Backgammon -- Literature and Variants

compiled by Michael Keller

Thanks for assistance to Jerry Bailey.

The standard international game of backgammon is the most popular

version of a group of related games sometimes called Tables.

These games are remarkably consistent in being played on a board of 24

points, with 15 checkers per side. In a few older versions three dice

are thrown per turn instead of two. Usually the 15 checkers per

side begin off the board or piled up on a single starting point (one of

the mysteries of backgammon is how, where and when the starting

arrangement of today was developed). Movement also varies: in some versions players start in opposite corners and move in

the same direction. Another major difference is hitting of blots:

some variations do not allow landing on a point occupied by even one

enemy checker; others allow a single enemy checker on a point to be landed

on and pinned.

What is the essence of backgammon? What sets it apart from

Pachisi and other race games? I think that the answer lies

in the fact that a true backgammon variant needs a large number of checkers

on each side (at least a dozen) in order to carry out the sophisticated

blocking strategies which make backgammon so much more than a simple

race game. Another element of the better variants of

backgammon is that the sides move in opposite directions along what is

essentially a one-dimensional track, with one side entering where the

other side bears off. This leads to double-edged endgames of a

kind which don't occur in any other game I can think of; the best-known

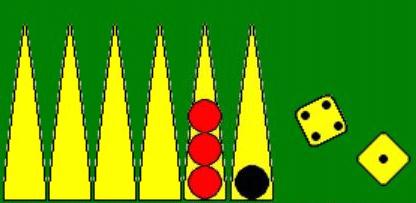

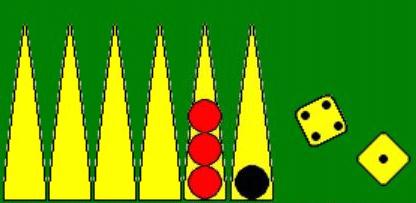

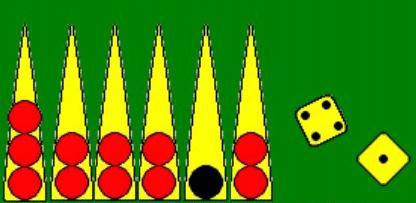

such position is Le coup classique,

with (say) Red, bearing off, having their last three checkers on

their two point, and Black with a lone checker on Black's one point --

depending on

what Red rolls next, the result can be anything from a Red backgammon

to a win by Black.

Le coup classique: Red is forced to leave two blots

Backgammon is the rare race game which transcends pure dice-rolling and

running. The doubling cube and the gambling element certainly

have added to its enormous popularity, but it is a superb game even

without them. Although it is a two-player game, the chouette

allows many players to participate (both the chouette and the doubling

cube are ideas which can be applied to other games). A

backgammon set requires a board, 15 pieces for each player, two dice

for each player, two dice cups, and a doubling cube (a cube whose sides

are marked with the numbers 2-4-8-16-32-64). A good backgammon

board should be just the right size for six pieces to fit comfortably

side by side on each half of the board, with a raised railing around

the outside and a raised bar dividing the board in half. Most

decent sets consist of a case which folds open to reveal the board, and

closes with a latch to hold the components when not in use.

The modern case with trays to hold borne-off pieces (and store them when not in use) was patented in 1935 by Arthur Popper. Cardboard folding boards (like those found on the backs of many dime

store checkerboards) are very poor for playing backgammon properly.

Modern Backgammon

The modern game of backgammon is actually a variant itself, based on the doubling cube.

This is a cube marked with numbers on each side (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64),

which starts each game in the middle of the bar, turned to 64 (which represents 1 when it is in the center). Either player may, before rolling, offer to double the point

value of the game by turning the cube to the next higher number and giving the cube to the opponent. The

opponent may resign the game at the current stake (drop) or accept (take) and take possession

of the cube, continuing play at the increased value. Once a game has been doubled, only the player who last accepted

(who is said to own the cube) can redouble. However, the game can be

doubled any number of times as long as the doubles are offered in

alternation. The doubling cube, as a device to keep track of the current stake, might have been invented by Grosvenor Nicholas, who wrote the first modern book on backgammon in 1928, or W. Whitewright Watson,

an early champion in 1925. The idea of doubling itself may

have come from older versions of the game, or from contract bridge.

A standard rule in tournament match play is the Crawford Rule:

when a player reaches a score one short of victory (e.g. 24 points in a

25-point match), the opponent cannot double in the next game,

This is sensible, as it gives the leader one game to close out a match

without the game being doubled (after that, the lead is essentially cut

in half, as the trailing player has no reason not to immediately double

in every remaining game).

The chouette, which originated with backgammon, is a method of turning

a two-player game into a multi-player game. One player

(said to be in the box) plays

against all of the remaining players, headed by a player called the

captain. The players on the team are ranked in an order (usually

initially selected by lot) which determines how soon they will become

captain. The captain has final say in the plays his team makes,

but his teammates are free to discuss the situation, offer suggestions,

and even try to talk the captain out of the move he has chosen.

The player in the box wins or loses one point for each player opposing

him (with the usual multipliers for doubles and gammons). If he

wins, he remains in the box, the captain moves to the bottom of the

team, and everyone else moves up in line (the player second in line

becoming captain). If the man in the box loses, the captain takes

over the box, and the loser moves to the bottom of the team as

before. The winner at the end of a series of games is the player

who is positive by the greatest number of points. Another way of playing with

multiple players is the non-consulting partnership, in which each side

of a two-player game is played by a team of two or more players, who

make moves in rotation without discussing the situation with their

teammates.

Backgammon was a well-known game long before the 20th century: Edmond

Hoyle himself wrote a short booklet on the game in 1744, and almost

every Hoyle up to the present

has a short section on backgammon. The doubling cube

helped spark a gigantic craze in the late 20's, peaking in 1930 (at least a dozen books were published that year alone), but

fizzling out a few years later. Nevertheless it was one of the

biggest game or puzzle fads of the 20th century, perhaps rivalled only

by the Canasta boom of 1950 and the Rubik's Cube craze of

1980. Backgammon came into vogue again in the late 1970's; this boom lasted

quite a bit longer, into the 1990's. Possibly the rise of

poker (especially Texas Hold'em) contributed to its decline, but it

never went completely out of fashion as it did in the

mid-1930's. The internet has sparked another surge in

recent years, with a new string of books on advanced strategy, helped by advanced computer analysis.

A Personal Viewpoint

I played very actively during the 1980's backgammon boom, and bought and

read every book I could get my hands on. Eventually the

emphasis on money, and several bad experiences, turned me away from

active play (I am not personally enthusiastic about

gambling). Frankly I am perfectly happy to play without the

doubling cube at all, although there is no question it adds a strategic

element to the game in matches.

Historical Variants (Tables)

Many early ancestors

of backgammon were closer to pure race games: they used three dice, and

started with all of the pieces off the board. See Salaamallah for accounts of many older variants.

Fayles is a three-dice

version with each player having 13 checkers already on their six point,

and the other two on the opponent's one point (perhaps the first

inkling of the modern setup). It had an unusual rule: a

player who could not play all three numbers rolled, lost

immediately. Other rules were as modern backgammon.

Trictrac is a very strange forerunner of backgammon, a complicated

game where hitting opposing pieces in particular ways, and making

certain patterns of pieces on the board, scores points. David Levy has a detailed account.

Regional Variants

In most regional variants, players roll one die to see who moves first,

but the winner rolls two dice again instead of playing the combined

roll, so playing a double on the first turn is possible, unlike

international backgammon. Both gammons and backgammons

count double (i.e. backgammons do not count triple).

In Iran (Takteh) and Turkey (Tavla), backgammon is played today by

rules very similar to the standard international game, with the

following exceptions: the player winning the opening roll does not play

the two numbers rolled, but instead rolls again, so doubles are

possible on the first move. A checker which hits in

its own home board cannot move again on the same roll (it can be

covered). When bearing off, pips cannot

be wasted unnecessarily: a checker which can be borne off directly

using the larger number cannot be moved forward with the smaller number

and then borne off; it must be borne off first and the smaller number

then played with another checker. There is no doubling cube, and backgammons count

the same as gammons.

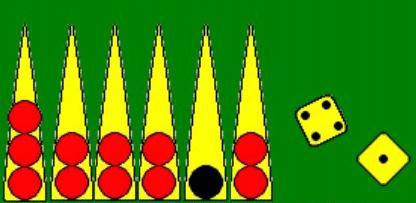

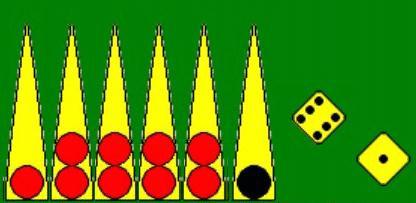

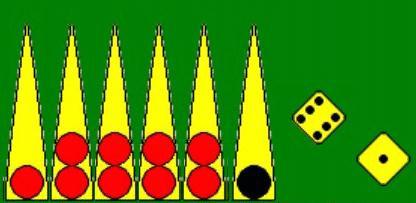

Tavla: Red cannot play

6-2*-1

Tavla: Red cannot play 6-5-off

Eureika

Bearing off practice for children. Each player starts with two

checkers each on their 6,5,4 points and three each on

3,2,1. A game of almost pure luck.

Blocking games

Moultezim (Fevga,

Gioul, Narde, Tawla 31, and Tawula are regional subvariants)

Each

player

starts with 15 checkers on one point, diagonally opposite.

Movement is anticlockwise: Black's first, second, third, and fourth

quadrants correspond to White's third, fourth, first, and second.

There is no hitting; a single checker (or more) on a point prevents the

opponent from landing there. As in regular backgammon, a

player may begin to bear off once all their checkers are in their home

quadrant. A short article by John Mamoun on Fevga is available on Internet Archive; his full-length book was published in 2018 and is in print.

Gioul is a variant of Moultezim

in which extra moves are given for doubles: a player throwing doubles

plays that number four times, then each higher number four times, as

long as possible. If a player cannot complete all the moves

up to 6-6-6-6, the opponent can play the remainder (as far as

possible), then take a normal turn. This obviously adds an

enormous amount of luck.

Jacquet

The first checker moved (courier) must reach your home board before all other pieces can move.

Pinning games

Plakoto (Mahbooseh, Tsilido, and Tapa are regional subvariants)

Each player starts with 15 checkers on one point. Movement is as

in backgammon (clockwise for one player, anticlockwise for the

other). There is no hitting, but a single checker on a

point can be landed on by the opponent, pinning it (more checkers of

the same color can also land on the pinned piece). The pinned

checker cannot move until the opponent moves all of the covering

checkers.

In Greece, matches (called Tavli) are played to a given number of points, consisting of three different games (Portes, Plakoto, and Fevga) played in succession, as many times as needed. Portes

is the Greek form of backgammon, played without a doubling cube and

counting double for gammon, but not triple for backgammon.

Players roll for first move, but the winner rolls again instead of

playing the combined throw.

Saitek used to manufacture a handheld backgammon computer which

played, in addition to the standard game, several alternate forms of

backgammon: Jacquet, Tric Trac,

and Moultezim.

Variants of the Modern Game

Positional variants

Acey-Deucy -- popular variant in the U.S. Navy. All pieces start

off the board and enter in the opponent's home board (any pieces can be

moved once entered, no matter how many are still off the board).

1-2 is a special roll which allows the player to play a normal 2-1, then play any number four times, then roll again.

Blast-off -- simplified variant invented by Oswald Jacoby and John R.

Crawford, and published in their book. The two checkers

usually on each player's 24 point are placed instead on their 13

point. Blots cannot be hit. It can help players learn

when to double (and accept) in running games.

Hypergammon -- a miniature form of backgammon with only three checkers

per player, starting on the 1,2,3 points in the opponent's home

board. It uses the doubling cube, but gammons and

backgammons count only in doubled games (Jacoby Rule). Hugh

Sconyers programmed a computer to play perfectly, by calculating the

equity value of every one of the more than 7 million possible

positions. Tom Keith's Backgammon Galore has a detailed study of the game.

Longgammon -- Each player begins with all 15 checkers on his 24 point.

Nackgammon -- Nack Ballard

modified the standard opening position, placing two checkers on each

player's 23 point (the opponent's 2 point), and removing a checker from

each player's 13 and 6 points. This is popular as a side event in

tournaments, usually played with no doubling cube and with no gammons

or backgammons counting.

Snake -- White starts in the normal position; Black has nine men on

the bar and two each on White's first three points. It was

designed as practice in playing (both sides of) back games.

Metavariants

Bazooki-Gammon -- Each player may call their dice roll once during each

game. Another popular side event (my source is the flyer for the

1991 Midwest Backgammon Championships) played without a doubling cube

or gammons.

Choose Roll vs. Double Roll -- a folk variation posted at least twice

on the Usenet group rec.games.backgammon. One player is allowed

to call any non-double dice roll every turn as their roll; the opponent

gets to roll and play normally (including doubles) twice per

turn. Kit Woolsey posted that the double rool player is

supposed to have a slight advantage.

Destructo -- (source: 2003 Boston Open flyer) Each player, once per game, may play the opponent's roll for them.

Duplicate -- adapted from contract bridge, and tried in both the 1930's

(see Nicholas and Vaughan) and again in the 1970's during the second

backgammon boom. It can be played two on two, or with a large

field of players, with every game being played with the same dice

rolls. Unfortunately, it does not appear to work well

(unlike bridge), as the positions diverge too quickly, so that the

throws have completely different effects in different games (it is

discussed in the book by Cooke and Orleans).

Exacto -- (source: 2003 Boston Open flyer)

Bearing off must be by exact count (e.g. you must throw a two or 1-1 to

bear off a checker from your 2 point). In addition, the

winner of the opening roll may reroll and play the new roll (including

doubles), and any player throwing doubles plays and rolls again (as in

Monopoly).

Misère -- like many games, backgammon (in most of its variants) can be

played to lose, even with doubling and gammon bonuses if you

prefer. It can be a long-winded game.

House Rules

Many people play that a point may contain a maximum of five

pieces. This doesn't effect the game much until the bearoff

phase. This is a standard rule in the Mexican variant of Acey-Deucy.

Turning a game of skill into a gambling game

A notable court case in 1982,

Oregon v. Barr, resulted in a ruling that "backgammon is a not a game

of chance but a game of skill". Ted Barr, a noted player

and writer, was arrested on gambling charges after running a

tournament. He called expert witnesses, including Paul Magriel,

and after four days, Judge Stephen Walker ruled in Barr's

favor. There is indeed a great deal of skill in backgammon,

both in checker play and doubling, but all of the optional rules below

heavily decrease the skill of the game and turn it into more of a

gambling game.

Automatic doubles -- if both players roll the same number when rolling

for first move, the doubling cube is turned to 2, but remains in the

center available to both players. This was a common house

rule in the earliest days of modern backgammon, but even early writers

like Nicholas and Hattersley disapproved, Hattersley correctly states

(p. 38 of How To Play The New Backgammon) "... this automatic double, unlike the optional double, detracts from the science of the game ...".

Beavers (and other animals) -- a

player who accepts a double may immediately redouble without giving up

the cube (the player who just doubled may resign the game at the

doubled stake). Even more extreme variants are raccoons

(immediate redouble by the first doubler) and higher redoubles with

varying names. Even more extreme is the Woodpecker.

Jacoby Rule -- gammons and

backgammons only count as single games if the cube is still at

1. Apparently almost universal in money games. It is not used in match play (e.g. tournaments). Supposedly introduced to speed up play, but a fatuous rule which reflects badly on the legendary games expert Oswald Jacoby.

(1) Why are you playing backgammon if it's boring? Even a long game is usually less than ten minutes.

(2) Back games are one of the most skillful aspects of backgammon, and often result in gammons and even backgammons.

Notable Computer Programs (currently available)

BGBlitz (Frank Berger, 1998)

Strong current program.

BKG 9.8 (Hans J. Berliner, 1979)

Early program by a well-known chess programmer. Won an

exhibition match 7-1 against Luigi Villa, who had won the World

Championship the previous day. (This was the first victory by any

game-playing program against a world champion.) Later analysis showed that Villa played better but had poorer dice rolls. BKG, however, made better cube decisions.

eXtreme Gammon (Xavier Dufaure de Citres, 2009)

As of 2012 this was rated as the strongest commercial program, in both checker and cube play.

GNU Backgammon (collective)

Jellyfish (Fredrik Dahl, 1995)

The first of the commercial NN programs (followed soon after by Snowie)

to be used by top players to evaluate positions and develop new

strategies. One of the first programs to use automated

rollouts to evalute different moves in a position.

Mloner (Harald Wittman, c. 1996)

Private NN program which was one of the top-ranked players on the First Internet Backgammon Server (FIBS).

Motif (Tom Keith)

Online program running in Java, which is not supported on present-day browsers.

MVP Backgammon (Justin Boyan, 1992)

Palamedes (Nikolaos Papahristou, 2024)

Freeware program which supports regional variants including Plakoto and

Fevga, as well as modern variants like Nackgammon and Hypergammon. Available for Windows and Android.

Silicon Highlands (Bob Landwehr)

Snowie (Olivier Egger and Johannes Levermann, 1997)

Another commercially released NN program with rollouts, among the strongest programs around the turn of the century.

TD-Gammon (Gerald Tesauro et al., 1992) -- the first backgammon program to use a neural network

(NN), playing 1-1/2 million games against itself to teach itself how to

play. It led to later NN programs Jellyfish and Snowie, all of

which helped to reveal new strategies for the game which were quickly

adopted by top human players. TD stands for Temporal Difference,

a machine learning technique, which was later used by the chess program

Deep Blue.

Commercial Variants

Four-handed variants with names like Quadro-Gammon and Multi-Gammon were published in 1931 during the backgammon boom. Similar designs appeared in the 1980's and 1990's, along with many other commercial variants.

Nannon -- Nannon Technology Corporation, 2004

A miniature form of backgammon with three checkers per side, played on

a board of only six points and one die per player. Still in

production, but the website is identified as not secure.

7-Sider Dice -- invented by Bernard Bereuter, bb Games Academy, 1992

These are among the most unusual dice in the world:

pentagonal prisms with seven sides. They are carefully designed

to have equal chances for all seven sides to come up. Bereuter

has designed several games using these dice. 7-Gammon is a backgammon

variant played on a 28-point board, with 17 men per side. The 7-sided

dice make it slightly harder to hit blots and easier to reenter from

the bar, rewarding aggressive play. [I have

experimented with a similar variant played with octahedral (8-sided)

dice and 20 men per side on a board 32 points long.]

Distant Relatives

Counterstrike -- Essex Games, 1978

Makhbusa

Marrakesh isn't really a backgammon variant,

but we mention it here since it uses the

bearing-off phase of backgammon as a mechanism.

Wykersham -- $38 from Land's End ?????

Bibliography

The literature of a game or puzzle enters an advanced stage of

development

when it progresses beyond general works, to books and articles on

specialized aspects of the game. For example, chess and checkers books

evolved from general manuals to detailed studies of openings, endgames,

middle game tactics, positional play, and the like. Bridge books

likewise progressed

to the study of particular types of bids (doubles, preemptive bids) and

card play (squeezes, opening leads). Backgammon entered

this stage with the publication of books devoted to openings, endgames,

back games,

doubling strategy, etc.

1. Standard Backgammon

Hoyle, Edmond -- A Short Treatise on the Game of Back-Gammon, 1753, Ewing, 47pp.

Probably the first book in English on backgammon as we know it today, though without doubling (Charles Cotton's 1674 The Compleat Gamester has about a page, with an odd scoring variant, and warnings about "false dice").

Older Books from the 1930's craze

"Bar Point" -- Backgammon Up to Date, 1931, De La Rue, 53 pp.

Bond, Ralph A. -- Beginner's Book of Modern Backgammon, 1930, Sears, New York, 95 pp., hardback

Readable online at HathiTrust. (The publisher J.H Sears is apparently unrelated to the co-founder of Sears and Roebuck.)

Hattersley, Lelia -- How To Play The New Backgammon, A New Revised Edition, 1930, Doubleday, 136 pp., hardback

Longacre, John -- Backgammon of Today, 1930, John C. Winston, 1973, Bell, 132 pp., hardback

Nicholas, Grosvenor, and C. Wheaton Vaughan -- Winning Backgammon, Problems and Answers, 1930, D. Appleton, 103 pp., hardback

Possibly the first-ever book of problems.

Thorne, Harold -- Backgammon Tactics, 1931, E.P. Dutton, 80 pp., hardback

Introductory Books

Ball, Baron Vernon -- Alpha Backgammon, 1980, William Morrow, 224 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-688-08714-0, $5.95

The author won the 1976 World Championship in the

Bahamas. The majority of the book is a reasonable strategy

guide. The last section attempts to show how you can win by

controlling the dice with your mind. Some reviewers took this seriously, others thought it ridiculous. Out of print and now rather pricey.

Becker, Bruce - Backgammon for Blood!, 1974, E.P. Dutton

Much derided, particularly in its recommendations for opening

moves. I share his disdain, however, for the Jacoby

Rule.

Bray, Chris -- Backgammon For Dummies, 2009, John Wiley & Sons, 259 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-0-470-77085-6, $14.99

Carter, Donald -- Backgammon: How To Play And Win, 1973, 1978, Holloway House, 247 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-87067-616-4, $2.00

Clay, Robin -- Backgammon, 1977, Teach Yourself, 164 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-340-22233-6, £1.75

Cooke,

Barclay, and Jon Bradshaw -- Backgammon : The Cruelest Game, 1974,

Random House, 210 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-394-73243-X[P], $5.95

Crane, Michael -- Teach Yourself Backgammon, 2006, Hodder, McGraw-Hill, 166pp., paperback, ISBN 0-07-148260-1, $10.95

New version of the Teach Yourself series, including some

positions analyzed by Snowie. Useful references, including

software and websites.

Genud, Lee -- Lee Genud's Backgammon Book, 1974, 1975, Cliff House (Price/Stern/Sloan), 158 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-8431-0342-6

Deyong, Lewis -- Playboy's Book of Backgammon, 1977, Playboy, 295 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-87223-522-X

Dor-El, David -- The Clermont Book of Backgammon, 1975, Winchester, 147 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-87691-307-9, $6.95

Goren,

Charles H., [Charles Papazian, Technical Consultant] -- Goren's Modern

Backgammon Complete, 1974, Cornerstone, 192 pp., paperback, $2.95

Heyken, Enno, and Martin Fischer -- The Backgammon Handbook, 1989, 1990, Crowood, 232 pp., ISBN 1-85223-402-4

Holland, Tim -- Backgammon for People Who Hate to Lose, 1977, David McKay, 153 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-679-50652-7

Jacoby, James Oswald, and Mary Zita Jacoby -- The New York Times Book

of Backgammon, 1973, Plume (Quadrangle), 175 pp., paperback, $2.95

Jacoby, Oswald, and John R. Crawford -- The Backgammon Book, 1970, Galahad Books (Viking), 224 pp., hardback, ISBN 670-14409-6

[Jacoby, Oswald, and John R. Crawford -- The Backgammon Book, 1970, Bantam, 244 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-533-13090-0, $2.95]

Kansil, Prince Djoli -- Backgammon!, 1974, Victoria, 80 pp., paperback

Lawrence, Michael S. -- Winning Backgammon, 1973, Pinnacle, 239 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-523-00860-4, $1.95

Obolensky, Prince Alexis, and Ted James -- Backgammon: The Action Game, 1969, Macmillan, 171 pp., hardback, $6.95

Reese, Terence, and Robert Brinig -- Backgammon: The Modern Game, 1976, Cornerstone, 141 pp., paperback, ISBN 346-12311-9, $2.95

Thompson, Dave -- Play Backgammon Tonight, 1976, Gambler's Book Club, 61 pp., paperback, ISBN 911996-58-3, $2.95

Tremaine, Jon -- The Amazing Book of Backgammon, 1996, Chartwell, 128 pp., hardback, ISBN 9780785805687

Woolsey, Kit, and Patti Beadles -- 52 Great Backgammon Tips, 2007, Batsford, 144 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-0-7134-9064-0, $12.95

Problem Collections

Cooke, Barclay -- Paradoxes and Probabilities: 168 Backgammon

Problems, November 1978, Random House, 184 pp., hardback, ISBN

0-394-50126-8, $8.95

A book whose reputation has suffered in the age of computerized

rollouts. Many of the solutions given by Cooke are now

regarded as wrong, some badly so.

Dwek, Joe -- Backgammon For Profit, 1975, 1978, Scarborough, 191 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-8128-2313-3, $4.95

Holland, Tim -- Better Backgammon, 1974, Reiss, 122pp., hardback, ISBN 0-679-50501-6

Collection of 64 problems and variations.

Kansil, Prince Joli -- The Backgammon Quiz Book, 1978, Playboy Press, 288 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-872-16491-8, $2.50

112 problems, each with three different rolls to play.

Robertie, Bill -- Advanced Backgammon, 1984, Robertie, 298 pp., paperback, $30

Robertie won the World Championship himself in between his first two books.

[short review in WGR4:]

Bill Robertie's second book on backgammon is a collection of problems.

What sets this book apart from earlier problem books is the depth of

the explanations of each problem, and the way in which the problems are

connected together with general discussions into a coherent whole,

which makes the book a textbook (in the mold of Paul Magriel's

Backgammon) rather than just a problem collection. Robertie gives

241 problems, divided into twelve categories, along with quite a few

tables and explanations of how to calculate various probabilities.

Problem 28 is particularly interesting. Next to a diagram of the

opening position, the problem reads "Black to play the opening roll."

Instead of forcing his own recommendations on the reader, Robertie

gives the results of a survey among 16 of the best players in the

world. But he didn't get the results by asking them -- he compiled them

from studying transcripts of actual tournament games played by each

player.

Robertie, Bill -- 501 Essential Backgammon Problems, 2000, Robertie, 376 pp., paperback, ISBN 1-58042-019-2, $19.95

Tzannes, Nicolaos S., and Basil Tzannes -- How Good Are You At

Backgammon?, 2001, Writers Club Press, 113 pp., paperback, ISBN

0-595-17462-9,

$9.95

50 problems covering all stages of the game, including doubling.

Woolsey, Kit, and Hal Heinrich -- New Ideas In Backgammon, 2000, Gammon Press, 336 pp., paperback, ISBN 1-880604-10-8

The first problem collection where the solutions are verified by

computerized rollouts. 104 problems are given, which the

authors also posed to a panel of 8 experts. Detailed explanations

of the best move in each position are given. The last

chapter gives statistics on the results of each move, as well as the

number of experts who chose each move.

Advanced Strategy

Ballard, Nack, and Paul Weaver -- Backgammon Openings, Book A;

2007, The Backgammon Press, 126 pp., hardback, ISBN 978-0-9797053-0-4

First of a projected series covering every roll(!). The first

volume covers the opening roll 3-1, with computer-backed

recommendations on how to play 3-1 on the first three rolls, and

general principles for later rolls.

Barr, Ted -- Barr on Backgammon, 1981, Writing Works, 202 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-916076-52-0

A collection of 90 columns from the author's regular feature in the Seattle Times.

Kleinman, Danny -- Vision Laughs At Counting with Advice to the

Dicelorn, 1980, Kleinman, 2 volumes, 438 pp. total, single sided,

paperback, $64

Kleinman, Danny -- Wonderful World of Backgammon, 1981, Kleinman, 132 pp., single sided, paperback, $18

Kleinman, Danny -- Meanwhile, Back At the Chouette, 1981, Kleinman, 142 pp., single sided, paperback, $20

Kleinman, Danny -- Double Sixes From The Bar, 1982, Kleinman, 135 pp., single sided, paperback, $19

Kleinman, Danny -- Is There Life After Backgammon?, 1983, Kleinman, 148 pp., single sided, paperback, $21

Kleinman, Danny -- How Can I Keep From Dancing?, 1983, Kleinman, 134 pp., single sided, paperback, $19

Kleinman, Danny -- The Dice Conquer All, 1984, Kleinman, 228 pp., spiral bound, $33

Kleinman, Danny -- How Little We Know About Backgammon, 1985, Kleinman, 168 pp., spiral bound, $25

Kleinman, Danny -- The Other Side of Midnight, 1986, Kleinman, 142 pp., spiral bound, $20

Kleinman, Danny -- But Only The Hogs Win Backgammons, 1991, Kleinman, 244 pp., spiral bound, $37

Kleinman, Danny -- A Backgammon Book For Gabriel, Kleinman, 1994, Larry Strommen, 144 pp., spiral bound

Kleinman, Danny -- Long Road to Gammon, Kleinman, 1995, 2003, 2007, Larry Strommen, 176 pp., spiral bound

Magriel, Paul -- Backgammon, 1976, Quadrangle (New York Times), 404 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-8129-0615-2

Still regarded by many as the definitive strategy guide.

Olsen Marc Brockmann -- Backgammon: From Basics to Badass, 2015, Olsen, 319 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-1512200447, $40

Trice, Walter -- Backgammon Boot Camp, 2004, Fortuitous Press, San Francisco, 339 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-943292-32-8, $40

Wachtel, Bob -- In the Game Until the End: Winning in Ace-Point Endgames, 1993, The Gammon Press, 103 pp., paperback, $25

Ward, Jeff -- Winning Is More Fun, 1982, Aquarian, 1988, Larry's Gammon Press, 164 pp., spiral bound

Ward, Jeff -- The Doubling Cube in Backgammon, Vol. I, 1982, Aquarian, 186 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-9609884-2-4, $24.95

Woolsey, Kit -- How To Play Tournament Backgammon, 1993, The Gammon Press, 50 pp., paperback, $20

Annotated Games

Cooke, Barclay, and René Orléan -- Championship Backgammon :

Learning Through Master Play, 1980, Prentice-Hall, 338 pp., hardback,

ISBN 0-13-126102-9, $19.95

Robertie, Bill -- Lee Genud vs. Joe Dwek: The 1981 World Championship of Backgammon, 1982, Robertie, 172 pp., paperback

Robertie, Bill -- Backgammon for Serious Players, 1997, 2003, Cardoza, 250 pp., paperback, ISBN 1-58042-077-X, $19.95

Five games played through and fully annotated.

Magazines

Backgammon Times

Chicago Point -- Bill Davis, ed., monthly, 6-12 pages, June 1988-January 2012 (236 issues)

The entire run of the magazine is available online.

Inside Backgammon -- Bill Robertie, 1991-1998

Leading Edge Backgammon -- Roy Friedman, 1991-1992?

Flint Area Backgammon News -- Carol Joy Cole, 1978-??

2. Historical and Regional Variants

Mamoun, Dr. John S. -- Plakoto Board Game Strategy. 2017, CreateSpace, 220 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-1976223761, $7.99

Mamoun, Dr. John S. -- Fevga or Moultezim Board Game Strategy. 2018,

CreateSpace, 334 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-1723972379, $12.99

Salaamallah the Corpulent -- Medieval Games, 1982, Third Edition, 1995, Jeff DeLuca, 203 pp., spiral-bound

Comprehensive survey of traditional board games, including a survey of

Tables, a family of games which was the forerunner of modern

backgammon. Two dozen variants are described, played with a

similar board and usually 15 checkers per side. At least one

variation uses three dice instead of two.

Schmittberger, Wayne -- New Rules For Classic Games

Chapter 11,

Beyond Backgammon, pp. 159-168, covers the doubling cube and chouettes,

then moves on to a few historical and regional variants.

Tzannes, Nicolaos, and Basil Tzannes -- Backgammon Games and

Strategies, 1977, A.S. Barnes, 267 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-498-01497-5,

$9.95

The first chapter describes standard backgammon (which the

authors have dubbed Hit). The next two chapters describe

Plakoto and Moultezim, which they declare to be much better and deeper

games than standard backgammon. They also describe the much

lighter variant Gioul.

Frantzis, Nicholas -- The Seven Popular Games of Backgammon, 1979, Exposition Press, 136pp., hardback, ISBN 0-682-49295-7

Out of print and rare. The author describes: standard

backgammon, Plakoto, a game of his own invention called the Never

Finishing Game (players may either hit or pin opposing single checkers:

a combination of backgammon and Plakoto), Gioul, Moultezim,

Acey-Deucey, and the Blocking Express game. [How can a game be popular before it is ever published?]

3. Modern Variants

Abak Evolution Backgammon is an

unusual modern variant (invented by Samy Garib) with five new classes

of checkers with special powers (Druid pins as in Plakoto, Guard can

only be captured by two men or another Guard, General can move

backward, etc.). The interactive website has a tutorial and

allows you to play online against computer or human opponents.

Greenacre, David -- American-Backgammon, The Game and Its Rules, 1990, 59pp., spiralbound, ISBN 0-9693690-X

Bizarre, complicated, and long-winded variant by an

inventor who admits he found the regular game boring. Many

rolls are excessively powerful; high luck factor. A new edition (83pp.) was

published in 1997, but the trademark

was not renewed and also expired in 1997. Copies exist in the Smithsonian Library and

the Library and Archives Canada. ISBN search comes up empty.

Molyneux, J. du. C. Vere -- Begin Backgammon, 1997, 1984, 2002, Elliot Right Way Books, 126 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-71602075-0

Chapter 10, The Tables' Family, describes Moultezim and

Ghioul. Chapter 11, Experiments on the Backgammon Board, describe

two variants designed by Matt Crispin:

(1) Tiles, where

dominoes are used to determine the rolls. The 21 non-zero

dominoes are distributed between the players, either randomly, or

according to a balanced formula. Each domino can be played once,

then the non doubles are exchanged between the two players (doubles are

out of play for the rest of the game once played).

(2) Grasshopper, a diceless abstract game only distantly related to backgammon. Details are in the book, which can be viewed online.

Websites

Tom Keith's Backgammon Galore is the best information site on backgammon, with many articles on the standard game, including an up-to-date tutorial on opening rolls, links to other pages, a detailed page on variants, and transcripts of older books from the 1930's.

The Gammon Press is one of the major backgammon publishers, owned

by two-time world champion and leading author Bill Robertie (also an

expert in chess and poker). They publish books by Robertie

and other authors, and from 1991-1998 published Inside Backgammon, one of two major magazines devoted to backgammon theory.

Most recently edited on September 9, 2024.

This article is copyright ©2024 by Michael Keller. All rights reserved.