Index and Resource

Guide to Abstract Games

Compiled by Michael Keller

In this booklet, we will use a common definition of abstract games as two-player games of perfect information. Some

of the material herein appeared in WGR. Some major

game families (e.g. checkers, reversi) have their own dedicated guides.

Table of Contents

Mancala Games

Alignment Games

Placement Variants

Movement Variants

Delta

Territorial Games

Go

Amazons

Other Games

Fanorona

Bibliography

Individual Games

Mancala

Hoyles

Other

Go

Magazines

Mancala Games

Mancala is a large family of folk games sometimes called "pit and

pebble" or "count and capture" games. They are played on boards consisting of two or

more rows of cups, into which some number of stones are placed initially. Usually there are two larger pits, called storehouses,

at the ends of the board, which are used only for storing captured stones

(each player uses the storehouse at their right). A move consists

of taking all of the stones from one of the cups on your own side, and sowing

them anticlockwise, one stone into each of the succeeding cups,

continuing into the opponent's cups if there are enough stones in

hand. Depending on the variant, stones are captured

according to a particular set of rules. A large group of games,

of which Wari is the best

known, are played on a 2x6 board starting with four stones in each

cup. In Wari, if the last stone sown lands in one of the

opponent's cups so as to end up with two or three stones, those stones

are captured, along with any one or more consecutive pits prior to the

last which also contain 2 or 3 stones.

Alignment Games

The objective is to align some number of pieces in a line or some other

configuration. Roughly divided into placement and movement

families.

Placement Variants

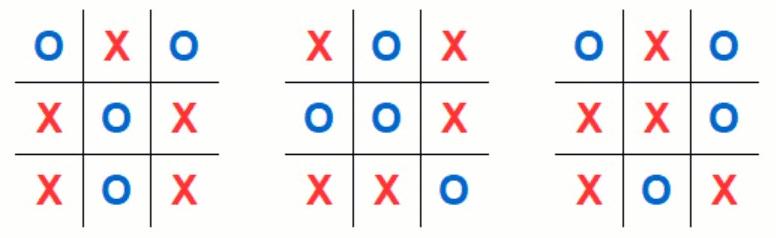

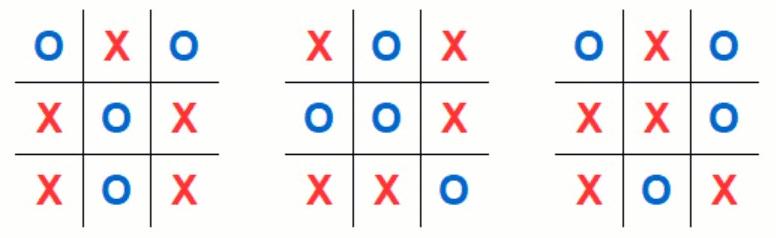

The three draw positions in Tic-Tac-Toe (X moves first)

Tic-Tac-Toe (Noughts and

Crosses) is probably the simplest alignment game, frequently played by

children as a pencil-and-paper game. Players play

alternately on a 3x3 board, trying to get three of their pieces in a

line (horizontally, vertically, or along either long diagonal).

With best play it is always a draw; every drawn position can be reduced

to one of three positions by reflection and rotation (diagram

above). The three-dimensional

version on a 3x3x3 board is an easy win for the first player, playing

in the middle of the second level. The 4x4x4 game (marketed many

times as Qubic and other names) is much more strategic, though Owen Patashnik proved in 1980 that the first player has a forced win. There are many other variants, including Ultimate Tic-Tac-Toe,

played on a 9x9 grid divided into nine normal 3x3

boards. A version sometimes called Super Tic-Tac-Toe

is played on a 4x4 board, with a win for forming four in a row in any

direction, a 2x2 square, or (very unlikely) all four corners (it's

probably a draw with best play, but there are several traps).

A

popular commercial variant is Connect Four,

which is a 7x6 form of what is

sometimes called Vertical Tic-Tac-Toe: a piece may be played into any

column, but drops to the lowest empty space in that column. Connect Four was solved in 1988 by James Dow Allen; it is a win for the

first player, but only if the first move is in the center column. John Tromp has computed the number of legal positions

at each point in the game (the total is about 4.5 trillion), and the

result on other sizes of boards. There are rumors of early

folk versions of the game, including a version called The

Captain's Mistress, supposedly played by Captain Cook, and a game

called Four Balls, owned by the historian R.C. Bell, which he estimates

was from the early 20th century. None of the stories have

been confirmed; the website Tradgames

has a history of some of the commercial variants, including several

patents. 4x4x4 Tic-Tac-Toe has also been manufactured as a vertical variant.

By tilting a large board (say 6x6 or 7x7) at a 45 degree angle, and

having two solid sides at the lower left and right, and two open sides

at the upper left and right, and allowing pieces to be placed in any

open diagonal, it is possible to play a different variant which might

be called Gravitational Tic-Tac-Toe (I think this has been proposed, but the only reference I can find is a recent iPad app).

The first piece, no matter where played, falls to a1; the second will

go to a2 or b1 (the player who drops a piece can choose in which

diagonal direction it slides when it hits another piece). I

don't

know how this would work in practice. Other variations are

possible: what if you could insert a piece at the bottom and push a

whole row?

Go Moku and Renju

Go-Moku (often called Go-Bang

in older accounts in Western game literature) is essentially an

extended form of tic-tac-toe, dating from 18th century Japan, where it

was played with Go stones on the points of a standard board

(19x19). Nowadays the standard board is 15x15; players play

stones alternately, trying to get five in a row orthogonally or

diagonally. Black plays first, and has a huge

advantage (L. Victor Allis proved in 1994 that Black has a forced win

in the unrestricted game). Various schemes have been devised to minimize Black's advantage; the most common version is called Renju,

which places restrictions on Black only: Black cannot place a stone

which forms two simultaneous open threes (three stones in a row open at

both ends) or two simultaneous fours (four in a row, blocked or not),

and cannot win with an overline (a line of six or more

pieces). Black can force a win in Renju by forming a

simultaneous four and open three, which is legal. In

tournament play, complex rules have been introduced to add variety to the opening play, in a manner similar to three-move ballots in checkers. There is a Renju International Federation, formed in 1988, which governs international competition, including a World Championship.

Ninuki-Renju is a variant of

Renju with the addition of custodian captures: a stone placed so as to

sandwich two opposing pieces between it and a friendly stone captures

the two stones. A player can win either with five in a row

as usual, or by capturing 10 stones (5 pairs). The commercial

game Pente

(Gary Gabrel, 1977) is a variant of Ninuki-Renju on a 19x19 board with

none of the move restrictions of Renju. It also has a

strong advantage for the first player, and has itself spawned variants,

including Keryo-Pente, a

variant by Rollie Tesh (Pente World Champion), which also allows three

stones at a time to be captured, and allows a player to win by

capturing 15 stones (or five-in-a-row as usual).

Movement variants

Nine Men's Morris

Dating to the Roman Empire, Nine Men's Morris is also called Merelles, Mill, and many other names; Shakespeare may have coined the term Morris in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

It is played on a board of 24 intersections on three consecutive

squares, with players having nine pieces each, attempting to get three

in a row (a mill) along one of

the sides of the squares, or the lines connecting the three squares

(each successful three allows one opposing piece to be removed).

Once each player has placed nine pieces, pieces move along lines from

one intersection to an adjacent one. The game was proven to

be a draw with best play by Ralph Gasser in 1996. As usual there are dozens of variants, ranging from 3 to 12 pieces per side.

Kensington -- invented by Brian Taylor and Peter Forbes, 1979

Alignment game, in the Nine Men's Morris family, on a

board with seven hexagons connected by squares and

triangles. [Technically, this is the (3.4.6.4) Archimedean tiling,

which Andy Liu used to design his multiform puzzle set The Birds and

the Bees.] The game was heavily publicized when it was first

published, with celebrity endorsements, and made an initial splash (the

Washington Post breathlessly called it "Britain's biggest export since

the Beatles"), being nominated for the 1982 Spiel des Jahres

award. It's mostly forgotten today. Christian

Freeling designed his game Lotus using the same board (see

Schmittberger for more details).

Delta -- invented by Erich Brunner, first published 1975 by Otto Meier Verlag

An elegant 5x5 alignment game invented in the 1930's by the Swiss chess

problem

composer Erich Brunner. (The game was named Delta because the

pieces are triangular.) A WGR correspondent, Paul Gabriner,

sent me the rules,

and I introduced the game into The Knights of the Square Table,

where it proved quite popular (also in AISE). Each player has

nine pieces. White moves first. On their first moves, each player

drops a new piece to any square. Each move thereafter

consists of sliding a piece at least two squares in any direction (over

vacant squares only), and dropping a new piece on the last square the

moving piece passed over. (To diminish the advantage of

moving first, Black may choose drop a piece anywhere on their second

move). Once all nine pieces have been dropped, a move

consists of a slide, then shifting another piece to the last square

dropped over (many games never reach that phase). The first player to form four in a row in any

direction, or to block their opponent so the opponent has no legal

slides, wins.

The notation is normal algebraic; drops are indicated by a single

square, slides by two squares (the location of the new piece is

automatic and is not noted); starting at move 10, the third square

indicates what piece is lifted to drop on the last square passed

over). For example, c3a3 moves a piece and drops

automatically at b3; a3a1c4 moves a piece, lifts the piece from c4, and

drops it at a2. Symbols: + indicates a threat to make four in a row; #

indicates a win by four in a row; @ indicates a win by stalemate; *

indicates the only move that does not immediately lose (adopted from

checkers).

Strategy: Early play usually attempts to make four in a row threats, easier when you control the center. But

there are quick opening traps on the outer lines: 1 a5 c3 2 a5e5 c4??

loses to d5a5; Black cannot prevent e5c5#. The longer a game goes, the more likely wins will be by stalemate

instead of four in a row; pieces in the central 3x3 area are easier to

block when the board is crowded with the maximum 18 pieces.

Here is an example game, showing some of the tactical possibilities, from the first NOST postal tournament in 1991,

DE-T91.

White: Al Dawson Black: Michael Keller (notes by MK)

1 c3 c5

2 c3a3 c5c2

3 b3d5 c2a4

4 d5d1 c3a5

5 d2d5+ {d1d3 next makes four} b4d2+

6 d5b5 c3c1 (to protect against c5e5+; b3b1 loses to dlb3; White cannot stop c5e5 followed by a3c5)

7 d4a1? [I believe Black can force a complex win here with d4b2,

threatening c5e3+ as well as double check by c5e5++. White can only

block both threats by d2d5*, the best line thereafter seems to be 8

c3e1 c2e4 9 ele3+ a5c3* <if ...c1c3, a3a1e3 wins by stalemate> 10

a3alc4 d3b1(any) 11 e2c4a1+]

7...d2b4+ (threatens c2e2# or c1e3#)

8 Resigns (d1d3 allows c1e1#).

I wrote probably the first computer version of Delta in late 1991, in Fortran. It went through several versions, before being

converted into a Visual Basic version.

Territorial Games

Go

Unrelated to Go-Moku, Go is widely regarded as the deepest strategy

game in the world, despite generally simple rules (the rules actually

have great complexity when dealing with (rare) potentially repeated

positions; see for example Molasses Ko and Moonshine Life). In simplest terms, two players (Black and White) play

stones alternately on a board of 19x19 intersections (points), trying to surround more territory than the opponent. Single stones or groups of connected stones can be captured by completely surrounding them so that there are no empty points (liberties)

adjacent to any of the stones. Captured stones are removed

from the board, and used at the end of the game to fill in some of the

opponent's territory. The bibliography lists a number of

guides from the most basic to the most complex strategy.

Hundreds of opening patterns (joseki) have been catalogued and studied.

El Juego de las Amazonas (The

Game of the Amazons) by Walter Zamkauskas

The Game of the Amazons (or

simply Amazons) is an abstract game of territory for two players,

played on a 10x10 board (a checkered board makes it easier to visualize

diagonal moves). Each player has four amazons, which move like chess

queens : any number of vacant squares in a straight line --

orthogonally or diagonally. After it moves, an amazon must fire

an

arrow in the same manner from its landing square (one or more vacant

squares orthogonally or diagonally). The square where the arrow lands

is then marked with a poker chip or other counter to indicate it is

blocked (in the computer version blocked squares are colored dark red).

No amazon or arrow may move into or through a blocked square. The

starting position is shown above left. White moves first, moving one

amazon and firing an arrow with that amazon (above right).

The players

alternate moves, and the player last able to make a move

wins. Draws are impossible, and the game cannot last more

than 46 moves. In practice, in most games, the territory is

walled off and the status of every empty square is known earlier than

46 moves, and territory can simply be counted.

El

Juego de las Amazonas

was invented in 1988 by Walter

Zamkauskas of Argentina, and first published (in Spanish) in issue number 4

of the puzzle magazine El Acertijo in December of

1992. In 1993, I informally introduced it to the postal gaming club The Knights of the Square Table, where it gained

immediate popularity. An authorized translation was published in January 1994.

The first international match was a friendly team match, played by fax between

Argentina and the United States in 1994-1995; the six games were split

3-3. In early 1994, I wrote what I believe was the first computer version, in Fortran with a simple keyboard interface. It had a weak

computer opponent. The Windows version, from which the screenshot

diagrams above are taken, is a slightly later development of the same program, now

written in Visual Basic.

Amazons became an event in the Mind Sports Olympiad

in 1997, and in the 5th Computer Olympiad in 2000. An introduction by Paul Yearout appeared in Abstract Games 16 (2003, pp. 12-13). A video

introduction to Amazons with Dr. Elwyn Berlekamp can be found on YouTube.

A number of very strong programs have been written to analyze and play

Amazons, and mathematical papers have been published by, among others, Hensgens (2001), Müller and Tegos (2002), Lieberum (2005), Kloetzer et al. (2008), and Song and Müller (2014). However, the game has been solved only on very small boards.

A number of variants have been proposed, among them Phil Cohen's Non-Parthian Amazons,

in which amazons may not fire directly behind them after moving (among

other effects, this nullifies the last square in each territory), and

Fergal O'Hanlon's Centaurs, in which amazons may fire from any square along their movement path (including the starting square).

El Juego de las Amazonas (The Game of the Amazons) is a

trademark of Ediciones de Mente.

Other Games

Fanorona

Dating back centuries, and known as the national game of Madagascar, Fanorona has two unusual capturing

methods called approach and withdrawal (the latter inspired one of the

pieces in Robert Abbott's chess variant Ultima).

It is played on the intersections of a 9x5 board (see the empty board

and the initial arrangement of pieces above), which probably originated as a doubled Alquerque board

(there is also a smaller version, played on the usual 5x5 Alquerque

board). Each move consists of shifting a piece in any orthogonal

or diagonal direction along a marked line (e.g. a1b2 is legal, but not b1a2). A move may capture opposing pieces along its line of movement in one of two ways:

(a) Approach capture: if the

piece moves next to an opposing piece along its line of movement, it

takes that piece and any adjacent opposing pieces along the line of

movement. For example, in the initial position, d2e3 captures f4

and g5.

(b) Withdrawal capture: if the

piece moves directly away from an opposing piece or line of pieces

along its line of movement, it captures all of them. For example, if

White (from the initial position) plays e2e3, capturing e4 and e5,

Black may reply f4e5, capturing g3, h2, and i1.

A move may not capture by both approach and withdrawal; if both are

possible, the moving player must choose which capture to make. If White

(from the initial position) plays d3e3, he may capture f3 (by approach)

or c3 (by withdrawal), but not both. A player must make a

capturing move on each turn if possible, but may choose any available

capture or series of captures; a non-capturing move (paika)

is only allowed if no captures are available. After making a

capture, if the moving piece may move along a different line and make

another capture, it may do so on the same turn, and may continue making

further captures as long as it is able. These additional captures are

not compulsory; a player may stop at any time after making at least one

capture. Each capture must involve a change of direction, and may

not reverse direction along the same line just traversed. A piece

making a series of captures may not return to its starting point or any

other point it occupied during the turn. Captured pieces are removed

after each move in the series, so a piece making a series of captures

may later move to a point which was originally occupied by an opposing

piece. The object is to capture all of the opponent's

pieces; a draw may be agreed if neither player can force any further

captures.

Notation: White opens the game with d3e3:c3. Black may play

d4d3:d2,dl; d3c3:e3; c3d2:el; d2e3:cl (or may stop anywhere during the

series of captures). Since a capture always captures a complete string,

there's no need to write all of the pieces taken. Just indicate

whether the capture is by withdrawal (-) or approach (+), and the

number of pieces taken. For example, the capture just mentioned is d4d3(+2)c3(-1)d2(+1)e3(-1).

Example

moves

A lost position for White

In the diagram above left, either player has 7 initial

captures if it is their turn to move. White may capture b2b3(+1),

c3d2(-1), c3d3(+3), e1f1(-1), e1e2(+1), e1f2(+1), or h4i5(-1). If

White captures e1f1(-1), they may not continue with f1g1(+1), as

another capture on the same turn must change direction. They may,

however, continue with other captures: the multiple capture

e1f1(-1)f2(+1)g1(-1)g2(+1) is one possibility; others are

c3d3(+3)d2(+1), or c3d2(-1)d3(-1). Note that White may not return

to c3 in either case. White may not make a noncapturing move, such as

e1d2. If it is Black's turn, Black may capture b4a5(-1) (this

does not capture el because of the empty point at d2), b4b3(+1)

[continuing a3(-1) if desired], d1c1(-1) [continuing c2(+1) and then

d2(-1) if desired], e3d3(+1), e3e2(+1), g3f2(+1), or g3f2(-1) [if Black

plays g3f2, he must capture either el or h4, not both, and may not

reverse direction on the same turn to capture the other]. Black

may not make a noncapturing move, such as f3f2.

Sample Game: The following game was played in a 1993 NOST postal tournament.

White: Michael Keller Black: Aldo Kustrin

1 f2e3(+2) d5d4(+3)

2 f1f2(+3) d4c5(-3)

3 e2e3(+2) c3d2(+1)e2(-3)e1(-1)d1(+3)

4 b3b2(-2)c1(-1)b1(-1) c4c3

5 Resigns (White's position appears demolished after either capture by g3; position above right)

{Zillions of Games found quick wins after g3f3(-1) g4g3(+1)h3(-1), or after g3f2(-2) g4g3(+1)f4(-2)f3(+1).}

[Adapted from the official Knights of the Square Table

(NOST) rules for postal play, by Michael Keller and Philip Cohen,

copyright ©1988. The diagrams were produced using the Malagasy True Type font produced by Alpine Electronics.]

A traditional Malagasy match consists of a series of 10 games

played, with each of the five openings played once by each player. A

player losing a game must play a punishment game called a vela (Malagasy for debt), in which the winner sacrifices 17 pieces before continuing play normally. The five openings (riatra) are: vakiloha e2e3(+2), havanana f2e3(+2), ilaihavia d2e3 (+2), fohy d3e3(+1), and kobaka d3e3(-1). The board is sometimes set up in the mirror image of the diagram above.

In 2008, a team of Dutch researchers showed that Fanorona is a draw

with best play, if White plays the havanana or fohy openings (the

authors believe that vakiloha is a loss for White, but were unable to

establish a result for the other two openings). In 2012,

there was a new flurry of interest

in Fanorona, when it was introduced as a minigame in the popular video

game Assassin's Creed III.

Bibliography

Prices, where given, were at the time of publication.

Many of these books are out of print. Pictured books are particularly recommended.

Individual Games

Allen, James Dow -- The Complete Book of Connect 4, 2010, Puzzlewright

(Sterling), 262 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-1-4027-5621-4, $14.95

Detailed guide to Connect Four, including tactics, strategy, openings, and variants. Out of print and rare.

Browne, Cameron -- Margo Basics, 2012, Lulu, 172 pp., paperback

Game in the Go family, played on a 7x7 board with marbles that can be stacked upwards.

Scarne, John -- Scarne on Teeko, 1955, Crown, 256 pp., hardback

Alignment game played on a 5x5 board.

Tesh, Rollie, and Tom Braunlich -- The Megiddo Book, 1985, Global Games, 67 pp., paperback

Alignment game played on a circular 6x6 board.

Fanorona

Chauvicourt, J. and S. -- Fanorona, The National Game of Madagascar,

International Fanorona Association, 1972, 1984, 44pp., paperback

Rabeony, Ernest, tr. by Leonard Fox -- Fanorona, The Ancient Boardgame

of Tactical Skill from Madagascar, 1993, International Fanorona

Association, c. 141 pp., ISBN 0-932329-02-0

Both are out of print, but Rabeony's book is available in a Kindle edition (though without diagrams). It includes detailed analysis of openings, endgames, and vela.

Hex

Browne, Cameron -- Hex Strategy, Making the Right Connections, 2000, A.K. Peters, 363 pp., paperback, ISBN 1-56881-117-9

Definitive guide to the classic connection game, invented by Piet Hein

(of Soma fame) and introduced in 1942. Covers many aspects

of strategy in the standard 11x11 game, plus problems and sample

games. Illustrated with hundreds of high-quality

diagrams. Includes a detailed bibliography, and section on

variants and related connection games.

Kensington

Hiron, Alan -- The Official Book of Kensington, 1981, Contemporary, 94 pp., ISBN 0-8092-5487-5, $3.95

Johnson, J. Robert, and Mason A. Clark -- The Official Guide to Winning at Kensington, 1983, Tribeca, ISBN 0-943392-33-0

Pente

Braunlich,

Tom -- The Official Book of Pente, The Classic Game of Skill, 1983,

Contemporary, 83 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-8092-5522-7, $7.95

Braunlich, Tom -- Pente, The Classic Game of Skill, Strategy Book I, 1980, Transcript, 66 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-9609414-0-1

Braunlich, Tom -- Pente, Strategy: Book II, Advanced Strategy and

Tactics, 1982, Pente Games, 110 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-960-94141-X

Braunlich, Tom -- Pente Strategy, 1984, Warner, 132 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-446-38236-1 (expanded version of Book II above)

Renju

Sakata, Goro, and Wataru Ikawa -- Five-In-A-Row (Renju), For Beginners to Advanced Players, 1981, Ishi Press, 153 pp.

Mancala

3M Corporation -- Oh-Wah-Ree, 1966, 3M, 11 pages, booklet

One of 3M's series of Bookshelf Games. Describes seven forms of

mancala; the locations where each game is played are given, but not the

native names. Full or partial sample games are gives for most of the

variants (the last variant, Grand Oh-Wah-Ree, is a meta-variant in

which pits can be captured; it can be played with most of the other

variants).

Chamberlain, David B. -- How to Play Warri: The Caribbean Oware Mancala

Game, 2nd Edition, 1984, 1991, 2017, Purple Squirrel, 58 pages,

paperback, $8

Strategy for one of the most popular variants (usually spelled

Wari). The most detailed strategy discussion I have seen

for any mancala variant.

Russ, Laurence -- Mancala Games, 1984, Reference Publications, 111 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-917256-19-0, $14.95

Russ, Laurence -- The Complete Mancala Games Book, 1995, 2000, Marlowe, New York, 141 pp., paperback, ISBN 1-56924-683-1, $14.95

Description of dozens of regional games from Africa and Asia, including

games with two, three, and four rows of holes. Includes a

five-page bibliography. No strategy discussion.

(Various authors) -- Count and Capture, The World's Oldest Game, 1955, Cooperative Recreation Service, 40 pp., paperback

Describes about ten regional variants.

Hoyles and General Games Compendia

Ainslie, Tom -- Ainslie's Complete Hoyle, 1975, Simon and Schuster, 526 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-671-24779-4, $11.95

The author was an expert in horserace handicapping, but sad to

say, not in games in general. The coverage of most games is

superficial, and the section on gambling problematical: he basically

equates card-counting in blackjack to theft, and spends several pages

on betting systems (martingales and the like) that are mathematically

unworkable.

Bell, R.C. -- The Boardgame Book, 1979, Knapp (Viking), 160 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-89535-007-6, $35.00

Oversized book in a slipcase with eight enormous boards printed

in full color on glossy paper, plus a sheet of tokens. Many of

the games, unfortunately, are simple roll-and-move games with little

strategy.

Gibson, Walter -- Family Games America Plays, 1970, Barnes & Noble, 275 pp., paperback, ISBN 978-0064633765, $2.50

Chapter 3, Board Games, pp. 45-100, gives brief introductions to

checkers, giveaway checkers, chess, box the fox, reversi, halma, and

Chinese checkers.

Goren, Charles H. -- Goren's Hoyle Encyclopedia of Games, 1950, 1961, Greystone Hawthorne (Chancellor Hall), 656 pp., hardback

McConville, Robert -- The History of Board Games, 1974, Creative

Publications, Palo Alto, CA, ISBN 0-88488-009-5, paperback

Survey of board games, classified into categories.

Many boards are illustrated with large diagrams which can be reproduced

and played on. Useful survey of capturing methods, and

instructions for constructing quality woodengame boards.

Mohr, Merilyn Simonds -- The New Games Treasury, 1997, Houghton Mifflin, 432 pp., paperback, ISBN 1-57630-058-7, $23.00

One of the finest modern compendia, carefully researched and

well written, illustrated with elegant monochrome drawings by Roberta

Cooke. Chapter 4, Sowing Seeds: Mancala Games, is

particularly good, covering 14 different forms of the game.

Pritchard, David -- The Family Book of Games, 1983, Michael Joseph, 208 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-7181-2356-5, £9.95

The first chapter, Table and Strategy Games (pp. 9-73), is

devoted to abstract board games (except for the race game Nyout),

including mancala, nine men's morris, draughts, fanorona, reversi,

Laska, chess, xiang qi, shogi, hasami-shogi (played on a 9x9 shogi

board but unrelated to the chess variant), go, go-moku, and

renju. Beautifully illustrated.

Pritchard, David -- Five-Minute Games, 1984, Bell & Hyman, 64 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-7135-1494-9, £0.99

Over 60 games, a mixture of pencil and paper, dice, and other

games. Among the unusual abstract games included are Alvin

Paster's Pasta (which combines Laska and checkers), Bagh Chal (a Fox and Geese variant from Nepal, played on an Alquerque board), Scott Marley's Archimedes (with an unusual capturing method), and Robert A. Kraus' Neutron.

Provenzo, Asterie Baker, and Eugene F. Provenzo -- Play It Again,

Historic Board Games You Can Make and Play, 1981, Spectrum

(Prentice-Hall), 243 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-13-683359-4, $7.95

Chapters on Nine Men's Morris, Alquerque (including Fanorona),

Halma, Mancala, Queen's Guard (or Agon, a Victorian game on a hexagonal

board), Chivalry (the original version of Camelot), Go-Bang (Go Moku),

Seega, Fox and Geese, Draughts, and Reversi.

Sackson, Sid -- The Book of Classic Board Games, Klutz Press, 1991, 43 pp., ISBN 0-932592-94-5, hardback, $15.95,

Klutz Press is a publisher of a wide range of how-to

books, dealing with games and other recreations (juggling, music,

etc.). This book is a collection of "the best fifteen board games ever

invented". Actually, the selection is limited to games played

with

simple pieces and rules -- e.g. there are no versions of chess

included. The boards for the fifteen games are printed on the pages of

the book, which opens flat to form a playing surface. Also included are

a set of thirty black and white stones and a pair of dice, in zippered

pockets attached to the book. Each game includes rules, brief history,

and hints for strategy. There are some errors and omissions,

e.g.: The rules for captures in Fanorona are incorrect (first captures

are mandatory, multiple captures are not); Hex was actually invented by the great Piet Hein

(inventor of Soma among others) prior to its

reinvention at Princeton (that graduate student, by the way is John Nash (A Beautiful Mind), one of the greatest 20th century mathematicians); the mancala version described is NOT Wari,

but a simpler game often called Kalaha. A serious complaint

about the book is that many of the games are renamed for reasons which

escape me. On the whole it's somewhat disappointing: it would be good for

introducing children to some of the great games if it were more accurate. The abstract games included are checkers (8x8

Anglo-American), 4x4x4 tic-tac-toe, Asalto, Surakarta, Hasami Shogi

(unrelated to Japanese chess except that the board is 9x9), Go (9x9),

Hex, Brax, Halma (the 14x14 square forerunner of Chinese Checkers),

Fanorona, Blue and Gray (published by Sackson in A Gamut of Games),

Mancala (Kalaha), and Nine Men's Morris. But even experienced game

players may find several games they have never played before.

Scarne, John -- Scarne's Encyclopedia of Games, 1973, Harper and Row, 628 pp., hardback, ISBN 06-013813-0

Other Collections

Angiolino, Andrea -- Mind-Sharpening Logic Games, 1995, 2003, Sterling, 96pp., paperback, ISBN 1-4027-0412-7, $6.95

Bell, Robbie, and Michael Cornelius -- Board Games Round the World, A Resource Book for Mathematical Investigations, 1988, Cambridge University Press, 124pp., paperback, ISBN 0-521-38625-X

Includes a section on mancala games, and a variety of simple

board games. Also covers the complex medieval board game

Rhythmomachy.

Berlekamp, Elwyn, John H. Conway, Richard K. Guy -- Winning Ways for

your mathematical plays, Volume 1: Games In General, 1982, Academic

Press, 426xi pp., paperback, ISBN 0-12-091101-9

Berlekamp, Elwyn, John H. Conway, Richard K. Guy -- Winning Ways for

your mathematical plays, Volume 2: Games In Particular, 1982, Academic

Press, pp. 427-850xix, paperback, ISBN 0-12-091102-7

Definitive work on the mathematical foundation of games of

strategy, including too many abstract board games to list here.

Cornelius, Michael, and Alan Parr -- What's Your Game?, A Resource Book

for Mathematical Activities, 1991, Cambridge University Press, 124pp.,

paperback, ISBN 0-521-35924-4

Freeman, Jon -- The Playboy Winner's Guide to Board Games, 1979, Playboy, 286 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-872-16562-0, $2.50

Collection of descriptions of commercial games, including light

strategy. originally published in 1975 as A Player's Guide to Table

Games (Stackpole, 285 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-8117-1902-2), under the

pseudonym John Jackson.

Chapter 7, Abstract Games, pp. 119-169,

covers:

(1) Oh-Wah-Ree, Avalon Hill's commercial variant of Wari, one of the best-known mancala games

(2) Go-moku, including commercial versions Qubic (Parker Brothers) and Five Straight (Skor-Mor)

(3) Twixt, a renowned connection game by Avalon Hill

(4) Go, the board game invented in China as Wei-Chi

(5) Othello, the commercial version of reversi published at that time by Gabriel (not in the original book)

(6) Chinese Checkers (which is neither), a variant of Halma on a star-shaped board

(7) Ploy, a loose chess variant by Avalon Hill for two or four players

(8) Smess, a chess variant by Parker Brothers which has also appeared as All The King's Men and Take The Brain

(9) Master Mind and Black Box, deductive games which are not abstracts

by the definition used in this booklet. The original book left

these out, adding a few more games.

Parlett, David -- The Oxford History of Board Games, 1999, Oxford University Press, 386 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-19-212998-8

Wide-ranging survey of board games, including chapters on chess variants, checkers variants, mancala, and others.

Pritchard, David, ed. -- Modern Board Games, 1975, Games & Puzzles, 144 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-86002-059-2, £3.95

David Wells describes Twixt in Chapter 7 (pp. 92-101) and Ploy

in Chapter 11 (pp. 123-132). None of the other games are

abstracts as defined here (they have either chance elements or hidden

movement).

Sackson, Sid -- A Gamut of Games, 1969, Castle Books, 210 pp., hardback, $6.95

(Republished in paperback, 221 pp., 1982, Pantheon, ISBN 0-394-71115-7, $5.95; 1992, Dover, ISBN 0-486-27347-4, $6.95)

Legendary collection of games, 22 invented by the author; the

rest are by some of his fellow inventors, or little-known historical

games. Lines of Action, by Claude Soucie, one of the most

renowned abstract games, was first published here. Other

abstracts include Cups. a modern mancala variation by Arthur and Wald

Amberstone; Crossings, by Robert Abbott, which was later expanded into

the successful commercial game Epaminondas; and Focus, by Sid Sackson,

also commercially published. Dover's 2011 paperback edition is still in print.

Salaamallah the Corpulent -- Medieval Games, 1982, Third Edition, 1995, Jeff DeLuca, 203 pp., spiral-bound

Comprehensive survey of traditional board games, including

sections on regional chess variants and mancala games. Widely

sold at Renaissance Festivals. It includes a section on the

medieval board game Rhythmomachy, including five different versions of

the rules. The games are a somewhat mixed bag, but there

are many fine ones here, along with ample historical notes. Highly

interesting reading, recommended especially to anyone interested in the

history of games.

Schmittberger, R. Wayne -- New Rules For Classic Games, 1992, John

Wiley & Sons, 245 pages, paperback, ISBN 0-471-53621-0, $9.95

Written by a long-time inventor and collector of games, and a regular contributor to Games Magazine.

This is a collection of well over 150 games and game variants; a few of

them should be familiar but most of them will be new to readers.

The emphasis is on board games -- there are very good sections on

variants of checkers, and chess. (More details on the checker

section in the checkers article). Coverage of certain areas is

fairly light (card games,

mancala, reversi) or absent (Diplomacy, pure dice games), but there is

quite a bit of discussion of general kinds of variants which can be

applied to many games (although there is no mention of progressive),

and other suggestions on how to create your own variants. Schmittberger

includes a number of his own inventions, as well as games by other

leading inventors such as Sid Sackson, Robert Abbott, and Christiaan

Freeling. Minor flaws are the lack of a bibliography or

suggested reading list (a few books are mentioned in the text), and a

somewhat haphazard layout. It's an extremely rich source of both

ready-to-play games, and ideas for inventors and tinkerers; every game

player and inventor should have a copy. Unfortunately, it

seems to now be out of print, but it's not hard to find inexpensive

used copies.

Go

Introductory Books

Baker, Karl -- The Way To Go, 1986, American Go Association, 46 pp., pamphlet

Bozulich, Richard -- The Second Book of Go, What You Need To Know After

You've Learned The Rules, 1987, Ishi Press, 184 pp., paperback, ISBN

4-87187-031-1,

Bradley, Milton N. -- The Beginner's Guide To The Game of Go, 1991, self-published, 203 pp., spiral bound

Chikun, Cho -- The Magic of Go, 1988, Ishi Press, 174 pp., paperback, ISBN 4-87187-041-1

Davies, James, and Richard Bozulich -- An Introduction to Go, 1984, Ishi Press, 92 pp., paperback

Davies, James, and Richard Bozulich -- The Rules Of Go, 1986, Ishi Press, 44 pp., paperback

Fairbairn, John -- Invitation To Go, 1977, 2004, Dover, 85 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-486-43356-0, $4.95

Iwamoto, Kaoru -- Go For Beginners, 1972, Ishi Press, 1986, Pantheon, 149 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-394-73331-2, $2.45

Kambayashi, Haruko -- Go Game For Beginners, 1964, Japan Publications Trading Company, 62 pp., paperback

Korschelt, Oscar, translated and edited by Samuel P. King and George G.

Lackie -- The Theory & Practice of Go, 1965, Tuttle, 269 pp.,

hardback, ISBN 0-8048-0572-5, $10.95, paperback, ISBN 0-8048-1660-3,

$3.75

Lasker, Edward -- Go and Go-Moku, The Oriental Board Games And Their

American Versions, 1934, Alfred A. Knopf, 214 pp., hardback; Second

Revised Edition, 1960, Dover, 215 pp., paperback, ISBN 486-20613-0,

$2.00

Almost the entire book covers Go; Go-moku is covered on pp. 205-213.

Pritchard, D.B. -- Go, A Guide To The Game, 1973, Stackpole, 216 pp., hardback, ISBN 0-8117-0740-7,

Soo-hyun, Jeong [8-dan], and Janice Kim [1-dan] -- Learn To Play Go,

Volume II: The Way Of The Moving Horse, 1995, Good Move Press, 164 pp.,

paperback, ISBN 0-9644796-2-1, $14.95

Shotwell, Peter -- Go! More Than A Game, 2003, Tuttle, 188 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-8048-3475-X, $14.95

Smith, Arthur -- The Game of Go, The National Game of Japan, 1908

(Moffat, Yard, and Co.), 1956, 1974 (23rd printing), Tuttle, 224 pp.,

paperback, ISBN 0-8048-0202-5, $3.75

Takagawa, Shukaku [9-dan] -- Go!, 1982, Sabaki Go Company, 249 pp., paperback

Reprinting of two books from the Nihon Kiin, in one volume: How To Play Go, 1956, and The Vital Points of Go, 1958

Elementary Go Series

Ishigure, Ikuro [8-dan] -- In The Beginning (Elementary Go Series, Vol. 1), 1973, Ishi Press, 152 pp., paperback

Kosugi, Kiyoshi [5-dan], and James Davies -- 38 Basic Joseki

(Elementary Go Series, Vol. 2), 1973, Ishi Press, 244 pp., paperback,

$4.50

Opening patterns of play.

Davies, James -- Tesuji (Elementary Go Series, Vol. 3), 1975, Ishi Press, 200 pp., paperback

Davies, James -- Life and Death (Elementary Go Series, Vol. 4), 1975, Ishi Press, 157 pp., paperback

Ishida, Akira [8-dan], and Davies, James -- Attack and Defense

(Elementary Go Series, Vol. 5), 1980, Ishi Press, 251 pp., paperback

Ogawa, Tomoko [4-dan], and Davies, James -- The Endgame (Elementary Go Series, Vol. 6), 1976, Ishi Press, 211 pp., paperback

General Strategy

Chikun, Cho -- Positional Judgment, High Speed Game Analysis, 1989, Ishi Press, 184 pp., paperback, ISBN 4-87187-045-6

Fujisawa, Shuko [9-dan] -- Reducing Territorial Frameworks, 1986, Ishi Press, 200 pp., paperback

Haruyama, Isamu [7-dan], and Nahagara, Yoshiaki [4-dan] -- Basic Techniques of Go, 1969, Ishi Press, 170 pp., paperback

Ishida, Yoshio [9-dan] -- All About Thickness, Understanding Moyo and

Influence, 1990, Ishi Press, 194 pp., paperback, ISBN 4-07187-034-0

The first Ishi Press book with two-color diagrams, using notes

in red to illustrate important points in most of the large diagrams.

Kajiwara, Takeo -- The Direction of Play, 1970, 1979, Ishi Press, 248 pp., paperback

Miyamoto, Naoki [9-dan], translated by James Davies -- The Breakthrough to Shodan, 1976, 159 pp., paperback

Nahagara, Yoshiaki [5-dan], with Richard Bozulich -- Strategic Concepts of Go, 1972, Ishi Press, 137 pp., paperback

Nahagara, Yoshiaki [6-dan], with Richard Bozulich -- Handicap Go

(Elementary Go Series, Vol. 7), 1982, Ishi Press, 199 pp., paperback,

ISBN 4-07187-016-2

Nihon Kiin -- A Compendium of Trick Plays, 1995, Yutopian Enterprises, 220 pp., paperback, ISBN 0-9641847-1-0, $14.95

Sakata Eio [9-dan] -- The Middle Game of Go, 1971, Ishi Press, 146 pp., paperback

Segoe, Kensaku, translated by John Bauer -- Go Proverbs Illustrated, 1960, Japanese Go Association

Yoshinori, Kano [9-dan] -- Graded Go Problems For Beginners, Volume 1,

Introductory Problems, 30-kyu to 25-kyu, 1985, Ishi Press, 226 pp.,

paperback, ISBN 4-8182-0228-2

Yoshinori, Kano [9-dan] -- Graded Go Problems For Beginners, Volume 2,

Elementary Problems, 25-kyu to 20-kyu, 1985, Ishi Press, 250 pp.,

paperback, ISBN 4-8182-0229-0

Yoshinori, Kano [9-dan] -- Graded Go Problems For Beginners, Volume 4,

Intermediate Problems, 20-kyu to 15-kyu, 1987, Ishi Press, 201 pp.,

paperback, ISBN 4-8182-0230-4

Yoshinori, Kano [9-dan] -- Graded Go Problems For Beginners, Volume 4,

Advanced Problems, 1990, Ishi Press, 199 pp., paperback, ISBN

4-8182-0231-2

The Opening Game and Joseki

Chikun, Cho [9-dan] -- The 3-3 Point, Modern Opening Strategy, 1991, Ishi Press, 214 pp., paperback, ISBN 4-87187-044-8

Hideo, Otake [9-dan] -- Opening Theory Made Easy, Twenty Strategic

Principles to Improve Your Opening Game, 1992, Ishi Press, paperback,

ISBN 4-07187-036-7

Ishida, Yoshio -- Dictionary of Basic Joseki, Volume 1, The 3-4 Point, 1977, Ishi Press, 266 pp., paperback

Ishida, Yoshio -- Dictionary of Basic Joseki, Volume 2, The 3-4 Point

(cont.), The 5-3 Point, 1977, Ishi Press, 304 pp., paperback

Ishida, Yoshio -- Dictionary of Basic Joseki, Volume 3, The 5-4 Point,

The Star Point, The 3-3 Point, 1977, Ishi Press, 264 pp., paperback

Encyclopedia of go openings.

Kato, Masao [9-dan] -- The Chinese Opening, The Sure-Win Strategy, 1989, Ishi Press, 146 pp., paperback, ISBN 4-07187-033-2

Takagawa, Shukaku [Honorary Honinbo] -- The Power of The Star Point,

The Sanren-Sei Opening, 1988, Ishi Press, 134 pp., paperback

Mathematics

Berlekamp, Elwyn, and David Wolfe -- Mathematical Go, Chilling Gets The

Last Point, 1994, A.K. Peters, 235 pp., hardback, ISBN 1-56881-032-6

Essays

Nakayama, Noriyuki -- The Treasure Chest Enigma, A Go Miscellany, 1984, Ishi Press, 191 pp, hardback

Magazines

Abstract Games -- edited by Kerry Hanscomb, published by C&K Publishing (formerly Carpe Diem), published irregularly

One of the best game magazines ever, devoted (mostly) to

abstract games, with in depth articles on many games by some of the

world's top experts. It ran as a print magazine for its

first 16 issues (from Spring 2000 to Winter 2003), beautifully

illustrated in both color and monochrome. It returned as an

online magazine with Issue 17 in Autumn 2019, and is currently up to

issue 24. The entire run of the magazine is available online in

PDF format. Most of the games covered are lesser known,

including many newly published ones, but there are articles on some of

the classic games like Amazons, Hex, Lines of Action, and many chess

variants.

Eteroscacco -- quarterly bulletin of AISE, Italian, 32+ pp.

AISE (Associazione Italiana Scacchi Eterodossi), formed in the mid-1970's by

Alessandro Castelli, eventully emerged as something of an Italian

counterpart of NOST, although it did not cover orthodox chess at all

and was more heavily oriented toward chess variants than other abstract

board games. But it did conduct tournaments in (and publish

articles on), some of the major abstracts.

Nost-Algia -- monthly bulletin of NOST (Knights of the Square Table) -- 1960-199? (abbreviated NA)

NOST was formed in 1960 by Bob Lauzon and Jim France. Originally a

postal chess club, it branched out into chess variants as well as many

other games. It conducted tournaments and matches in a large

number of games, including many NCG (Non-Chess Games), and held an

annual convention (NOSTvention, or NV). Eventually Nost-Algia became a

bimonthly 28 page magazine, with several pages devoted to NCG (many

of them abstract board games, including several checker variants, plus

Amazons, Cathedral, Delta, Fanorona, Go, Lines of Action, Reversi, etc.).

Most recently edited on November 5, 2024.

This article is copyright ©2024 by Michael Keller. All rights reserved.