Checkers and Draughts -- a

guide to variants and literature

compiled by Michael Keller

Thanks for assistance to Philip Cohen, Ed Gilbert, Jake Kacher, Ken Lovell, Bob Newell, and Dennis Pawlek.

Also particular thanks to Vashon Island Books, from whom I've purchased many of the older books in my collection.

Table of Contents

Definition

A Brief History

General Rules

Checkers vs. Chess

Anglo-American Checkers

Flying King (Queen) Variants

International Checkers

Frisian Draughts

Turkish Draughts (Dama)

Variants to Reduce Draws

Alternate Opening Positions

Modern Variants

Combinations of Chess and Checkers

Commercial Variants

Distant relatives of checkers

Notation and Diagrams

Software

Bibliography

Anglo-American Checkers

Introductory Works

History and Biography

Advanced Strategy

Endgames and Problems

Collections of Games

Openings

Go-as-you-please

The Two-Move Era

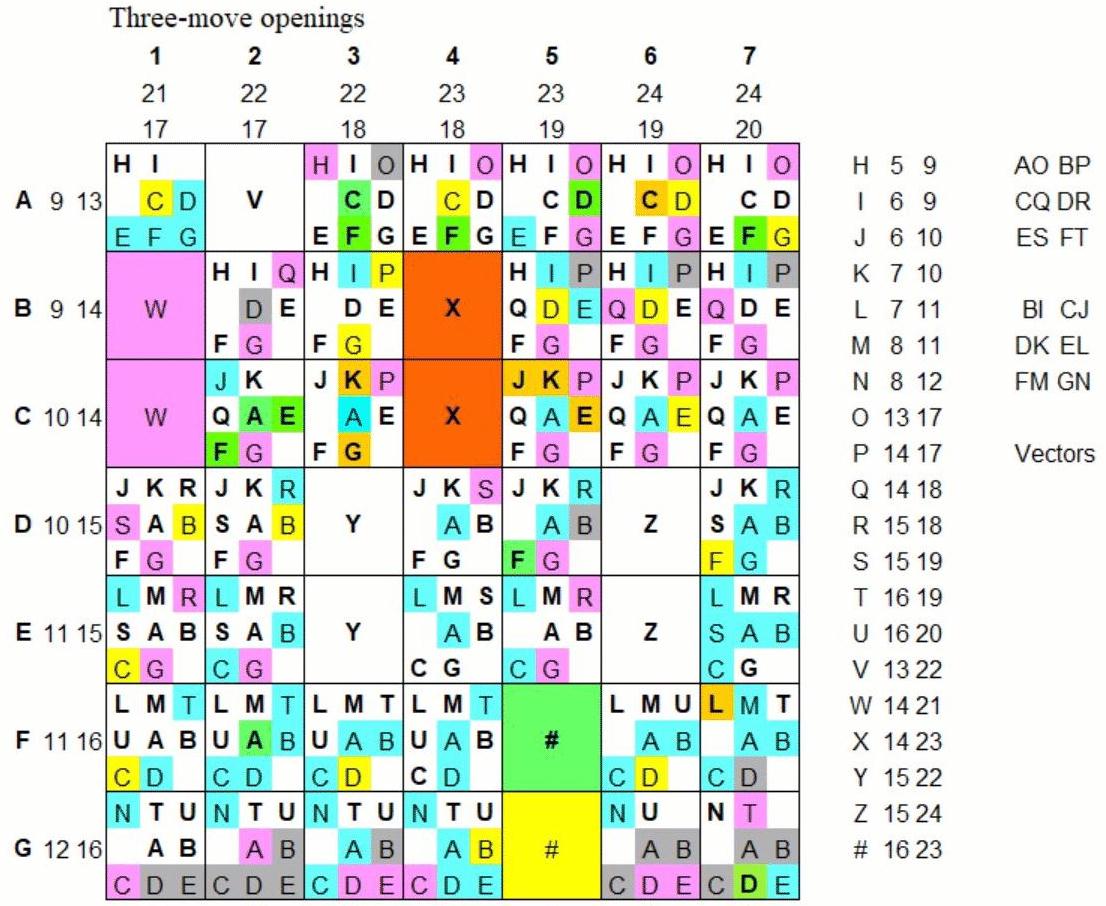

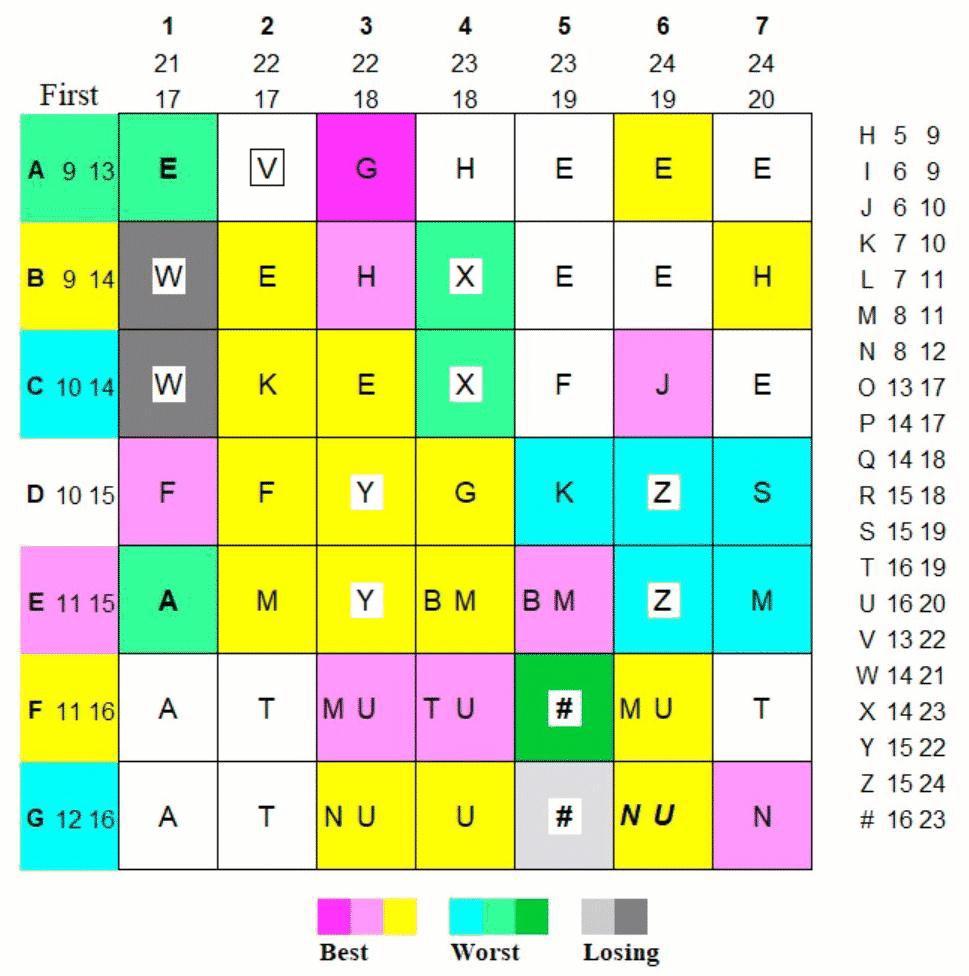

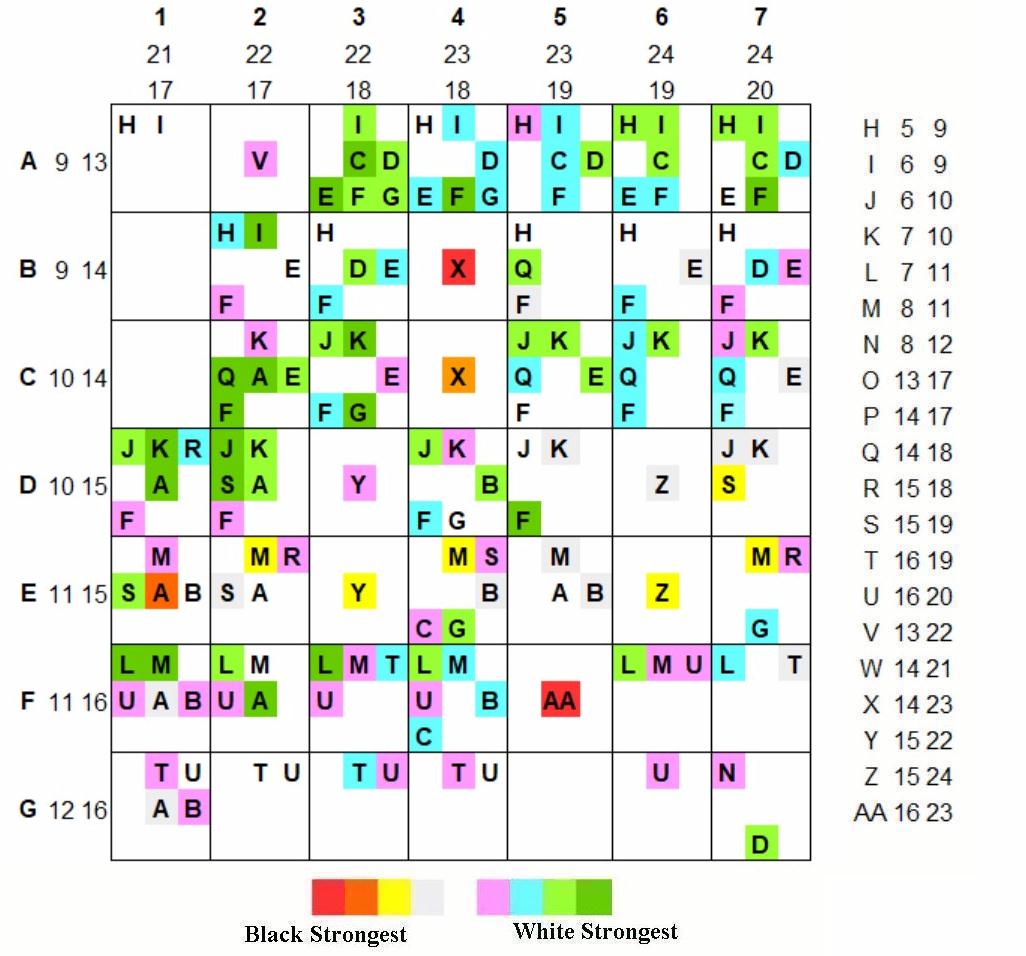

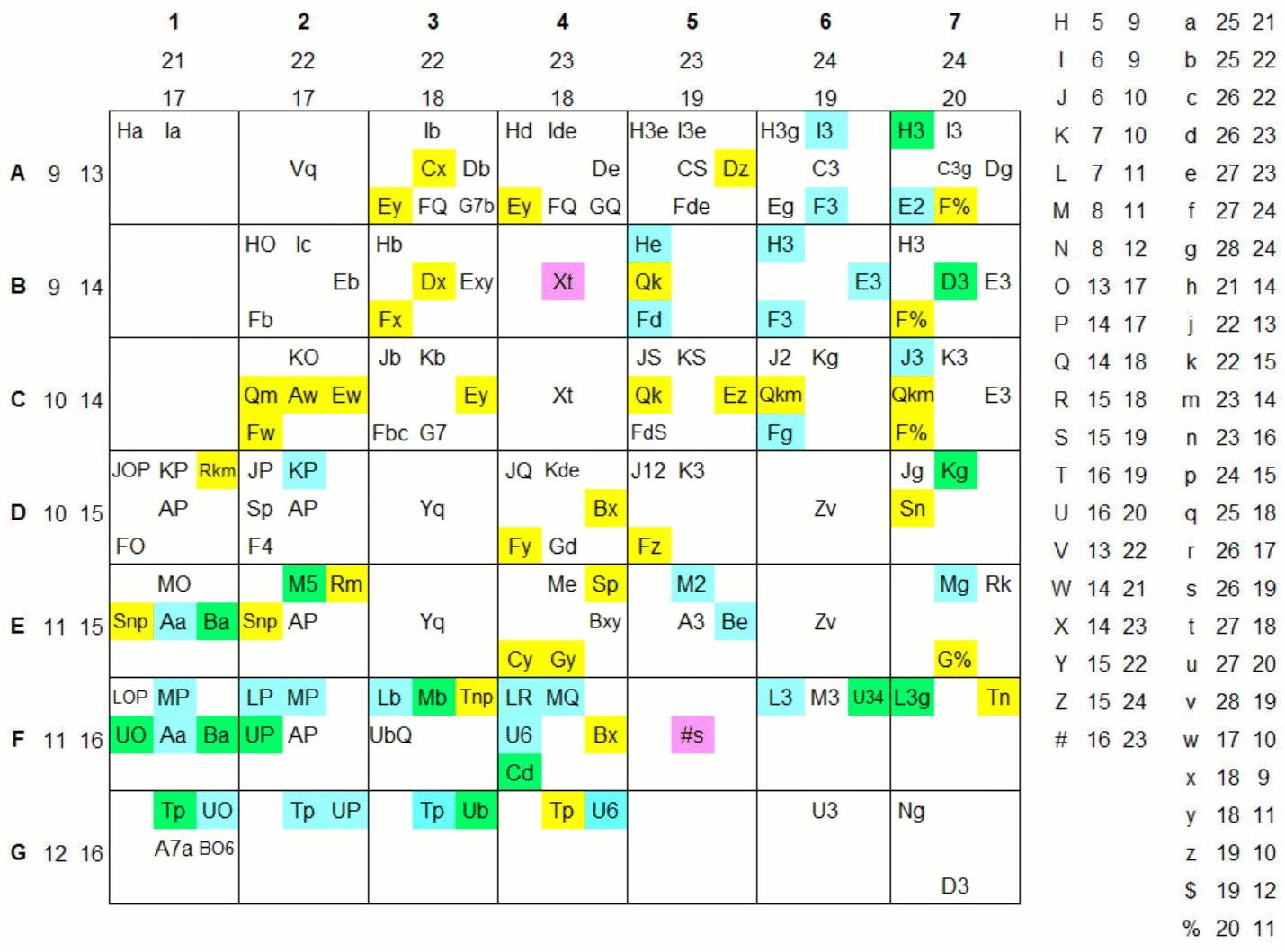

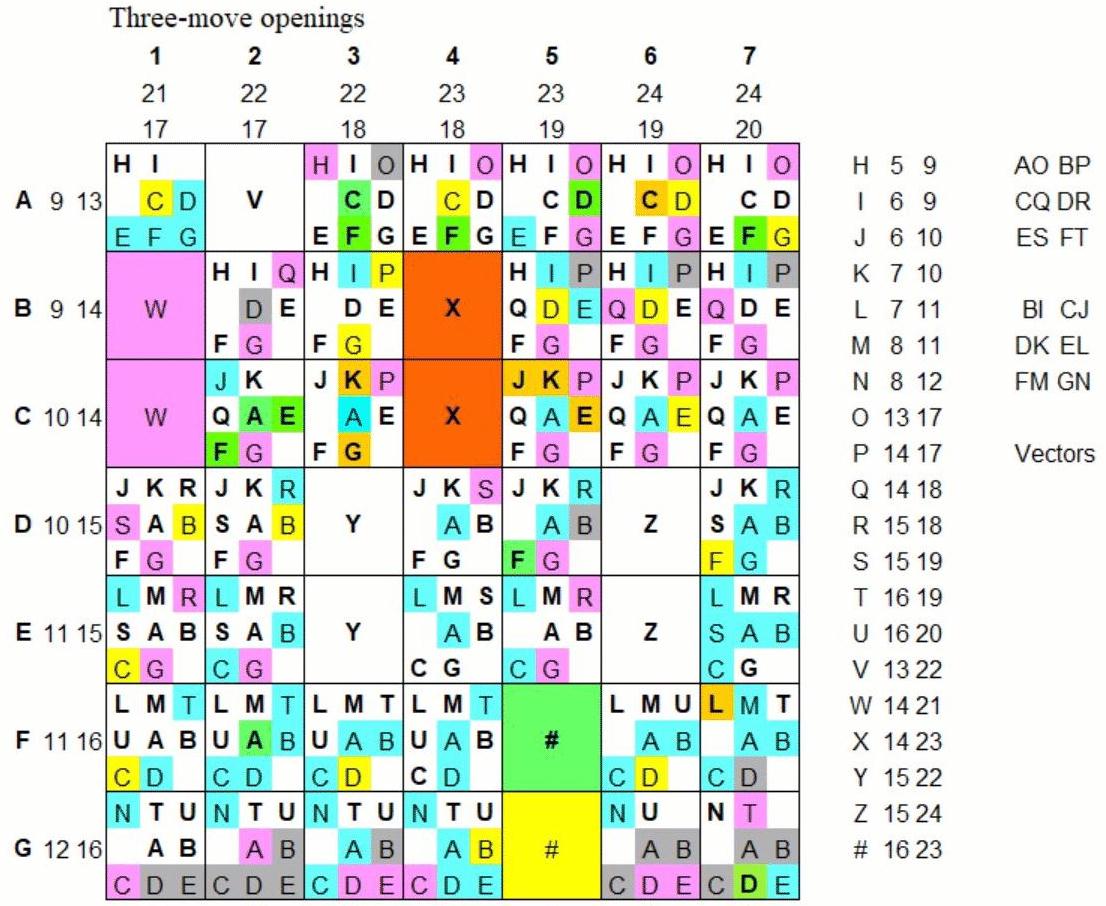

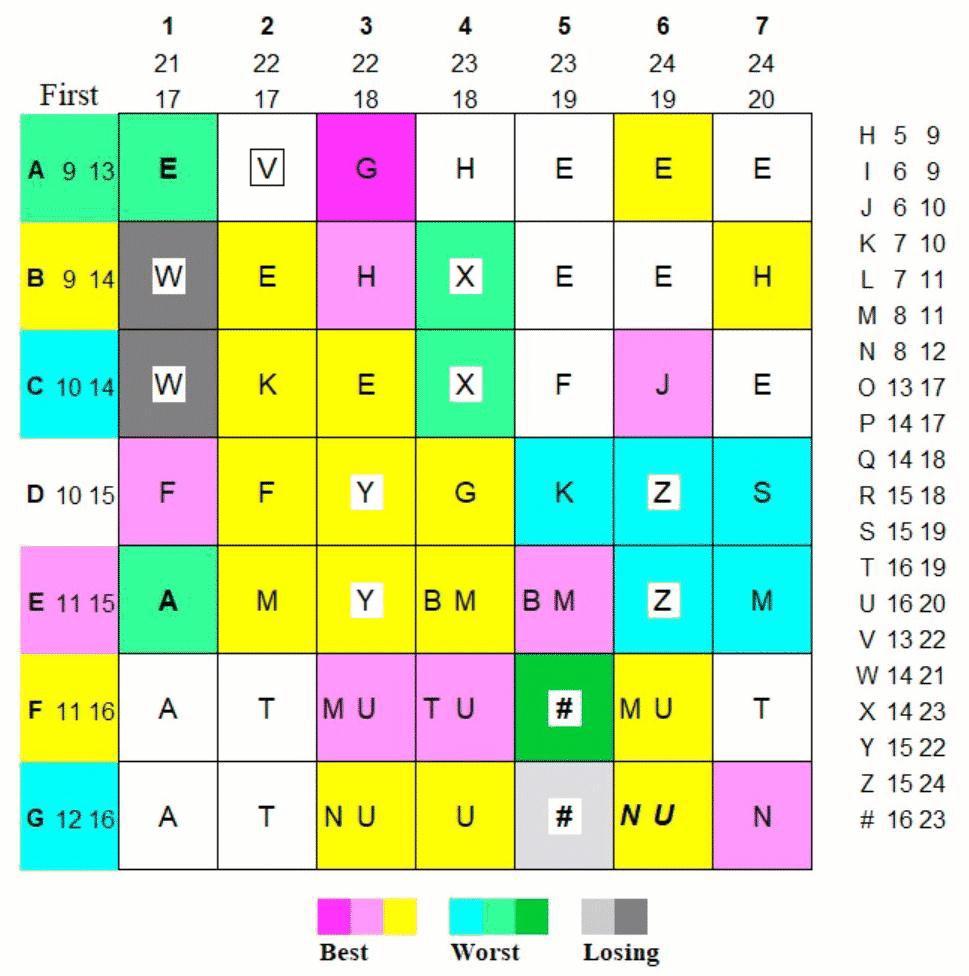

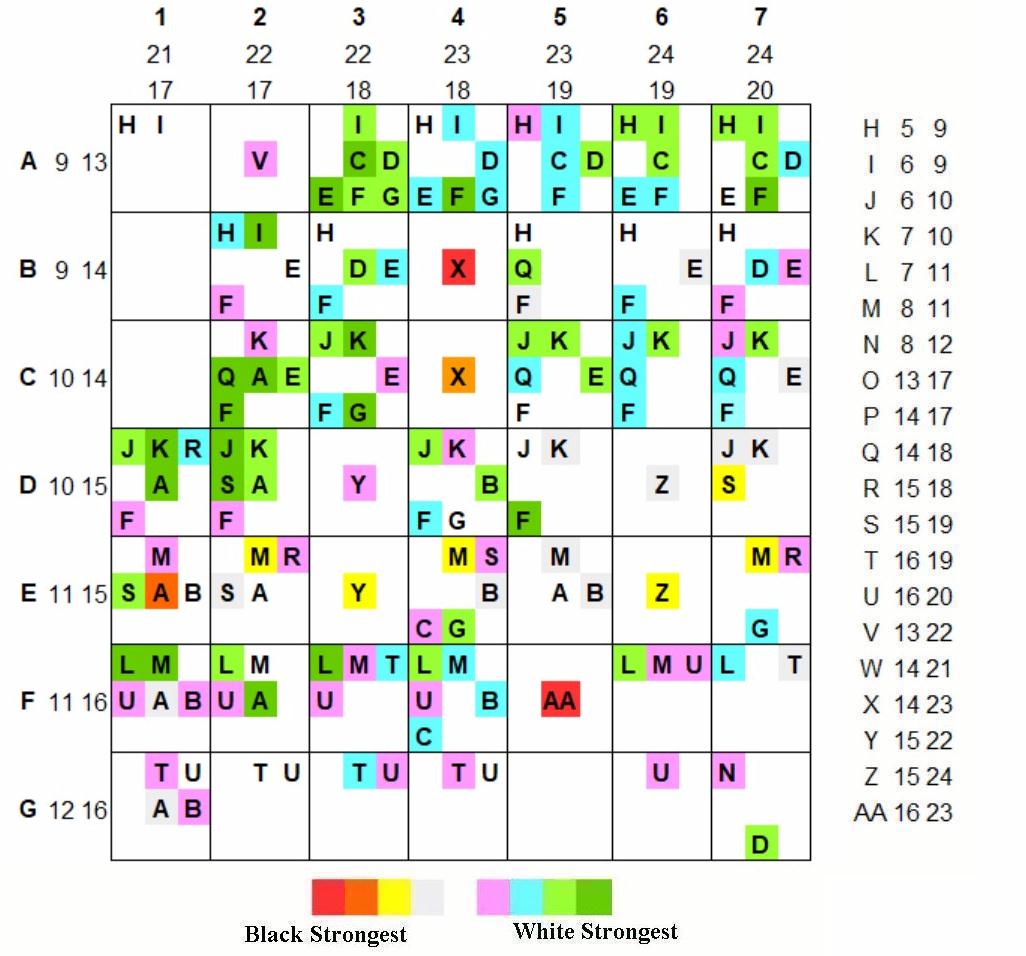

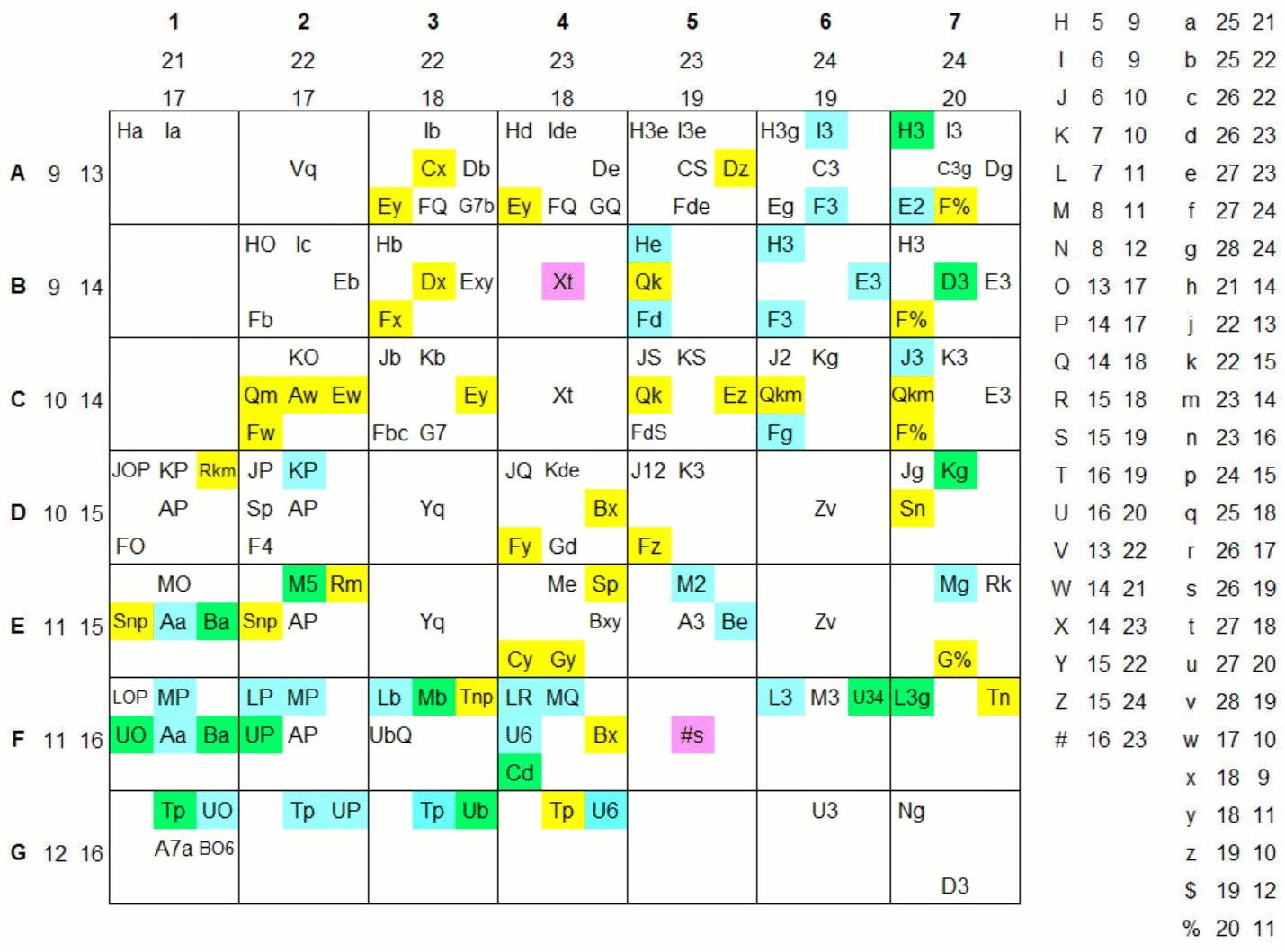

Three-Move Compilations

Modern Works

Individual Openings

Computers

Magazines and Newspapers

Other Variants

International Draughts (10x10)

Pool Checkers

Organizations

Websites

Appendix 1: Anglo-American (8x8) Checker Openings

Appendix 2: Historical Notes on Some Individual Openings

Appendix 3: Glossary

Checkers or Draughts is a family of abstract two-player board games in

which

capturing is done by jumping over opposing pieces to remove

them. It is played on a checkered square board usually

ranging from 8x8 to 12x12. Most variants of the game are

played on the dark squares only; each player starts out with a set of

identical pieces which fill the dark squares of the first three or four

ranks of their side of the board. The terms checkers (mostly used in the United

States and Canada) and draughts

(used in most of the rest of the English-speaking world) should be

considered interchangeable, like solitaire and patience. [Note

that when used as adjectives, the forms are usually singular: checker

and draught.]

A Brief History

Checkers as we know it today probably developed in 12th-century France or Spain, on a

chessboard, using the original form of chess queen called the fers,

which could only move one square diagonally. The

pieces were likely the same flat disks used in one of the tables games

(forerunner of backgammon). Possibly checkers was at least

inspired by the

ancient game of Alquerque, but the earliest forms of checkers only have

the jumping capture in common with Alquerque: pieces only move forward,

promote on reaching the last rank, and captures might not begin until

several moves have been made, since there are two empty rows separating

the opposing forces. The earliest form of draughts, as we know it

today, unlike Alquerque, did not not have forced captures, although virtually all modern

variants do: forced capture (jeu de force) was introduced in the 16th century. Variants with flying kings (queens

in French and Spanish)

probably developed soon after the chess queen and bishop adapted their

modern

unlimited move around 1475 (see the introduction to Westerveld's Draughts Dictionary).

At some point regular pieces also gained the power to capture (but not

to make regular moves) backwards, through backwards capture did not

take root in Germany, and neither flying kings nor backwards capture in

England.

The oldest book is supposed to have been published in 1547 by Antonio

de Torquemada; this is lost and is only known through references in

later books. Modern research suggests the book was actually written by Juan de Timoneda; a book on draughts was published under his name in 1635 which is likely the same book. Spanish draughts was already using flying kings (or long kings)

in the 17th century, and the three kings vs. one king ending, later

called Petrov's Triangle, appeared in Spanish books of the

period. In 1650, Juan Garcia Canalejas's book La gloriosa historia espańola del Juego de las Damas included one of the most famous opening traps, commonly named after him, but it actually appeared earlier in Pedro Ruiz Montero's 1591 Libro del juego de las damas vulgarmente nombrado el marro.

The game spread from France and Spain to the rest of Western Europe,

and also to Russia, where a slightly different version evolved.

A number of books were published in Germany

beginning in the 18th century; Russia produced a large amount of theory

and literature starting in the late 19th century, and Brazil did so

starting in the 1930's.

The European version expanded to a 10x10 board in the 18th century, and

in France and the Netherlands this became the standard version, with

the first world championship in 1885, and the World Draughts Federation

(FMJD) formed in 1947 by France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and

Switzerland. Known now as International Draughts, it has more

than 70 member countries.

William Payne's 1756 An Introduction to the Game of Draughts was the first book in English. Serious play began in Great Britain in the 19th century, and the first

recognized World Champion was Scotland's Andrew

Anderson in 1840. Books, newspaper columns, and eventually magazines began to

spread interest in the game. It also gained popularity in the

United States, which saw its first newspaper column on "checkers or

draughts", edited by I.D.J. Sweet, in the 1855 New York

Clipper.

By 1880, when H.D.

Lyman was assembling a book of checkers problems (which was published

in 1881), he drew from over 35

different American and British magazines and newspapers.

The English game also spread to Ireland and throughout the

English-speaking world, including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the Caribbean (especially Barbados).

In 1949, Arthur Samuel started programming the first checker-playing

program, building on earlier work by Claude Shannon (who proposed, but

never developed, an early idea for a chess-playing computer), and Christopher Strachey (who developed a draughts program for a video display in 1951 and presented his results at a conference in 1952). Samuel worked

out and tested various parameters

for evaluating checkers positions, discarding those that did not work

well. By 1952 Samuel had a working program for the IBM 701

computer, and by 1955 the program was one of the first successful

examples of machine learning (a term Samuel coined). He

pioneered some of the techniques of game programming (such as hashing, minimax,

and alpha-beta pruning), which influenced later programmers in various

games, including Gerald Tesauro's 1992 TD-Gammon and the chess program

Deep Blue, both also developed at IBM. Although Samuel's

Checkers Player never reached master strength, other

programs

followed in its wake. Tom Truscott and Eric Jensen wrote

the next strong program at Duke University. As personal

computers became widespread, other programs were developed with the

increasingly fast hardware becoming available. In 2003, Ed Trice

and Gil Dodgen published the first perfect

play database, with every

position up to 7 pieces in total, for their program World

Championship Checkers. In 2007, a team led by Canadian

computer scientist Jonathan Schaeffer

announced that their program Chinook

had established that 8x8 American

checkers (with unrestricted openings) was a draw with best play by both

sides (other variants, particularly the larger International game, are far from being solved).

General Rules

In most variants, pawns (plain

pieces, also called men or checkers) move one square diagonally forward, and can only capture by short leap,

jumping over an adjacent opposing piece to the vacant square

immediately

beyond. In some variants pawns can capture (but not make an

ordinary move) diagonally backwards as well as forward.

Pawns which reach the last rank (kingrow) are promoted to kings (gaining the power to move and capture

backwards in Anglo-American checkers), or in some variants queens (also called flying kings),

which can move any number of vacant squares in one diagonal direction. Queens or flying kings capture by long leap,

jumping over an opposing piece any distance away and landing any

distance beyond, provided all of the intervening squares (except the

square containing the piece to be captured) are vacant.

The object is to capture or block

all of the opposing pieces.

In almost every variant, captures are mandatory, and a capturing piece must continue to capture

if another capture is available from its landing square.

It is illegal to jump over a friendly piece, or to jump over an

opposing piece twice. In some variants, pieces are removed

as soon as they are captured (which may allow other captures);

others remove all captured pieces only at the end of a

move. Some variants require the maximum number of pieces to

be captured; others allow any piece which can capture to do so, not

necessarily one with the most available captures. In

most variants where pawns can capture backwards, a pawn which reaches

the kingrow by capture but makes another capture on the same move,

leaving the kingrow, is not promoted (Russian draughts is a notable exception).

At one

time, there was a rule called huffing:

if a player made a non-capturing

move when a capture was available, the opponent could remove a piece

which could have captured, then make a regular move (the opponent

could also let the move stand, or require the move to be retracted and

a capturing move played instead). This rule

was long ago abandoned in all

serious play, although it can still be found in beginners'

instructions and some general books on games (Cambodian and Malaysian draughts

seems to be the only regional variants that still use huffing).

There are many regional (national) variants, which may differ in

unimportant ways

such as which player goes first and whether the double corner is to

each player's left or right (the majority place the double corner on

each player's right, with a light square in the right corner as in

chess). In the early days of Scottish and English draughts, there

was not even a standard as to whether play was on dark squares or light

squares. For some reason, dark squares won out, despite

being worse from a visibility standpoint. Important

distinctions

in the regional variants are primarily in board size and capture

rules. We give the

most widely played variants below.

Checkers vs. Chess

Checkers has an undeserved reputation as a lightweight game for

children, and is used in fatuous metaphors comparing it unfavorably to

chess. Anecdotal evidence from discussion boards

suggests that a possible

reason so many people disparage checkers is that they are unaware of

the correct rules. Playing without mandatory captures is a

very

common house rule, and it is the way many people are taught to

play. But checkers

simply doesn't work without mandatory capturing:

the game is unwaveringly dull, and can easily turn into a completely

blocked position (especially when players refuse to move from their

back rank to prevent the opponent from getting a king). (At

least one online checkers app I found

had forced captures turned off by default, though it can be turned on).

Played properly, in any of its major variants, checkers is a deep

strategic game. Several books accurately refer to serious

play as scientific checkers. Many players who have mastered

chess and checkers (Newell Banks, Irving Chernev, Emanuel Lasker, Harry Nelson Pillsbury, Alexander

Kotov, Vassily Ivanchuk) hold both games

in high regard (even Bobby Fischer was interested in pool

checkers, and learned from the books by his friend Archie Waters). The

notable Russian chess magazine 64 for much of its history covered 8x8 Russian draughts, and later 10x10

International draughts. In Studying

Chess Made Easy, Andy Soltis suggests students play both games,

as checkers helps with visualization and calculation. Like

chess, checkers

has a long history of serious competition in several different forms,

including correspondence play, and a

voluminous literature (until sometime in the 20th century, its

literature was even larger than that of chess, according to Schaeffer's

One Jump Ahead). There

are also competitions in checkers played with faster time limits (e.g.

15 minutes per player per game in Rapid, 5 minutes in

Blitz). Checkers is well-suited to simultaneous

exhibitions, sometimes blindfold (checkers, particularly with flying

kings, might actually be harder to play blindfold than chess).

The noted chess historian Edward Winter has a fine article

on some of the notables who have played both games, including Banks (the subject of a separate article) and

Lasker.

Anglo-American Checkers

The

variant of the game most common in the United States (where it is

called checkers) and the United Kingdom (where it is called draughts)

probably has the largest literature of any form of the game (now second only to chess among board games). It is

played on the dark squares of an 8x8 checkered board, with each player

starting

with 12 men (generically pawns)

a side, on the

three ranks nearest them. The object is to capture or block

all of the opposing pieces. The player with the darker pieces moves first. Men move one square

diagonally forward, and capture

diagonally forward by jumping

over an adjacent opposing piece which has a vacant square behind

it. Captures are mandatory: a player must make a capturing move if one is

available, and must continue to capture with the moving piece if

another capture is available from the landing square (making a series of captures of the same turn). If more than one capturing

move is available (with more than one piece, or in more than one

direction), any capture (not necessarily the move that captures

the most pieces) may be played. At the end of a capture or

series of captures, all of the opposing pieces which were jumped are

removed. A man which reaches the last rank (the

opponent's first), by either a normal or capturing move, promotes to

become a king

(usually marked

by placing a second piece on top of it) and the turn ends.

A king moves and captures like a man, but in any direction (backward as well as

forward). It can also make multiple captures, jumping in

any direction on each jump. A player wins when their

opponent has no legal moves (usually because they have no pieces left,

but occasionally when all of their remaining pieces are

blocked). Draws occur when neither player can force a

win (usually due to equal material in the endgame). The game

with single step kings is also sometimes referred to as

straight checkers, to

distinguish from the larger family of games with flying

kings.

In most books, the first player is designated Black and the second White. Serious

players play with thick solid plain disks similar to backgammon pieces,

most often red and white, and a board of green and buff (white,

off-white, or cream)

squares. [Some

recent books designate the first player Red instead of Black, but we

will maintain the traditional terminology.] Play is on the green squares. Checker sets for children, at least in the United States, are usually

red and black plastic disks with ridges on both sides which allow the

pieces to lock together when a piece is kinged. These are dreadful, as black checkers show up poorly on black squares. Inexpensive

combination sets with 15 red and black checkers are often sold with a

folding board which has a backgammon board on the other side (and

sometimes a set of chess pieces as well). See notes below on diagrams.

Many checkers books dutifully include three or four pages on The

Standard Laws (originally compiled by Andrew Anderson in 1852), which

give intricate instructions on time limits, improper moves, etc., but

usually leave out trivial details such as how the pieces move and capture. A few works, such as Kear's Encyclopaedia, sensibly amend those laws to include the basic rules of play. W.T. Call's Vocabulary of Checkers cites an incident (No man to crown with) which

happened twice in 1884, where a player moved a man to the kingrow

before he had lost a piece, and refused to allow a checker to be

borrowed from another board (claiming a win), until the umpire

intervened. The laws as given today explicitly direct the referee to

furnish a checker in this circumstance.

Anglo-American checkers can played on

a 10x10 board: Zillions of

Games includes 10x10 implementations with both 15 and 20 pieces

per side (some online versions call these Sparse Checkers and Crowded

Checkers respectively). However, Martin Gardner's The Last Recreations notes that some endgames winnable on

the 8x8 board are draws on the 10x10 board (e.g. three kings vs two

kings in separate double corners: the corners are too far apart for the

three kings to threaten both simultaneously).

In recent years the game has spread beyond its traditional centers

in the English-speaking world, to countries such as Pakistan,

Turkemenistan, the Ukraine, and Italy (as noted below).

Italian Checkers

A variant of Anglo-American checkers, in which kings cannot be

captured by pawns. The board is rotated so that the double corner is to each player's left. The rules for multiple

captures are complicated: if multiple captures are available with

different pieces, the largest number of pieces must be captured; if

equal, capture by a king must be chosen over capture by a pawn; if

two kings can capture equal numbers, the one which captures more kings

must be chosen; if equal, the one which captures a king

earlier. Some sources say a player who loses without a

pawn being promoted loses double; this does not seem to be part of the official rules. Ed Gilbert's Kingsrow checkers program has a

version for Italian Checkers.

The Italian game is similar enough to Anglo-American checkers that

several Italian players have won the world championship in the latter,

in both three-move and go-as-you-please formats.

Flying King (Queen) variants

[Variants in which kings

(queens) move and capture any distance along an open diagonal.]

International Draughts

The most popular form of the game worldwide is played on a 10x10 board,

with 20 checkers per side on the first four ranks. White moves first. There

are two important differences from Anglo-American checkers: plain checkers can

capture diagonally backward as well as forward, and kings are flying kings:

they can make non-capturing moves any number of empty squares along a

diagonal (like a bishop in chess), and can capture by jumping an

opposing piece any distance away and land any distance beyond, as long

as they pass over only empty squares (except for the checker being

captured). Multiple captures, either by a checker or king,

are also possible; when a choice of captures is available, the largest

number of opposing pieces must be captured. A checker

which reaches the last rank, but which still has an available

(backwards) capture, must make that capture and is not

kinged; only a checker which finishes its move on the

last rank is kinged. In some books it is referred to

as Polish Checkers (probably a misnomer; it did not originate in Poland)

or Continental Draughts.

A consequence of flying kings is that endgames with two kings versus

one are drawn; it takes at least three and usually four kings to force

the capture of a single opposing king (but see alternate

demotion rules). Despite this, the

International game is much less drawish than the Anglo-American

variant, and richer in tactics.

International Draughts is also played on an 8x8

board with the same rules (White moves first, checkers capture backwards, flying kings,

and maximum captures) and 12

checkers per side. This is now officially called

Brazilian Draughts (older sources called it German Checkers, or

Damenspiel, but German rules do not allow plain checkers to

capture backwards). A backwards capture can

occur as early as Black's second move: e.g. 10-14 22-17; 11-15 17x19

(capturing 14 forward and 15 backwards). Spanish Draughts is similar to Brazilian except that plain checkers cannot capture backwards

(Spanish Draughts also rotates the board so that the double corner is

to the left; Portuguese Draughts is the same as Spanish but with the

double corner on the right as usual).

Spanish Draughts, as described in older books, is

sometimes played with each player having one or two kings each on their

king rows at the start of the game.

American Pool checkers

The

official rules of American Pool do not require the maximum number

of captures to be made, but a capturing piece must still continue to

capture as long as captures are available. Captured pieces

are all removed at the end of the turn. Otherwise it is the

same as Brazilian Draughts. A few older books refer to it as

Minor Polish Checkers.

Russian Draughts (шашки)

This variant, dating back to 1884, is played on an 8x8 board with most

of the International rules, with the following exceptions: a checker

which reaches the last rank by capture becomes a king immediately and can continue to capture as a king on the same

move.

Any capture, not necessarily one allowing the most pieces to be

captured, may be played when multiple captures are available, but a

piece which has made a capture (including a checker just kinged) must

continue to capture on the same turn if a capture is

available. Russian draughts players have adapted easily to

American Pool, which only lacks the continuation capture of a checker

just kinged.

Russian draughts

is also sometimes played

on a wider 10x8 board

(10 files and 8 ranks) with 15 checkers per side. This is

sometimes called Spantsireti after its inventor, Nikolai Spansireti,

but is usually called 80-Squares Checkers (80-клеточные

шашки). There are a number of other variants of Russian draughts, including:

(1) Northern Checkers (Северные шашки), where a captured king is not removed, but demoted to a plain checker.

(2) Simple Checkers (Простые шашки), in which checkers do not promote

(checkers cannot move once they reach the last rank, except to capture

backwards).

(3) Double-Move Checkers (Двухходовые шашки), where players move twice per turn. (It is not played in balanced doublemove fashion: White makes two moves even on their first turn).

(4) Giveaway Checkers (поддавки шашки),

played with Russian rules. It has been widely studied in

Russia, and tournaments have been played since 2011.

Canadian Draughts (Grand Jeu de Dames)

International Draughts on a 12x12 board, with 30 pieces per player on

their first five ranks. Malaysian Checkers (also played in

Singapore) is similar to Canadian, but plain checkers cannot capture

backwards, and the huffing rule is still in effect. In Cape Town, South Africa, a variant called Dumm is played on a 14x14 board.

Czech Checkers (Česca Dáma)

International Draughts on an 8x8 board, but plain checkers are not

allowed to capture backwards (so opening theory should be similar to Anglo-American). Played in Slovakia with only 8

plain checkers per side.

In most countries with their own regional variants, one or more of the

major variants (International 10x10, Brazilian 8x8, or Anglo-American)

is also played, particularly in official competitions.

Frisian Draughts

One

of the most interesting regional games, played in The Netherlands for

over 400 years, is played on the

10x10 board as in International draughts. Although it is played

only on the dark squares, captures can also be made orthogonally,

leaping

over two light squares as well as an opposing piece. Captures by

both men and kings are allowed in all eight

directions. Men move diagonally one square forward when not

capturing. Kings move as bishops in chess, and capture by long

leap. A multiple capture must capture pieces of the

largest available total value (counting kings as just below

1-1/2). If values are equal, a capture must be made by a

king rather than a man. An

individual king can only make three consecutive non-capturing moves

(unless a player has only kings). The World Championship Frisian Draughts

site has an excellent basic strategy manual (including openings and

endgames) in five languages, rules in six languages, and additional

books in Dutch. Recently a miniature version, Frysk, with only

five pieces per side, has been introduced. Both Frisian and Frysk

are featured on the LiDraughts server.

Full board Orthogonal variants

[Movement is orthogonal; every square is available]

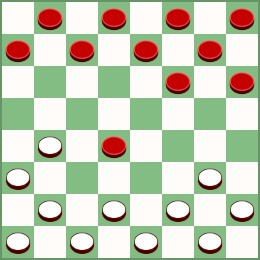

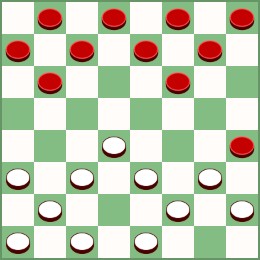

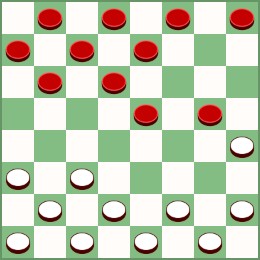

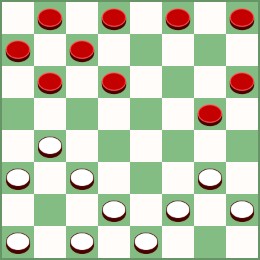

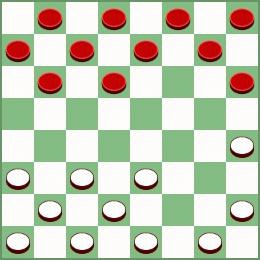

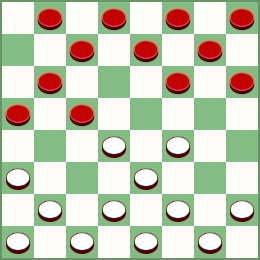

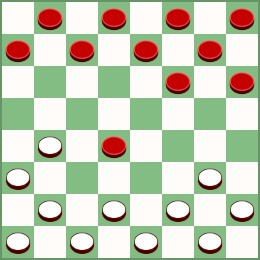

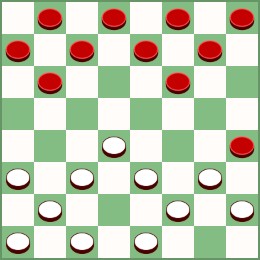

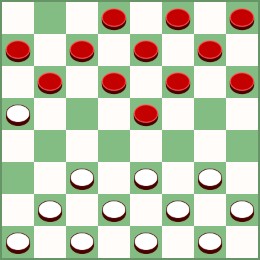

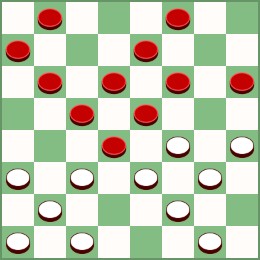

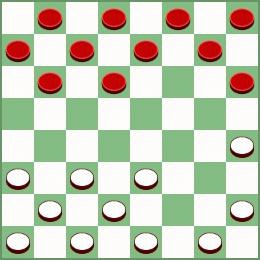

Turkish Draughts (Dama)

The principal variant in which all 64 squares are

used. It is played in Turkey, Greece, Egypt, and the Middle

East. The first world championship was not held until 2014,

though the game is far older, and likely evolved independently of the

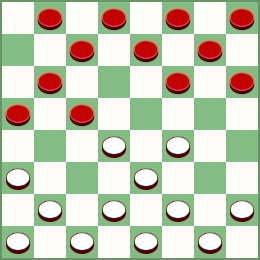

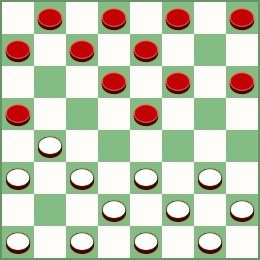

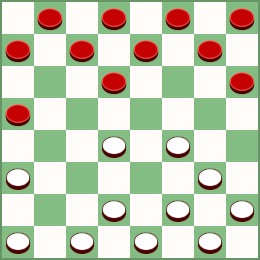

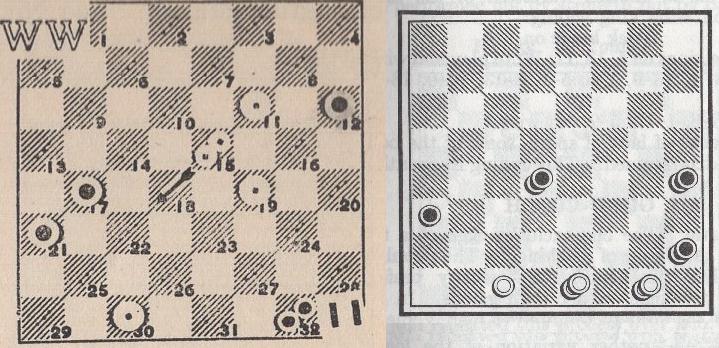

diagonal variants. Each player has 16 pawns, placed on the

second and

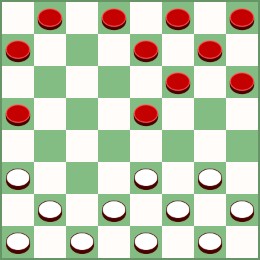

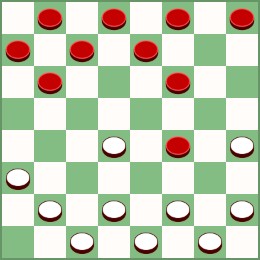

third ranks (diagram above, although traditional boards are

uncheckered). Pawns

move one square straight

forward or sideways, and capture by jumping in the same

manner. A pawn which finishes its move on the last

rank

is kinged; a pawn which jumps to the last rank can continue with

sideways capture if available (and is still kinged). Kings

(Dama) can move and capture any distance in any

orthogonal direction. Pieces in multiple captures are

removed as each is jumped; this may make new captures available;

reversal of direction (180 degree turn) is not permitted.

The maximum number of captures available must

be made. Like Anglo-American checkers, two kings can win

against one in the endgame, and the draw rate is lower than the other

major variants. { The description in The New Complete

Hoyle and Goren's Hoyle

is erroneous: they allow diagonal forward movement, probably confusing it with

Armenian draughts, another regional variant.}

Turkish draughts is the basis for an excellent modern variant, Give and Take,

invented by Christopher Elis, described later under Modern

Variants. Two other modern variants, Croda (see Abstract Games 9)

and Dameo (also in Modern Variants below), are more closely related to

Armenian draughts. Another regional variant of

Turkish draughts is Keny,

played in the Caucasus (Russian кавказские шашки, or Caucasian

Draughts), in which pawns can capture in all four directions, as well

as make non-capturing leaps over friendly pieces (as in Halma).

Variants to reduce

draws

Because the Anglo-American game has a very high rate of draws among

expert players, a number of variants have been devised to vary the

opening play:

Eleven-Man Ballot (Newell W.

Banks, 1907) -- each player removes one

checker

from the start, from squares chosen at random from a special deck of 8

cards. A second card drawn by each

player gives their first move to be played. 2500 distinct

opening

positions are possible in all; Ed Gilbert's Kingsrow program identified

247 as losses, leaving 2253 playable

openings. The Checker Maven has a good account of Gilbert's work. Goren's Hoyle describes a more limited version, in which the two pieces removed are

from corresponding positions (e.g. 6 and 27). Other systems have also been

used, including special 12-sided and 4-sided dice devised by Don

Brattin, based on an idea by Bill Scott. A detailed

description of various systems for 11-man

ballots is on the website of the North Carolina Checker Association. W.R. Fraser's The Inferno of Checkers gives a few sample games, and indicates how the openings can occasionally be steered into normal three-move openings.

Contract Checkers (L.S.

Stricker, 1934) [source: Goren's Hoyle; Games Digest June 1938]

Play starts with 12 checkers a side in the usual array. There are

one, two, three, or four extra checkers per side in reserve. One checker

each is added simultaneously to each side when designated pairs of back

row squares are vacated (e.g., in the 13-checker variant, each player

adds a reserve checker as soon as both 4 and 29 are vacant). Talis' description in Games Digest

suggests only one extra checker per side, placed simultaneously as

soon as any pair of corresponding back row squares become vacant.

Two- and Three-Move

Ballot -- See Appendix 1.

Balloting for opening moves

is now used in international 8x8 (Brazilian draughts) tournaments, with 780 possible combinations of

up to three moves per side (e.g. combination 11 XVII is a longer line in

the equivalent of the American opening Gemini 2: 10-15 23-19; 11-16

19x10; 6x15 22-17). Some of the ballots use a system called flying checkers,

in which one or two pieces are moved from their opening position to a

square to which they could not move normally (e.g ballot 23 IV moves a3

to d4 and h8 to h4).

King Demotion

Rules

In Draughts variants with flying kings, it normally takes four kings

to defeat a lone king. (In 8x8 variants, three kings can

defeat one king if the stronger side has a king on the long diagonal

between the single corners, using a technique usually called a Petrov

Triangle.) An alternate rule to fix this is to require a

king, when capturing an opposing king, to stop in the square immediately beyond the

captured king,

rather than being allowed to fly further after capturing (this is a

standard rule in some regional variants like Thai

Checkers). Christian

Freeling calls the game with this rule Killer Draughts. It

has the effect that two kings can win against a single king, instead of

requiring three or four. Juri Anikejev suggested a

more limited rule called Modern Draughts (Killer Light) by applying the

rule only after capturing a king at the end of a multiple capture

sequence. In Central-South-German Checkers (Süddeutsches

Damespiel), a king must stop in the square immediately beyond the last captured piece. See Peter Michaelsen's post for some history of these rules.

Herman Hoogland, a World Champion player from the Netherlands,

borrowed a rule from Frisian Draughts to allow two kings to defeat one:

a king can

capture an opposing king orthogonally. In 2020 on the BoardGameGeek

forum, Michał Zapała proposed a new variant, Constitutional Draughts,

in which a king making a non-capturing move could not pass through an

attacked square to reach a non-attacked square (capturing moves are

unaffected); this also allows two kings to defeat one (a short introduction is here).

Breakthrough

The first

player to make a king wins (also called Kingscourt, not to be confused

with the commercial variant King's Court described below).

This is sometimes used as a

simpler variant to teach beginners the basics of strategy.

It is supported as a variant on Lidraughts,

but can obviously be played with almost any variant. Martin

Fierz solved the version for 8x8 American checkers in 2006 (White has a forced win in about 31 moves).

Alternate Opening Positions

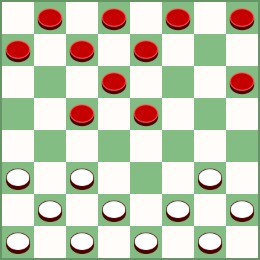

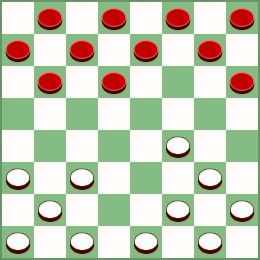

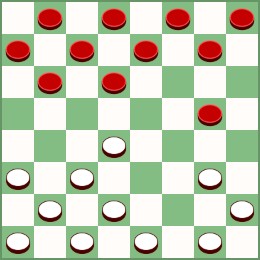

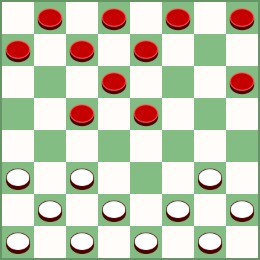

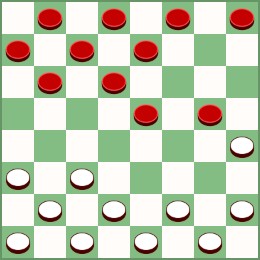

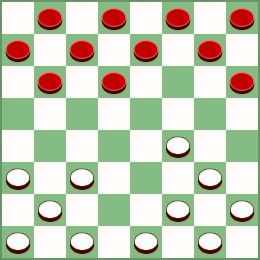

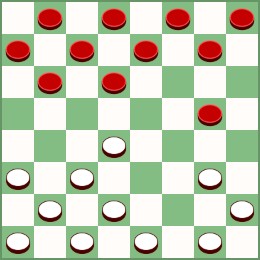

Diagonal Checkers

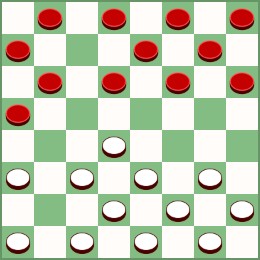

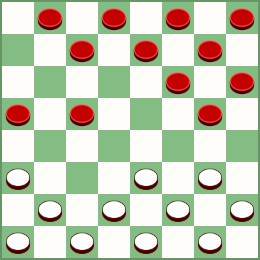

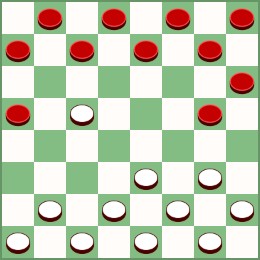

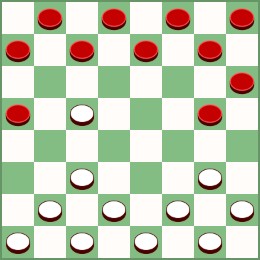

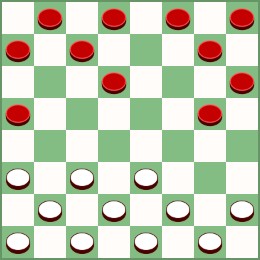

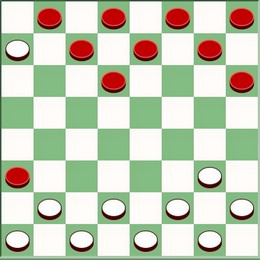

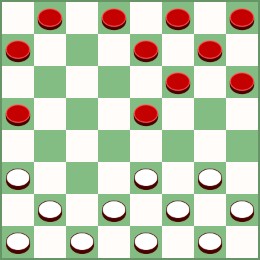

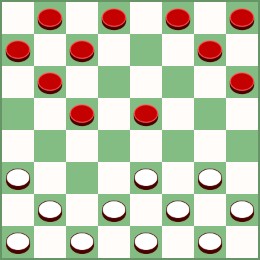

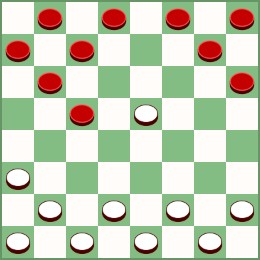

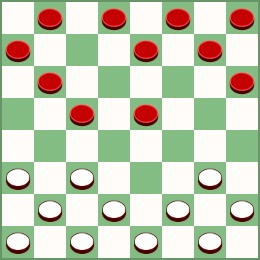

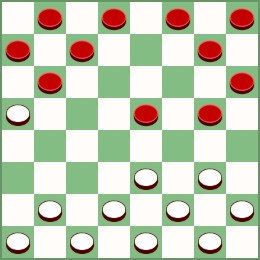

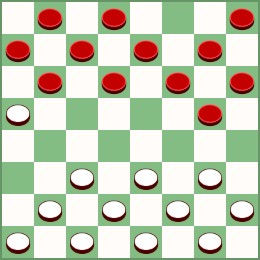

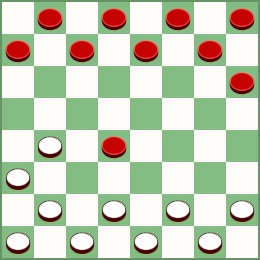

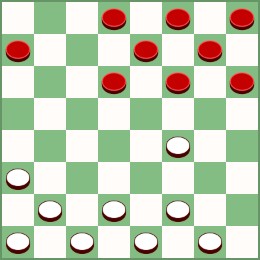

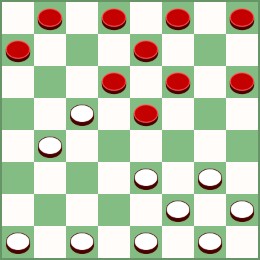

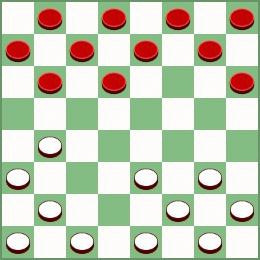

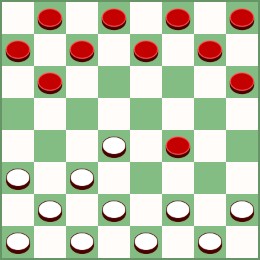

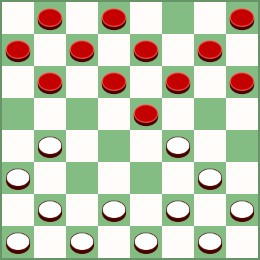

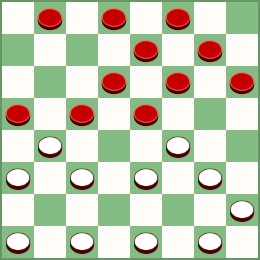

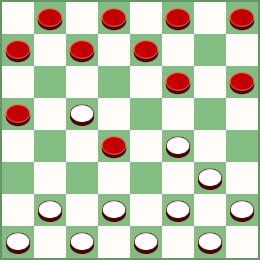

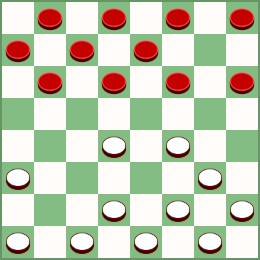

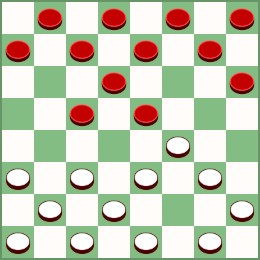

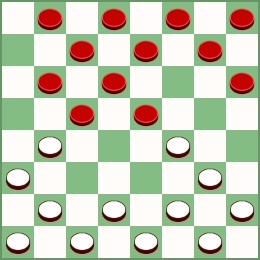

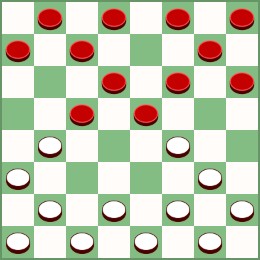

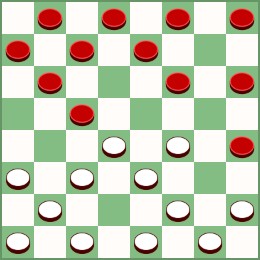

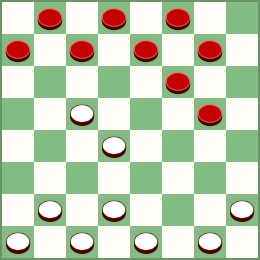

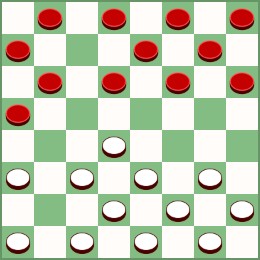

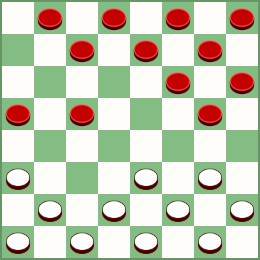

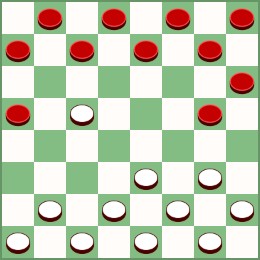

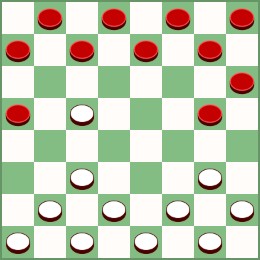

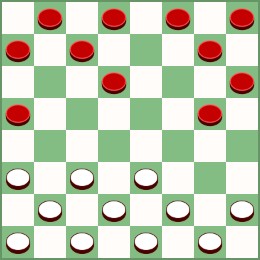

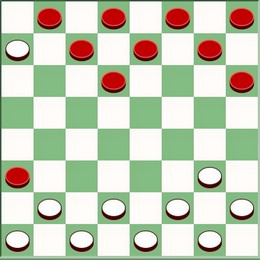

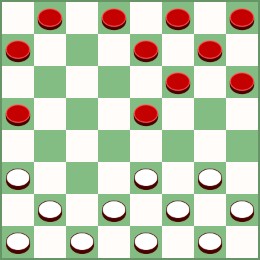

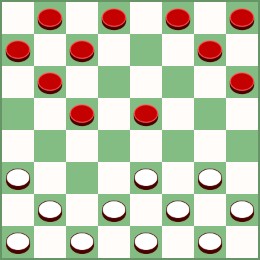

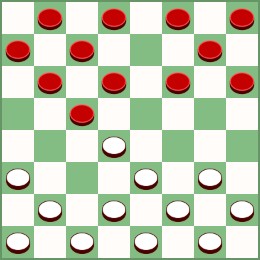

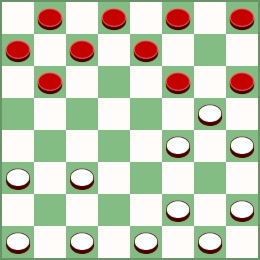

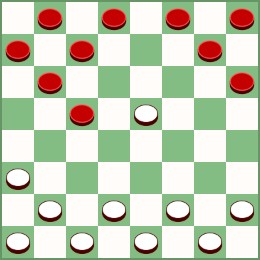

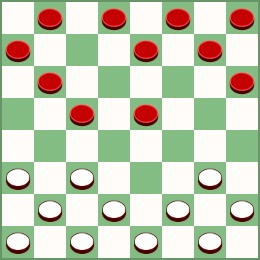

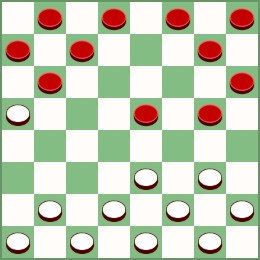

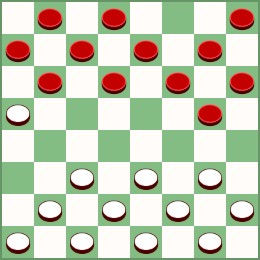

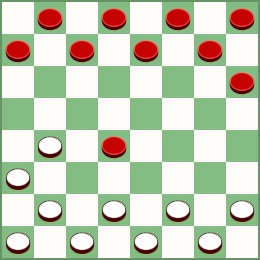

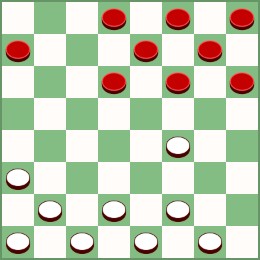

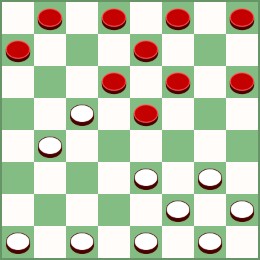

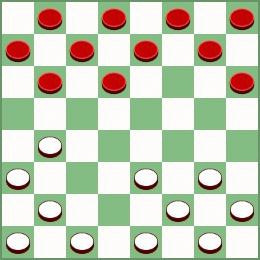

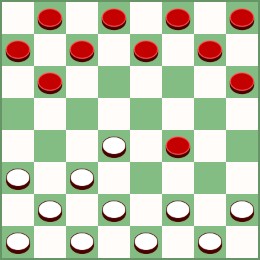

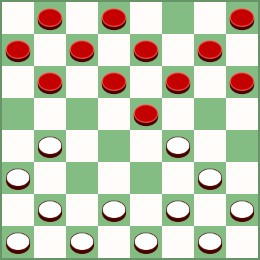

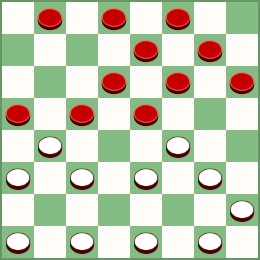

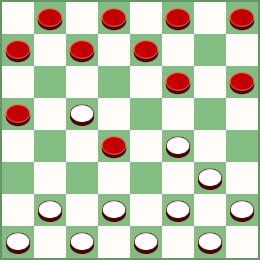

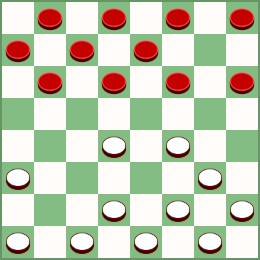

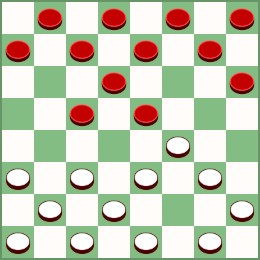

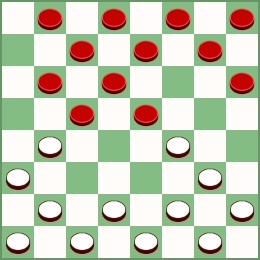

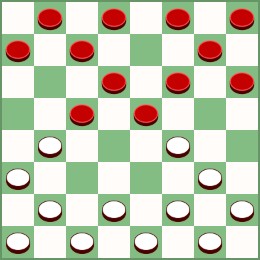

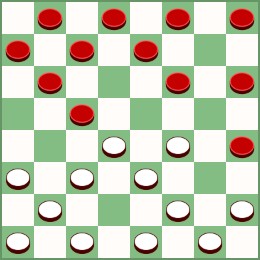

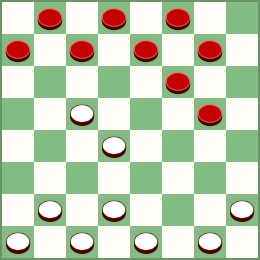

Diagonal checkers (in the 12-piece version above left) is a

common variant for American checkers, and also in both Russian and

German draughts. Pawns promote to Kings in either of the two

opposite double corner squares (German: a7b8 or g1h2) or any of the four edge squares

farthest away (Russian: a5a7b8d8 or e1g1h2h4). There is also a 9-piece variant (above right).

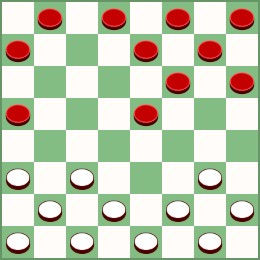

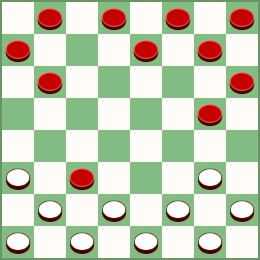

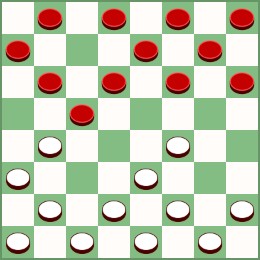

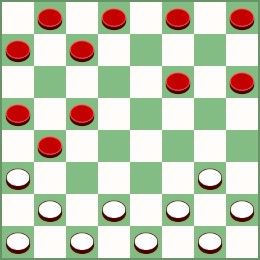

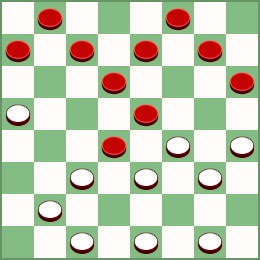

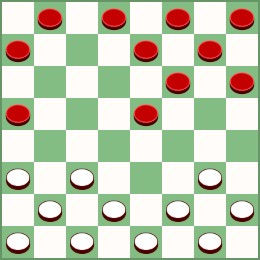

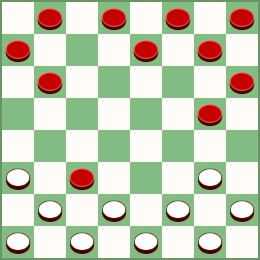

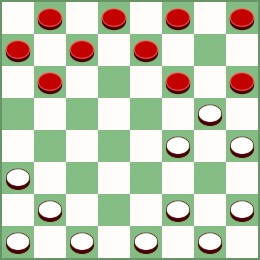

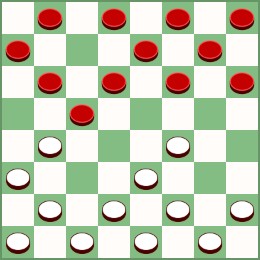

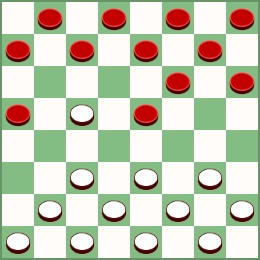

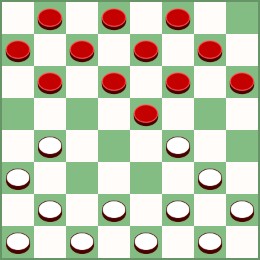

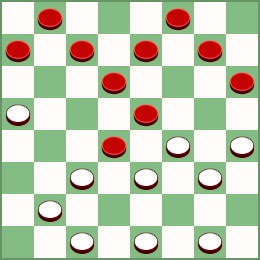

Parallel Checkers

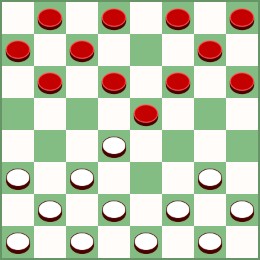

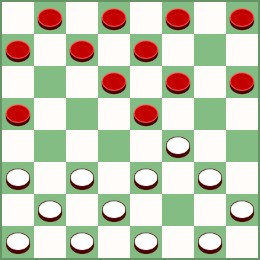

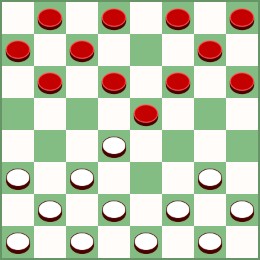

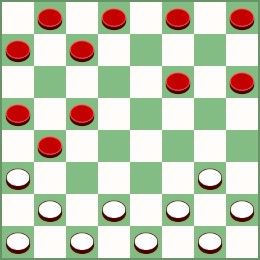

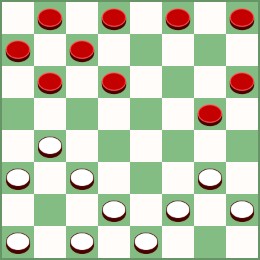

Parallel Checkers (Les Dames Paralleles, ou A Sens Unique) (Joseph Boyer)

From the book by Boyer and Parton; both players move and promote in the

same direction (moving up the board); Boyer does not specify which

player moves first. It can be played with any of the usual

variants; the game server BrainKing

implements it as One-Way Checkers, on an 8x8 board using Czech Checkers

rules (no backwards captures by plain checkers). Boyer also

suggests 12x12 Canadian checkers; the starting position is more

balanced when both players have the same number of checkers on their

uppermost row (8x8 or 12x12).

Super-checkers (Charles Fort) c. 1930

A giant variant played with many checkers per side on a large

checkered cloth. Players were allowed to make large numbers

of moves at a time at the opponent's discretion, followed by an equal

number by the opponent. The author wrote

to a friend: "Super-checkers is going to be a great success. I

have met four more people who consider it preposterous."

Modern Variants

Checkers to the MAX (Stanley

Druben), 1992

The board starts empty. Players alternate either placing a

new checker on a vacant square on their first three rows, or moving a

checker already placed.

Coronet (Chris Huntoon), 2012

An 8x8 variant with both orthogonal and diagonal movement, with 21

pieces per side arranged in a triangle in opposite corners.

Promotion is only in the single square in the opposite

corner. Implemented in Zillions. This article on BoardgameGeek gives a number of Huntoon's inventions.

Dameo

(Christian Freeling)

An 8x8 draughts variant using the whole board, with king movement in

all eight directions; developed from Croda. Checkers can only move straight or

diagonally forward, but can perform a linear jump, passing over one or

more adjacent friendly checkers in any of the three directions (this is

equivalent to shifting a whole row of adjacent pieces one square in the

same direction, a limited version of the phalanx move in Robert Abbott's game Crossing/Epaminondas). Kings cannot perform a linear jump, nor be

jumped over. Captures are orthogonal only, but in any

direction (checkers by short leap, kings by long leap). The

tactics of the game are rich, and draws are infrequent. Two kings

can always win against one king, regardless of the position and which

player is to move. The Bibliography lists an excellent

introductory book by Aleh Tapalnitski, Meet

Dameo!, which is available for free download.

Give and Take

(Christopher Elis)

This is a variant of Turkish draughts with the same general rules and

opening position, but there are two new rules

which make the game rich in tactics. The first new rules is

that captures are only

compulsory in one instance: when a piece is moved so that it can be

captured, the opponent must immediately capture it, and continue to

capture if possible (this is the Give and Take of the

title). A king which captures must land on a square

permitting another capture if possible. The second rule is

that a pawn which is a

player's only piece instantly becomes a king. John

McCallion published an account in NOST-Algia

339, and a feature article in Games

Magazine (May 1999, pp. 56-57). It was also discussed in Eteroscacco 62.

Giveaway Checkers (The Losing

Game, Anticheckers, etc.)

This is the misčre variant of checkers: the object is to lose all of

your pieces (or have the remaining ones blocked). This can be played with any variant of the

normal game with compulsory captures. Recreational Mathematics Magazine volume

1, number 2 (April 1961) gave a 56-move solution

to a straight checkers problem (Loser's Checkers) where White (with a

full set of checkers) must win by forcing a single Black king at 7 to

capture all 12 men. It was a popular game in NOST, and

has been widely played in German (Schlagdame) and Russian (поддавки шашки) draughts.

The Good-for-Nothings (Les Vauriens)

V.R. Parton devised a game (first published in the book by Boyer and

Parton) combining regular and giveaway checkers. It is played

like International 10x10 draughts, but the five checkers on each

player's back row are replaced by Good-for-Nothings,

which move and capture like normal checkers, but lose the game if

forced to promote. The goal is to lose all five of your

good-for-nothings; you can also win by capturing all of your opponent's

regular checkers, or by forcing an opposing good-for-nothing to reach

your back row and promote. Schmittberger describes this in New Rules for Classic Games, and suggests that it can be played on an 8x8 board as well. ItsYourTurn implements it with American rules as Mule Checkers.

Heaven and Hell Toroidal

Checkers

Frank Cunliffe sent me rules for this very

interesting game from a

one-page posting on a Princeton computer network written by Tobias D. Robison, who learned the game in 1958

from Joe Tamargo. [Can

anyone shed any more light on the origins of this game?]

The game starts in the normal 8x8 position, and checkers and kings move

and capture as normal. However, the board is toroidal

(doughnut-shaped): the two end ranks are adjacent, as well as the

leftmost and rightmost ranks. The dark squares are referred

to as Heaven, the light squares (initially all empty) as

Hell. Checkers do not promote by reaching the last rank;

kings can be created only by capture. When a piece is jumped, it

is shifted horizontally (along its rank) to the jumping player's left,

to the first available square of the opposite color which is either

vacant or occupied by a single checker of the same color (in which case

it creates a king). A king which is jumped can only be

shifted to an empty square. If no squares are

available, the jumped piece goes into Limbo (off the board and

permanently out of play). Once a player has pieces in both

Heaven and Hell, they may play in either, but a capturing move must be

made if available anywhere (pieces jumped in Hell shift back into

Heaven). The object is to get all of the opponent's pieces

out of Heaven. (As Robison puts it, you are simultaneously

playing regular checkers in Heaven and losing checkers in

Hell). I passed the information to John McCallion,

who wrote a feature article for Games

World of Puzzles May 2012 (pp. 66-67), including a sample game.

Hexdame (Christian

Freeling)

International Draughts on an order-5 hexagonal board, with 16 checkers

per side. Rules are given on pp. 183-184 of New Rules for Classic Games.

Kiwi Checkers (John Bosley)

This is a variant which uses the shogi mechanism of dropping

(re-entering captured pieces). When pieces are captured, they are

added to the capturing player's reserve, and can be dropped 1, 2, or 3

at a time onto vacant squares or onto friendly pieces; stacks of up to

three pieces are allowed, named after birds from the inventor's native

New Zealand. Single (kiwi) and double (tui) pieces move as

regular checkers; triple (moa) pieces as kings. Checkers

which reach the back rank are not kinged; they are immobile until

pieces are played from the reserve to form a Moa (stack of

three). Captures are mandatory and the maximum number

of captures is required. A drop constitutes a move and is

only allowed when no captures are available. Kiwi Checkers was

first published in 1990 in NOST-Algia

319, and briefly described in WGR10

in 1994 (p.29).

March Hare Checkers (Chris Huntoon), 2012

Application

of V.R. Parton's March Hare Chess to 10x10 International

Checkers. After Black's first move, each move consists of

moving a friendly piece followed by an opposing piece (captures

mandatory as usual). A player reduced to one or two pieces

loses. Implemented in Zillions.

Sleeping Beauty Draughts (Ralf Gering)

Published in Abstract Games 14 (Summer 2003, pp.25-26), this is a modern variant designed to make draws impossible. Rules are as Anglo-American checkers, but men promote to ladies,

which can capture either as regular kings (shortleaping), or by

replacement (as the chess Fers, one square diagonally). A

player may only have one lady at a time; additional promotions are to sleeping beauties,

which remain stationary (unable to capture or be captured) until a

player loses their only lady, at which point a sleeping beauty can be

awakened. Full rules and five sample problems are

available in the online issue.

Combinations

of Chess and Checkers

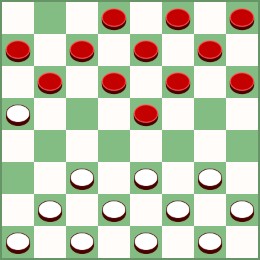

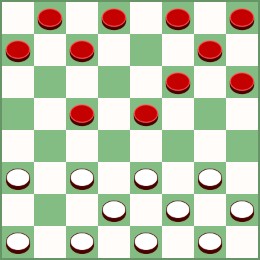

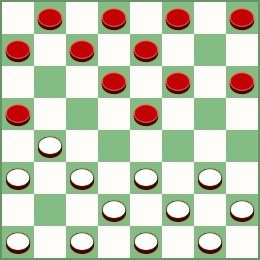

Initial position in Cheskers

Cheskers (Solomon W. Golomb),

1947

This is a combination of chess and checkers, invented in 1947 by

Solomon W. Golomb, of pentominoes fame. The board and

opening

position are exactly as in checkers, except that the four first rank

checkers are replaced by: a Bishop at a1/h8 (which moves exactly as in

chess, capturing by replacement rather than by leaping), two Kings at

c1/e1/d8/f8 (which move exactly like kings in checkers), and a Cook at

g1/b8 (which moves like the Camel in chess variants, to the opposite

corner of a 2x4 rectangle, capturing by replacement). [Knights

are used for the Cooks in both diagrams and play.] The

second and third-rank pieces are Pawns, which move and capture exactly

as checkers; multiple captures are as usual.

If captures by Pawns and/or Kings are available, a capturing move is

mandatory, but may be by Bishop or Cook if available. Capturing

by Bishop or Cook is always optional. Pawns which

reach the last rank promote to Bishop,

Cook, or King. The object is to capture all of the opponent's

kings. A stalemated player loses. This was a

popular variant game in the Knights

of the Square Table.

Chess-Draughts (Henry Richter, 1883)

Not really a checkers variant; although play is on the black squares

only, capture is by replacement rather than leaping. Each

side has 6 Pawns (moving and capturing one square diagonally forward,

and promoting to Knight on the last rank), one Lady (one square

diagonally in any direction), and one Knight (like a bishop in

chess). The object is to capture the opposing Lady.

Commercial Variants

Blue and Gray (Henry Busch and Arthur Jaeger), 1903

Checkers variant played on the intersections of an 8x8 board (i.e. 9x9 intersections) with 17 guards and a captain

on each side. The board has a specially marked path from the

starting square of both captains to the center of the

board. The object is to reach the center with the

captain. Described by Sid Sackson in A Gamut of Games.

Camelot (George S.

Parker), 1930

One

of the most renowned commercial variants of checkers, invented by the

founder of Parker Brothers. It originally appeared as

Chivalry in 1887, then as Camelot in 1930. It is played on

a vaguely octagonal board of 160 squares (12 wide and 16 deep, with the

first three ranks at each end reduced to 2, 8, and 10 squares), with

ten men and four knights per side. There are several

different kinds of moves, some of them similar to Halma. It

was briefly republished in 1985 as Inside Moves, without the medieval

imagery. Other variants have been published by Parker

Brothers, and unofficial variants have also appeared. Wikipedia

has a good description, including a sample game from the 2009 world championship. There is also a World Camelot Federation.

King's Court (Christopher

Wroth), 1986

Checkers variant on an 8x8 diamond-shaped board, which starts full

except for the 4x4

central area. Pieces move and jump as kings, and can also jump

friendly pieces without capturing. Each player moves one

piece into the central area: the first player to eliminate all of the

opponent's central pieces wins.

Quick Checkers (Amerigames International), 1998

A commercial 6x6 version (6 pieces per side) designed to teach

children how to play. The other side of the board has a standard 8x8

board.

Multiplayer Variants

Three- and four-handed versions of checkers (with each player moving in a different direction) are too numerous to mention

them all (similar chess variants have existed for a century or more). A number of examples can be found in Boyer and

Parton's book, including triangular and hexagonal

boards. A three-handed game on a triangular board, called Draughts For Three, was patented in 1888 by

John Hyde (see Provenzo, Play It Again, in the Abstract Bibliography); a different scheme, Trangle Checkers, was published in 1897 by Warren Morris Babbitt (see the Bibliography below). Four-handed commercial examples include George V. de Lery's Fourplay Checkers (Deroma, 1939), on a 6x6 board with four 2x6 wings added and only six checkers per side (mentioned in Wiswell and Hopper's Checker Kings in Action), Robert King's Intense Checkers

(1991), on an 8x8 board with four 3x8 wings added, and Elmer C. Pearson's Fourhanded Checkers (1974), on an 11x11 board with corner squares removed, and 9 checkers per side. Three-handed versions include Megacheckers

(MegaGames), for three players on an oddly-shaped board with 12

checkers per side, En Garde (Mynd Games, Northern Games, 1986), on a

nine-sided board, and Yorel Game Company's Treckers (1981), on a hexagonal

board for 2 or 3 players, with five levels of play. Board Game Geek has details on many other commercial checkers variants.

Distant relatives of checkers

To keep this guide to a reasonable size, I have omitted several families of games:

(1) Games where captured pieces

are absorbed into a stack, such as the traditional Russian game Bashni

(Columns), and its later offshoots like Emmanuel Lasker's Laska, and

Christian Freeling's hexagonal variant Emergo. Winning

Moves' King Me includes a

variant called Stack'Em Checkers in the same family. David

Pritchard, in both The Family Book of Games and Five Minute Games,

mentions Alvin Paster's game of Pasta, which combines

Laska and Checkers. There are also games where jumped

pieces are flipped as in Reversi. The New Complete Hoyle

describes a variant called Stack-Up Checkers (credited to Mark Eudey

and Stillman Drake).

(2) Games in which

there is no capturing (Halma and its relatives like Chinese Checkers,

and checkerboard variants such as Pyramid Checkers and Salta (a brief craze in the early 20th century)), where the object

is to move all of your checkers into the opponent's starting area.

(3) Games of the Fox and Geese and Tafl families, which have unbalanced

forces and different goals, and in which neither side, or sometimes

only one side, can capture.

Konane (Hawaiian Checkers)

A

Hawaiian game with 32 pieces per player, which fill the entire board

in

alternation (that is, black pieces start on what would be the black

squares and vice versa, though the board is uncheckered and

traditionally consists of pits dug into a stone board, with white

pieces of coral and black pieces of lava). Two adjacent

pieces, usually near

the center, are removed. Not a checkers variant, since

pieces can't make non-capturing moves: captures are mandatory and

orthogonal

only;

multiple captures are not mandatory and are allowed in only one

direction per turn. The last person

able to make a capture wins.

Notation and Diagrams

In

traditional Anglo-American notation, the playable squares are numbered

from 1-32, starting at the upper left corner from the first

player's viewpoint. Black moves first from the top half of

the board. Moves are designated by the starting

and

finishing square separated by dashes (11-15) or spaces in older books

(11 15); sometimes captures are

noted by x or : (11-15 22-18 15x22). Some older books (e.g.

Anderson, Baker, and as late as Kear's Encyclopaedia) which present moves in vertical columns may have

dashes (sometimes long) in Black's moves and spaces (or double dots) in White's, to make the pairs of

moves easier to see. International Draughts

also uses numerical notation with the numbers 1-50 (x for

captures), with White moving first from the bottom half of the board. Standard algebraic

notation is used in Russian and Turkish

Draughts (necessary in Turkish, since all 64 squares are used). Portable

Draughts Notation

is a text-based notation which is both human and machine readable, and

has options for many different variants. It supports

annotations

as well as information on when and where and by whom a game was

played, and uses traditional numeric notation with x for

captures. It was devised by Adrian Millett (based on the

existing Portable Games Notation) for his programs Sage and Dynamo, and

has been adopted by many other draughts programs.

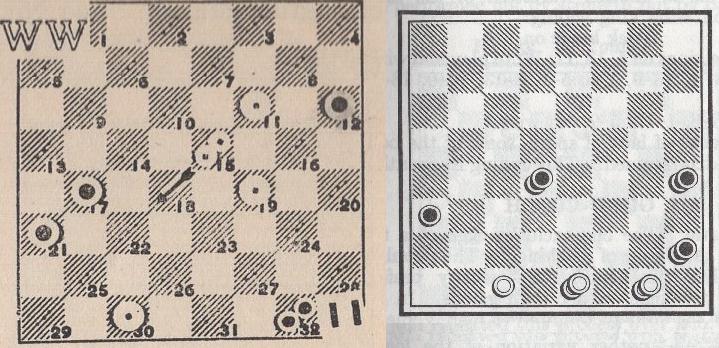

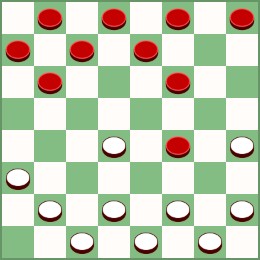

Numbered Board for 8x8 checkers

Diagrams

Although play is on

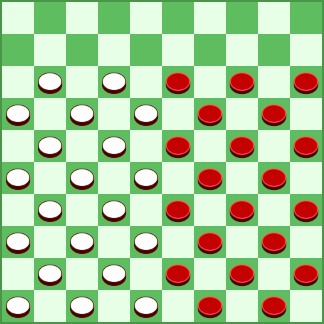

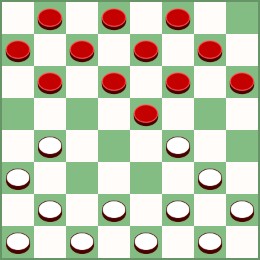

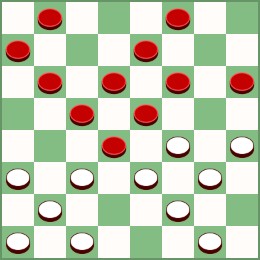

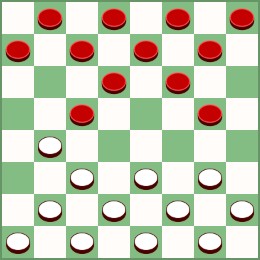

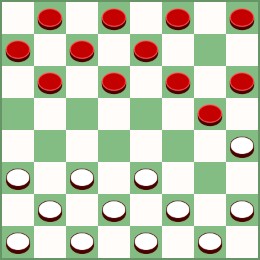

the darker squares, printed diagrams in monochrome are usually made

with

reversed colors, so the pieces are shown on white squares, with the

unused squares in gray. Monochrome diagrams printed with the

pieces on

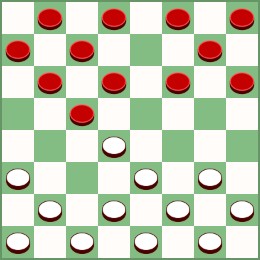

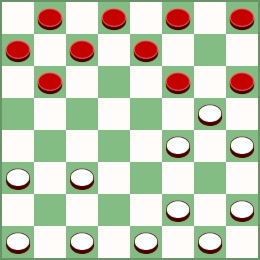

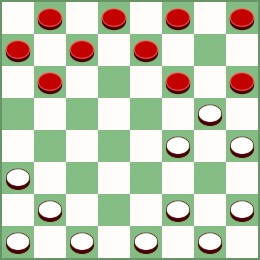

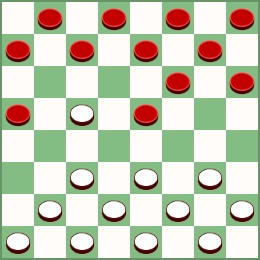

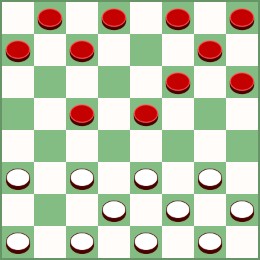

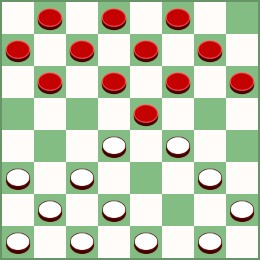

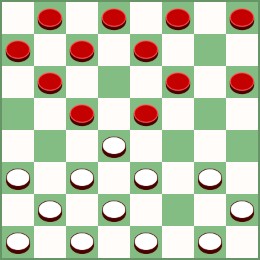

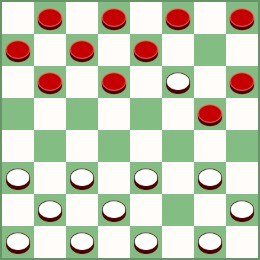

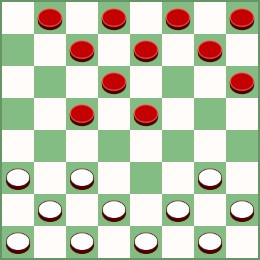

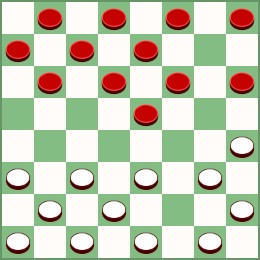

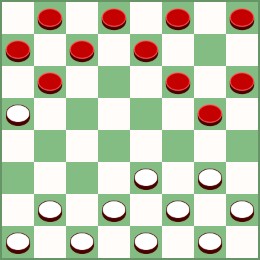

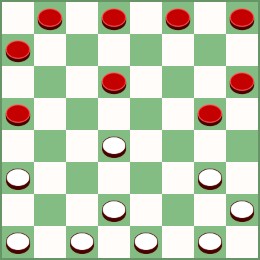

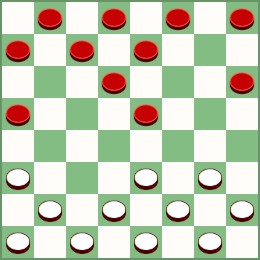

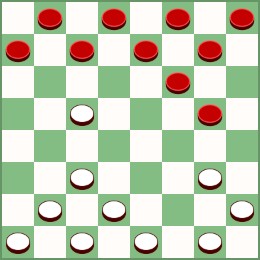

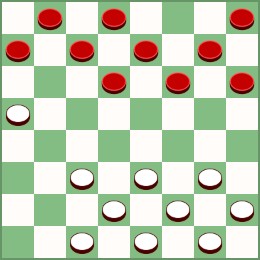

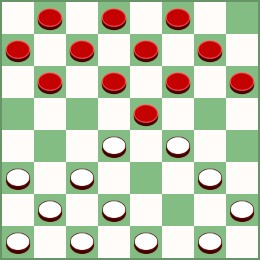

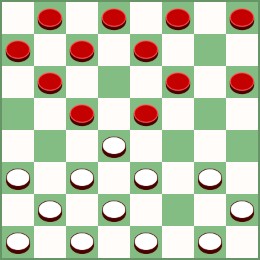

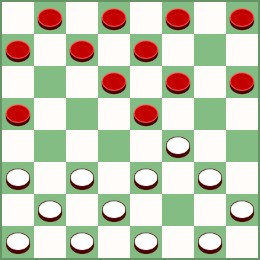

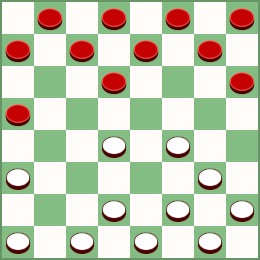

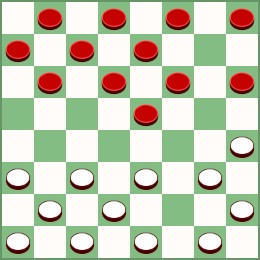

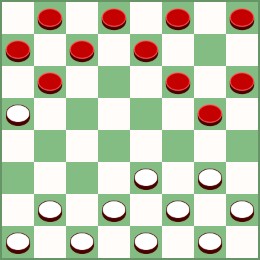

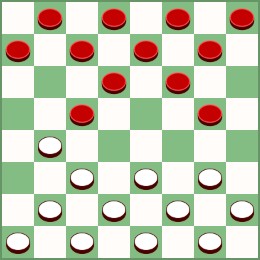

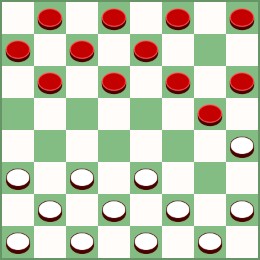

dark squares are often nightmarishly unreadable: below are diagrams

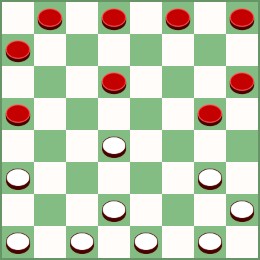

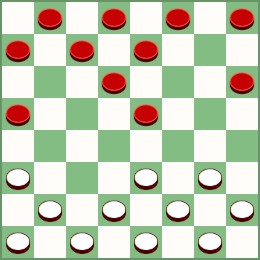

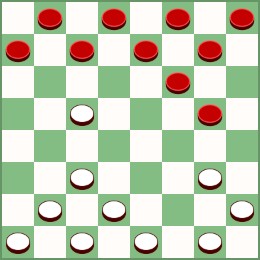

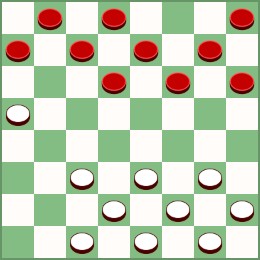

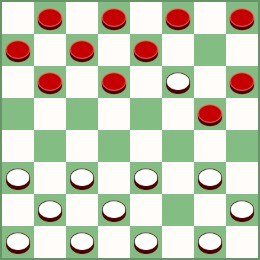

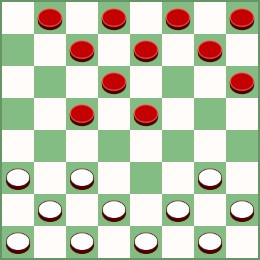

from two different books by the same author, Andrew J. Banks. The left

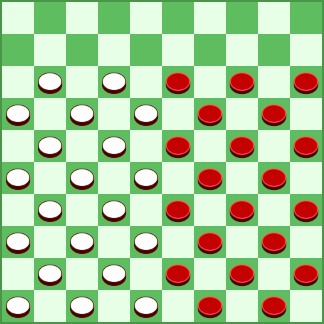

diagram is from Pictorial Guide to Checkers; the right is from Checker Board Strategy.

Despite being here reduced 50% relative to the first diagram, the

second is much sharper and clearer. In electronic

publishing (like this booklet), quality diagrams can be published in full color with pieces

on the green squares.

Software

Aurora Borealis Draughts by Alexander Svinn

A powerful and flexible program with options for 14 variants (all of the major variants, even Turkish and Frisian).

CheckerBoard by

Martin Fierz

A very versatile program with its own strong playing engine (called

Cake), opening book,

endgame databases, fine graphics, and facilities for reading and saving games in

PDN and positions in

FEN formats. It also acts as an interface to other programs

like Kingsrow.

Chinook by

Jonathan Schaeffer et al.

At

one time the strongest 8x8 checkers program, which won or drew several matches

against

top players. Even early versions were notable for large

endgame databases. In 2007 it proved

that go-as-you-please Anglo-American 8x8 checkers is a draw with best

play, by selectively solving enough openings to show that Black could

at least draw with 9-13 regardless of White's reply, and White had at

least one reply to each Black opening that would at least draw.

By 2009 Chinook had proven 28 of the three-move openings

were drawn, notably the White Doctor (first to be proved), Double

Cross, Octopus, Tyne,

Skull Cracker, Single Corner, and Black Widow (the last one solved,

which completed the proof for the whole game). The latest version

can be played

over the web; the website has more details about Chinook, and its

endgame databases can be downloaded. Schaeffer's book One

Jump Ahead has even more detail. Today, however, Kingsrow

and Cake are regarded as the strongest programs.

Colossus Draughts by Martin Bryant

A very strong program which won a human tournament in England in 1990,

and later that year defeated an early version of Chinook to win the 2nd

Computer Olympiad. Colossus was the first program with a

large opening book (including original research, correcting published

play). Bryant later joined the development team for

Chinook.

Dalmax Checkers

Android application with customizable rules, with presets for 12

different variants. I have not seen this: it would not

install on my Chromebook.

Kingsrow by Ed Gilbert

Powerful modern program able to play Anglo-American, International, and

Italian checkers. It includes large databases of both

openings and endgames. One of the most interesting pages

on the site is an analysis of every possible four- and five-move

sequence: Kingsrow assesses 542 out of 794 four-move sequences and 1364

out of 2700 five-move sequences as drawable. This includes

odd sequences like the Charleston line 9-14 21-17 14x21 22-18 5-9?,

where Black's poor third move is the only one which allows White to

draw what is usually a lost opening (White must then play 18-15* to set

up the two-for one capture 11x18 23x5). Kingsrow's opening

book is self-generated, and contains many strong lines which have not

appeared in published play. Another valuable page is a description of conclusive results on particular lines in some well-known openings.

Nemesis by Murray Cash

Strongest program in the world in 2002; included an 8-piece endgame

database. Enhancement of Cash's earlier program

Nexus. Many analysts in the early 2000's relied on it to

check the strength of various lines, as Kingsrow is used today.

Online Draughts Diagram Maker

Most of the diagrams in this booklet were made with this web-based

package, which is easy to use and has a large variety of options.

It also has modules for chess and fairy chess diagrams.

Sage and Dynamo by Adrian Millett

Sage is a program to play 8x8 Anglo-American checkers; Dynamo Draughts

plays 10x10 International draughts. Millett developed

Portable Draughts Notation, and is also a noted chess programmer.

Straight Checkers Gold by Al Lyman

Checkers tutorial program formerly available at www.checkerworld.com. There is a short description on the Checker Maven.

World Championship Checkers Gold by Ed Trice and Gil Dodgen

First program with a perfect play database.

Wyllie Draughts by Roberto Waldteufel

Strong program of the early 2000's, including a 7-piece database.

It won a practice match against Alex Moiseyev in 2002 with 16 wins, 3

losses, and 49 draws. See Moiseyev's Sixth for details.

Zillions of Games

A versatile software package for Windows, able to play an enormous

range of board games, particularly chess and checker variants and other

abstracts, with a programmable system. The standard

package has 19 variants of checkers built in; the website

contains hundreds of games programmed by users.

Modern programs for playing checkers (as well as other abstract

board games like chess and reversi) generally have three main parts:

(1) An opening book, consisting of thousands of opening variations in a tree structure, with evaluations

(2) A middlegame engine, which searches the game tree of a position as deeply as possible. Ideally it wants to reach an endgame position with a favorable (known) result; if not, it must evaluate each position numerically to select the best line of play.

(3) An endgame database, containing millions of positions, evaluated as

wins, draws, or losses, with a method for navigating the database to

reach the best result possible (a win if one is available; a draw

otherwise if possible; otherwise the hardest possible win for the

opponent). There are at least 3 types, in increasing order of storage and I/O requirements:

(a) WDL (Win-Draw-Loss) -- gives only the result for each

position. This can lead to missed wins in complex endgames like

Strickland's Position, by repeating king walk moves without making any progress.

(b) DTC (Distance to Conversion) -- gives the number of moves before an

irreversible move is played. This can fix the problems caused

by WDL databases, but has its own flaws.

(c) Perfect Play -- gives the correct next move in each position.

Ed Trice and Gil Dodgen computed the first 7-piece Perfect Play

database for checkers, part of their program World Championship

Checkers Gold. This guarantees the shortest solution, but not always one human players can follow.

Bibliography

Most of this bibliography covers Anglo-American checkers, and

nearly all of the books listed are in English (there are numerous books

in Russian, Dutch, and French on other variants of

checkers). It is nearly impossible, and certainly

impractical, to try and list every book and magazine devoted to

checkers. The largest collection of checkers books is probably the John Caldwell/Irving Windt Checker Books Collection,

assembled by Don Deweber, which is now located at the Loras College

Library in Dubuque, Iowa. It has well over 7000 books,

pamphlets, and magazines. I have tried

to identify the most important and frequently cited books, particularly

those considered standards in the field, and everything I can find by

the most important and prolific authors such as Boland, Ryan, and

Wiswell. General books on games with sections on checkers

are omitted, with a few exceptions. Nowadays there are several

very poor self-published books by non-experts (either print-on-demand

or in Kindle

format), which are not listed here.

Many of the works listed here are in my own

collection. As usual, pictures of the cover indicate

books which are highly recommended. Basic

bibliographic information on

other books has been gathered from a variety of sources, including

Call's The Literature of Checkers, Google

Books, WorldCat, HathiTrust, the Library of Congress; bookdealers (Bookfinder,

Amazon, Biblio, ABEBooks, Alibris, and eBay), and from online reviews on

Checker Maven and Start Checkers. Many books are

available online: some for

download, others for online reading only.

Bulletin of the Brooklyn Public Library

The 1922 edition, available at Google Books,

includes a three-part listing of checkers books (October-December

1922). This includes quite a few books published after Call

(see below).

Call, William Timothy -- The Literature of Checkers, 1908, Call, New York, 72 pp., $1.00

Bibliography of 227 books and magazines in chronological order

from 1756 (Payne) to 1908, with index.

Lovell, Kenneth -- Draughts Books of the 20th Century, 1990, Damier Books, 91 pp., (81 pp. online, without illustrations), spiralbound, ISBN 095154330X

Published in a limited edition of 100 copies; out of

print and very rare. The author compiled it to update

Call's The Literature of Checkers.

The book contains 451 entries: some book dealers give reference numbers

from Call and Lovell

(a la Köchel) in their listings. It is now available

online, courtesy of the author, on Bob Newell's Checker Maven site.

North Carolina Checkers Association: Abbreviations & Definitions

contains assorted information on books and magazines, organizations,

computer programs, a few notable people, and a little bit of history.

There are quite a few books entitled The Game of Draughts,

with a subtitle giving more specific information (often the name of an

opening). Many authors also seem to feel that no book on

checkers is complete without some problems, perhaps some poetry, and

definitely The Laws of the Game.

Anglo-American Checkers

(Draughts)

Introductory Works

Atwell, Richard -- Scientific Draughts, 1905, J.A. Kear Jr., Bristol, 186 pp., hardback

Atwell was columnist for the London Daily News, and co-edited the original version of Kear's Encyclopaedia (two parts of which had already been published).

The first part of this remarkable book is a series of short essays on various

topics, including perhaps the first discussion of Three-Move Ballot

Restriction: "After all unsound openings have been eliminated, it will

be found that there are 218 absolutely sound Openings, containing

treasures compared with which all present published play pales into

insignificance." Atwell

is counting in an odd way, not counting exchanges as part of the three

moves (so he counts 11-15 24-19 15x24 28x19 7-11 as three moves), and

eliminating certain types of moves now understood to be playable (such

as 11-15 22-17 10-14, forcing an exchange from 7). Atwell gives a complicated nomenclature for the two-move

openings, using Switcher for 21-17, Choice for 22-17, Single for 22-18,

Cross for 23-18, Regular for 23-19, Double for 24-29, and Side for

24-20, but also using Repeat for imitated moves (10-14 23-19 he terms

Denny-Repeat), Exchange for replies which force a capture (11-16 23-19

is Bristol-Exchange), and Gambit for the two 21-17 replies which give

up a piece (9-14 21-17 is Double Corner-Gambit). A dozen playable gambits (giving up a piece for a positional advantage) are listed on page 31. The

middle part of the book gives 46 endings and over 250 additional

problems, with solutions. The section of Brilliant Games contains

100 games (many of them composed) with a diagrammed middle game

position from each, presented as a problem (also with solutions); some

of these are well-known traps. A bibliography lists over

230 publications, but giving only the author or title, city, and year of

publication.

Boland, Ben -- Checkers For The Millions, 1939, Boland,

Brooklyn, 36 pp., paperback

Basic lessons in the Dyke formation, traps and shots, and

endgames. Republished two years later as The Game of Checkers (see A.J.

Mantell below).

Call, William Timothy -- Ellsworth's Checker Book, 1899, Call, Brooklyn, 65pp.

Guide to openings and 11 basic positions, from an unpublished

manuscript by Charles Ellsworth. Some of the positions are

deeply analyzed, with tables of variations similar to those used for

openings. The last section of the book is a long essay by Call on

the relative merits of chess and checkers.

Chernev, Irving -- The Compleat Draughts Player, 1981, Oxford University Press, 314 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-0192175878

Guide for beginning and intermediate players, covering most

aspects of the game (except for two- and three-move restriction), with

hundreds of diagrams (readable although the publishers chose to print

with the pieces on dark squares). Chapter 6, Logical

Draughts, Move by Move, plays through two illustrative games with

annotations of every move. Chapter 12, 100 Traps in the Opening,

has examples from almost every traditional opening. There

are dozens of annotated games and problems, biographies of some notable

players, history, and a short bibliography. Surprisingly

uncommon and expensive for a comparatively recent book.

Grover, Kenneth M., and Tom Wiswell -- Let's Play Checkers, 1940,

David McKay, 1972, Tartan, 188 pp., paperback

Good introductory book. The game section, by Grover,

recommends that beginning players play the Cross opening as White

against 11-15, and the Double Corner 9-14 as Black. The

section on mid-game structures covers some opening traps and basic

landings. There is a section on basic endings and king endings,

and a selection of 100 problems.

Held, Lawrence -- Held's Guide to the Game of Checkers, 1935, David McKay, 104 pp., hardback

Beginner's guide, but with little instruction on general tactics

except a brief description of The Move. Example games are given

in the go-as-you-please openings, with some variations and light

annotation for what he calls the 25 Standard Openings. For the 16

Secondary Openings (including the 27-20 Second Double Corner and the

26-17 Single Corner) he gives only a sample game. The middle

section includes history, tournament formats, a brief description of

Spanish Pool (Polish Draughts on the 8x8 board), and some tricks and

puzzles. The last major section is a collection of 100 problems

with solutions. The bibliography on the last page is only a

listing of books, reiterating the section on Advanced Study on p.

61. On p. 58 he mentions Four-Move Restriction as "being

discussed", and calls Eleven Man Ballot "Not checkers in the accepted term".

Hill, James -- Hill's Pocket Manual, n.d., David McKay, 64 pp., paperback

Beginner's book with endgame positions, opening traps, annotated

games, and problems.

Hopper, Millard -- An Invitation to Checkers, 1940, Simon and Schuster,

190 pp., hardback, $2.50

Excellent introductory book covering tactics, openings, and

endgames. Also in paperback as How To Play Winning

Checkers, 1943, Pocket Books.

Hopper, Millard -- Win At Checkers, 1941, A.S. Barnes, 1956,

Dover, 109 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-486-20363-8, $2.50

Very elementary book in question-and-answer format.

On page 58 he slightly oversimplifies the openings by recommending

22-18 as White's best reply (or one of the two best) to every Black

opening except 11-15.

Hopper, Millard F. -- The Major Tactics of Checkers, 1934, New York, 32 pp.

Booklet based on a series of lectures given by Hopper on radio

station WNYC. Covers openings (including what Hopper calls

the Forcing System), problems, and sample games. Diagrams

are given only on the last page, which presents 10 problems.

Jordan, Bill -- How to Play Better Checkers: Applying Chess to Checkers, 2022, Jordan, 62 pp., paperback, $11.99

Print-on-demand booklet by a (chess) Federation Master and noted writer on chess, looking

at checkers from a chess-player's viewpoint (he uses algebraic

notation, and even chess kings

in the diagrams). Superficial coverage of basic tactical

elements, an unnecessarily long endgame with two kings vs. one, and one

poorly played example game.

Landry, T.A., and L. Stephens -- Draughts, An Introduction to

Championship Play, 1984, London Draughts Association, ISBN 0-9509762-0-2

MacIntyre, Charles Coughlin -- Million Moves of Checkers, Your Study Guide To Scientific Play, 2023, 279 pp., paperback, ISBN 979-8376864920, $15.95

Print-on-demand book by a Canadian enthusiast.

The publication date says 2023, but it was assembled over decades:

the section on openings only covers the 137 pre-170 openings; elsewhere he

refers to Ron King as the current World Champion, which places it no

later than 2014. Poorly organized: no index or real

table of contents, badly printed diagrams, and quite a few typos and

other minor errors (e.g. page 68 and 149 are the same; part of the opening table on p. 25 is

misaligned, making the names and moves match up

incorrectly). Still worthwhile, with useful

information on tactics, endgames, and openings. Many

anecdotes about players both famous and not, and a listing of 70 books

and magazines.

Mantell, A.J. -- The Game of Checkers, Learn To Play Expertly In Four Easy Lessons, 1941, Padell, 34 pp., cardboard cover

One bookdealer listing has Boland as co-author,

but my copy does not show this. Mantell bought the publishing rights to Checkers for the Millions from Boland. There are errors in placement of the arrows on the diagrams on page 16.

Mitchell, David A. -- Checkers, 1918, Penn, Philadelphia, 183 pp.,

hardback

General strategy, openings and traps, endgames (including Tregaskis' Draw), a selection of Brilliant

Games, and a selection of problems with solutions.

Patterson, W. -- How To Play Checkers, 1927, Haldeman-Julius, 64 pp. paperback

Number 1183 in the famous series of Little Blue Books. Not dated, but 1182 and 1184 both appeared in 1927. Elementary instruction: the author recommends a very limited opening repertoire, and only

the Old Fourteenth and Single Corner are covered in any

detail. None of the other six Black opening moves are even mentioned. The last 13 pages give 54 lines of the Old

Fourteenth and 63 lines of the Single Corner, in tiny type, using the

Alexandrian System (each variation in one

column). The author says not moving any of 1/2/3/6/7/10 in the opening will

produce a good game for Black (and 23/26/27/30/31/32 for

White): this is sometimes called the D'Orio triangle, but isn't considered a sound principle in general. Call lists several works from the 1870's by W.

Patterson: Lovell confirms that this is the same book as Patterson's The Game of Draughts from about 1872.

Payne, William -- An Introduction to the Game of Draughts, 1756, 67 pp.

The first book on draughts in English. 50 games with no

annotation except footnotes indicating a losing move (modern practice

reverses this, using an asterisk (star move) to denote the only move to

win or hold a

draw). Includes six critical draws, eight critical wins,

and 24 strokes. No diagrams except for a numbered

board. Among the openings which appear are Single Corner, Old

Fourteenth, Cross, Will o' the Wisp, Black Doctor, and White Doctor.

Game number 1 shows the famous Goose Walk trap in the

Single Corner opening.

People's Journal -- The People's Draughts Book, n.d., People's Journal, 40 pp.,

Elementary handbook assembled from articles in the Scottish weekly newspaper The People's Journal, with elementary positions, games in the standard openings, and opening traps.

Phillips, Barnet (The "Major") -- The Checker Primer, 1887, Excelsior, New York, 24 pp., $0.10

Very elementary guide, including basic rules, 13 critical

positions (without solutions), and five sample games and variations

from Sturges. Briefly mentions Polish draughts (wrongly stating

that one queen can always draw against three) and the Losing Game.

The word checkers only appears in the title of the book and as a

subtitle on the first page; everywhere else the term draughts is used.

Reinfeld, Fred -- How To Win At Checkers, 1957, Sterling, 1967,

Wilshire, 186 pp., paperback, $2.00

Solid introductory book by a writer best known for chess

books. Republished under different titles, including How To Play Top-Notch Checkers, but to my knowledge this is Reinfeld's only book on checkers.

Reisman, Arthur -- Checkers Made Easy -- 1959, Key Publishing, New York, 107 pp., paperback

Regarded as one of the best introductory books; recommended by Pask in Book 4 of Complete Checkers: Insights (p. 327) as the first book to read for beginners.

Ryan, William F. -- It's Your Move: A New Guide to the Game of Checkers, 1929, David McKay, 115 pp.

Early book by the future U.S. Champion. 50 problems

with solutions, and a section on two-move restriction, with sample

games for most of the openings (Ryan uses compound names).

Ryan, William F. -- Scientific Checkers Made Easy, Revised Edition, 1934, 1945, 1950, John C. Winston, 205 pp., hardback

About half the book presents example games with analysis; the

remainder consists of problems, starting with what Ryan calls the Ten

Major Positions (starting with the standard four, and ending with

a three kings vs. two endgame). Diagrams printed in black and red.

Smith, Erroll A. -- The American Checker Player's Handbook, 1926, 1931, John C. Winston, 160 pp., hardback

Elementary guide with opening analysis, including the four barred openings (over 20 pages on the Barred Dundee),

transpositions, the Move, and standard positions. Diagrams

in red and black. Available at Google Books, but the PDF is missing the two-page index (viewable at Internet Archive).

Spayth, Henry -- Checkers for Beginners, Revised Edition, 1927, Regan,

86 pp., paperback

The Move, Critical positions, names of the openings, and sample games.

Spayth, Henry -- The American Draught Player, 6th edition, 1860, Dick & Fitzgerald, New York, 308 pp., hardback

Noted early American guide, including 17 openings and 1465

variations, 21 endgames and 56 variations, and 78 critical

positions. The Theory of the Move and Its Changes describes

opposition in detail, with ten diagrammed examples.

Sturges, Joshua -- Guide To The Game of Draughts, With Critical Situations, 1800, 53pp.

Collection of 54 games and 140 critical positions, expanding on

the work of Payne. The Old Fourteenth opening is named after its appearance as game number 14 in

both Payne and Sturges, although those books both give the move order

11-15 22-17; 8-11 17-13; 4-8 23-19. In 1808 Sturges published

a collection of problems, mostly from the 1800 edition, with full

diagrams printed in black and red, and expanded solutions.

Sturges's guide was revised and expanded

many times, notably by:

(1) George Walker in 1835, 87 pages, with 69 games and 150 positions; this was reprinted in Bohn's 1850 Handbook of Games.

(2) R. Martin in 1858, about 106 pp., with similar contents to Walker,

plus a short section on 10x10 Polish Draughts with two sample games,

and a brief outline of the Losing Game. This was the first

American edition, and the first to give an index of opening

names. Some of the games are still being presented

with White moving first: Game 68, a Second Double Corner, starts 22-18

9-14 18-9 5-14 instead of 11-15 24-19 15-24 28-19.

(3) Julian Darragh Janvier in 1881, 152 pages, with 20 games

showing 20 openings, and 172 critical positions, plus corrections to

earlier editions and other sources; the section on Polish and Losing

Draughts is omitted. This is much better organized

than earlier editions: Janvier has converted all of the games to Black

moving first, labeled them with opening names, and sorted them neatly

into separate columns for each variation, with sources for each

line. He uses * to denote improved moves, not necessarily star moves as understood today.

(4) J.A. Kear in 1895, 268pp., by which time it contained

example games for 27 different openings with 1466 variations, and over

200 positions with solutions. Kear also includes short

appendices giving the rules for five regional variants (Turkish,

Spanish, Polish, German, and Italian); these were expanded in the 1904

edition. Kear was co-author of the Encyclopaedia of Draughts

(see below in Openings); again, I don't know why Kear spent time doing

a second revision of Sturges in 1904 when he had already published two

parts of the Encyclopaedia).

Sweet, I.D.J. -- The Elements of Draughts, or Beginners' Sure Guide, 1859, 1872, De Witt, New York, 108pp.

Early American book by the draughts editor of the New York Clipper, the

first U.S. newspaper to feature a checkers column. Elementary guide

with the basics of endgames, openings, "the move" (on which the author

spends 17 pages, without a single diagram), and a collection of sample

games.

Trott, George E., ed. by E.C. Whiting -- The Clapham Common

Draughts Book, 1947 (unpub.), 1966, 1973 (English Draughts

Association), 2014 (PDF), 57 pp.

Beginner's guide to tactics, with emphasis on visualizing them in play. Electronic reproduction (63 pp.) with corrections and full-color diagrams by Mel Tungate.

Walker, Walton W. -- "Inside" Checkers, 1922, David McKay, Philadephia, 203 pp.

29 games and 36 problems, annotated almost move by move. Many traps are described.

Tom Wiswell was a champion player, noted problemist, and prolific,

best-selling author. He gave the 11-15 opening the name Old Faithful in Learn Checkers Fast.

Wiswell, Tom -- Learn Checkers Fast, 1946, David McKay,

1972, Tartan, 208 pp., paperback, $1.95

Good beginner's guide, including a section on the most

common openings, ratings for all 137 three-move ballots (including

example lines for the most critical ones), traps, problems, basic

endgames (The Golden Dozen [not the formerly barred openings]), and a detailed glossary. Available at the Internet Archive.

Wiswell, Tom -- Checkers In Ten Lessons, 1953, 1959, A.S. Barnes,

126 pp., hardback, $2.95