bidding and play.

Solitaires

Most domino solitaire games are adaptations

of card solitaires; packing is sometimes replaced by normal edge

matching.

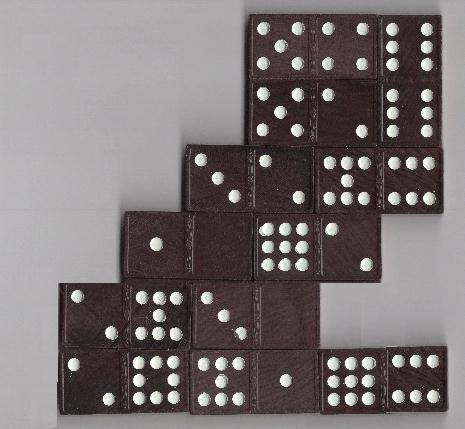

Summaries of the most common block and draw games

Block

Fortress

A simple block game (unrelated to the

well-known card solitaire) with

a double-six or double-nine set, and 3-6

players. In the three-handed (double-six) game, each player draws

9 tiles. The player with the 6-6 plays first, then draws the last

tile (so the boneyard is empty). Doubles are played

sideways, and are spinners: they can be matched on all four

sides, so there can be many free ends. A player who cannot play

passes. When a player

goes out, score as normal. Accounts of this game vary, and some

sources seem to confuse it with Sebastopol (at least one source gives Sebastopol and Fortress as alternate names for

the same game).

Maltese Cross

An elaboration of Sebastopol, in which the four ends branching from the

initial double must be matched with doubles on the next four plays,

after which play continues normally on the four ends.

Players who cannot play draw one tile, which they must play if

possible, or pass their turn otherwise.

Chicken Foot

Another game similar to Sebastopol, usually played with a double-nine

(or double-twelve) set, and played in a series of games in which the

first tile played is 9-9 in the first round, then decreases by 1 each

round, with the tenth round starting with 0-0. The intitial

double must be matched four times before any other plays are made (as

in Sebastopol). Players who cannot play draw one tiles and play

it or pass. Each subsequent double played to one of the

four lines must be matched three more times before any other plays are

made: first in the middle of the long edge, then twice at 45 degrees,

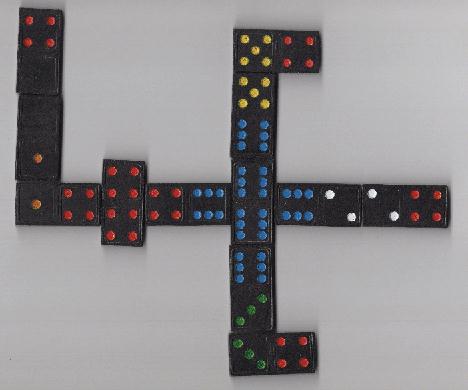

forming the shape that gives the game its name (picture above). Scoring is

negative, as in the card game Hearts: when a player goes out, they

score zero for that deal (unless they went out with a double, which is

a 50-point penalty), and each of the players scores the sum of the pips

on their remaining tiles (but 0-0 counts 50 points), and the lowest

score after ten rounds wins. Some sources credit Louis and

Betty Howsley with inventing Chicken Foot in 1986, but it seems to have

many variations.

International Dominoes

A four-handed partnership version of Block, one of the most popular

worldwide variants. It is played two against two with each player

drawing 7 tiles (so there is no boneyard). If any player

draws five or more doubles, they may call for a redeal (in some

versions, this is mandatory). Doubles are not spinners and

there are only two ends in play. A player who cannot play passes,

but you must play if possible. When a player goes out, their

partnership scores the total of both opponents' tiles, disregarding the

partner of the player who went out. If a deal is blocked,

the side with the lowest total scores the total of the opponents,

regardless of their own total. Most commonly the game is

played to 100 points. Rules for the first play vary: Anderson and

Varuzza specify that the first deal is always started by the player

with 6-6, who plays it. First play rotates to the left on

subsequent deals; the player playing first must start with a double if

possible. Lugo specifies that players draw to determine who

starts the first deal, and allows any domino to be played.

Pagat

gives a number of different variants (some regional variants gives

first play on each deal to the winner of the previous

deal). One set of international rules specifies drawing for

first play, and allow any tile to be played first.

The winning team in each deal scores all of the unplayed pips

(including the partner of a player who goes out), and the game is

played to 200 points.

In the version called Milo,

popular in Africa and Indonesia, the team winning each deal (by having

a player go out or by having the lowest total if the game is blocked)

scores one point, but if a player goes out and leaves both playable

ends with the same number (cf. Bergen below), their team scores two

points. First team to 5 points wins.

All Fives (Muggins, Five-Up, Fives, Sniff)

Another of the most popular games is

a scoring game, where any play which makes the sum of the playable ends

a multiple of 5 scores that many points for the player who played

it. See the books by Armanino and Palmer for more details and

strategy. Any tile can be played to start; the first double

played is a spinner, while subsequent doubles are not, so there are at

most four playable ends.

In Fives and Threes, popular in Great Britain, any total which is a multiple of 3 scores 1 point for each three (3 points for 9, 4 for 12, etc.) and the same for multiples of 5 (2 points for 10, 4 for 20); a total of 15 scores 8 points (5 for five 3's and 3 for three 5's).

Bergen

There are various rules for this, particularly in how the winner of a

blocked game is determined. It is played by two to four

players, drawing six tiles each (5 for four players). Play

starts with the lowest, not highest, double (or the lightest tile if no one has a double). Doubles are not spinners; there are only two free ends. A player who cannot play must draw until they can play, or until

the boneyard is reduced to two tiles (which can never be drawn). A play which makes both free ends show the same number (including the initial play of a double) is a doubleheader

and scores 2 points. Playing a double at either end of an

existing doubleheader, or matching a double at the other end, is a

tripleheader, and scores 3

points. Going out scores 2 points, as

does having the best hand in a blocked game (usually the lightest hand;

several sources have unnecessarily complex rules involving

doubles). Some sources only give 1 point for winning a

blocked hand; some also only give 1 for going out. Usually

played to 15 points for two players, or 10 points for three or

four. If you are 2 or 3 points from victory, you cannot win with

a doubleheader or tripleheader (they only count 1 point each if you are

two away, or 2 if you are three away, putting you 1 point shy in either

case).

Puremco (now The American Domino Company), in business since 1954, is one of the world's leading domino

manufacturers. They make a variety of sets up to double-18,

in many colors and styles, including personalized sets, plus cases,

playing boards for some of the more recent variant games, and other

accessories.

Cardinal Industries is a manufacturer of board, card, and dice games, including domino sets.

Dice Games

Arnold, Peter, editor -- The Book of Games, 1985, Exeter, 256 pp., ISBN

0-671-07732-5

Pages 79-80 cover Dix Mille.

Jacobs, Gil -- World's Best Dice Games, new edition, 1993, Hansen,

213 pp., paperback, no ISBN, $6.95

Pages 80-90 cover Five Thousand (Zilch or Farkle) and Ten

Thousand. This is a revised edition of Jacobs' 1981 book,

with a good bit of new material. Both editions contain

descriptions of some folk variants of Liars Dice (mostly simplified

versions, and none with the ingenious features

of Richard Borg's

game). The revised edition also contains rules for Dudo, a South

American folk version which probably gave rise to Perudo (which is also

mentioned briefly).

Mohr, Merilyn Simonds -- The Games Treasury,

1993, Chapters, 351 pp.[P],

ISBN 1-881527-23-9, $19.95

Pages 103-104 cover Farkle.

Scarne, John -- Scarne on Dice, Eighth Revised Edition, 1980, Crown,

496 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-517-541246, $14.95

The bulk of the book covers Craps and other gambling games. Yacht

and its Puerto Rican cousin Generala

are covered on pp.

364-368. Scarney's own invention Scarney Dice is covered in

Chapter 17 (pp. 370-394), followed inexplicably by three of his card

game inventions.

Scarne, John -- Scarney Dice, 1969, John Scarne Games, 84 pp.,

spiralbound

40 dice games designed for a special set of dice with the word dead

marked on two sides where 2 and 5 would normally be.

Vancura, Olaf -- Advantage Yahtzee, 2001, Huntington Press,

154 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-929712-04-8, $6.95

A computer analysis of Yahtzee, concluding that the average score with

optimal play is 254.6.

"Spots Before The Ice", Games & Puzzles 54, November 1976, pp.

14-15 (Dix Mille)

The Cosmic Wimpout page,

the company's official home page, includes various links, including an

FAQ.

Armanino, Dominic C. -- Dominoes : Popular Games, Rules, and Strategy,

1977, Simon and Schuster, 176 pp., hardback (1987, Fireside, paperback)

Survey of many standard games (including Five-Up, Seven Rock, Muggins,

and Bergen), plus a variety of blocking, round, and bidding

games. Reprinted in 1978 by Sterling (128pp., hardback), omitting

the chapter on bidding games.

Kelley, Jennifer A. -- Great Book of Domino Games, 1999, Sterling, 95 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-8069-4259-2, $6.95

Collection of games for two or more players, including modern

games like Mexican Train and Chickenfoot not found in older books.

Includes original games contributed by various inventors like David

Galt, some of which use special tiles added to the regular set.

There is also an assortment of solitaire games, and some games using

the 32-tile Chinese set.

King, Tom -- Popular Domino Games, n.d., Foulsham, 64pp., paperback

Rules for 19 common domino games. Bookseller lists give a

publication date of 1950, but that may be a reprint; the same author's book on patience was published in 1920.

Lankford, Mary D. -- Dominoes Around the World, 1998, 40pp., paperback, ISBN 0-688-14051-3

Lewis, Victor T. -- Domino Games, 1971, 1980, Puremco, 56pp., paperback

Rules for seventeen games, including matching/blocking games, bidding

games, and children's games, plus a brief history, a section on general

strategy, and a glossary.

Milton Bradley -- Dominoes, 1970, 2 pp. leaflet

Rules for five games, included with MB's Dragon Dominoes, one of the first double-12 sets.

Müller, Reiner F. -- Dominoes, Basic Rules & Variations, 1995,

Sterling, 95pp., ISBN 0-8069-3880-3 (translation of Spielend Domino

Lernen, 1987 [German])

Rules for about 19 standard domino games, plus puzzles, solitaires, and games for children.

Musante, Michael -- Pai Gow, Chinese Dominoes, 1981, GBC Press, 78pp., paperback, ISBN 0-89650-815-3

Description of a casino game played with the set of 32 Chinese dominoes.

Newsome, Travis -- Dominoes Game Night: 65 Classic Games to

Entertain and Excite, 2023, Black Dog & Leventhal, 259pp.,

hardback, ISBN 978-0-7624-8123-1, $23.00

An opening section on history and strategy, followed by a

wide-ranging survey of games divided into bidding, blocking, Asian,

scoring, and solitaire. Curiously spends 13 pages on games

played with a Cardomino set of 54 playing card dominoes, which could be

used to play virtually any card game.

Clarke, R.J. -- Domino Games, 50 Different Game Variations,

2016, Clarke, 109 pp., paperback, print on demand, ISBN 978-1530176151,

Rules for both well-known and (probably) original games, with very brief strategy notes, illustrated in black and white.

Perkins, Bill -- Dominoes Plus, 2001, iUniverse, 236pp., paperback, ISBN 0-595-20576-3, $14.95

Collection of over 100 games, mostly the author's own

inventions. Many games also use components from board

games, dice, and playing cards. The author prefers using a

set of dominoes with all of the non-doubles repeated (so a double-9 set

contains 100 tiles instead of 55).

Sackson, Sid -- A Gamut of Games, 1969, Castle Books, 1992, Dover, 210 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-486-27347-4, $6.95

See the Board Games Bibliography for more about the book as a whole. One of the original games by Sackson is The Domino Bead Game, inspired by Herman Hesse's Das Glasperlenspiel

(also known as Magister Ludi). This has a mechanism unlike any

traditional domino games, and was generally well-received by the

abstract game community. The book is still in print from

Dover.

Windham, Shane -- Table Games, 2013, Windham, 73 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-1475100785,

Domino Games (pp. 39-48) describes eight of the author's original games. No illustrations.

Puzzles (mostly)

Berndt, Frederick -- The Domino Book, 1974, Thomas Nelson, (Bantam, paperback), 195 pp.

Brief rules for 20 common games are given on pp. 7-36. Ten

solitaire games are described on pp. 37-51. The remainder of the

book covers puzzles, with solutions given for all.

Leeflang, K.W.H. -- Domino Games and Domino Puzzles, 1975, St.

Martin's, 162 pp., hardback (translation of Dominospelen en

Dominopuzzels, 1972 [Dutch])

The first 26 pages give rules for a dozen or so games and variants. The remainder of the book covers domino

construction puzzles. Some of the puzzles are magic

squares, others are arrangements of the double-six set so that

half-dominoes with the same number are all in groups of four, either in

a line, or in a square (the Quadrille puzzle named and studied by

Edouard Lucas).

Planet Dexter -- Dominoes, 1996, Scholastic, 48 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-590-97224-3

Children's book on domino activities, including a few games.

Strategy Guides for Individual Games

Badum, Jody, and Richard Hay -- Texas42: Zero to Hero, 2023,

Southpaws Playschool, 98 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-0-9978269-4-4, $9.95

Mack, Keith -- Texas 42 State Domino Game, Mack, 94 pp., paperback, ISBN 979-8-218-32902-0, $14.95

Roberson, Dennis -- Winning 42: Strategy & Lore of the National

Game of Texas, 5th edition, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2020, Texas Tech

University Press, 187pp., paperback, ISBN 978-1-68283-057-4, $18.95

Websites

McLeod, John -- Pagat

Huge collection of card games, including a page indexing rules for more than 150 domino games.

Spaans, Teun -- Domino Plaza

Long-running site with rules for many domino games and puzzles.

Portions of the section on Ten Thousand appeared in WGR4

(pp.8-9,

February 1985), WGR5

(pp.23-24, September

1985), WGR8 (p.35, July 1988), and WGR13 (pp.22-23, February

1998). The original version of the section on Can't Stop

appeared in WGR6 (pp. 33-34, September 1986).

Most recently edited on August 31, 2024.

This article is copyright

©2024 by Michael Keller. All rights reserved.